Martin Luther's 95 theses

Quick links on this page

Peasants Revolt 1381

Martin Luther 1517

Act of Supremacy 1534

Bottom of Page 1539

|

Alternative and Non-Conformist Religion

Before the Reformation

|

1257

|

Even within the early church there was dissent which sometimes led to violence. By 1257 the town of Bury St Edmunds was firmly under the sway of the Abbot of St Edmunds, the head of the established Benedictine Abbey and Monastery in the town

The Bury Chronicle recorded that on 22nd June the Friars Minor entered the town of St Edmund's by stealth. The Franciscans celebrated mass in an audible voice in the presence of all comers, but unknown to the convent. The local Franciscan Friars Minor were saying mass in the home of a local supporter, Sir Roger de Harbridge just by the east side of the Northgate. Meanwhile, when Sir Roger and the Friars sat down to dinner, the Abbey's supporters were demolishing the Friars' Oratory and buildings in an attempt to drive them out.

The friars had considerable support. King Henry III, Gilbert de Clare and many burgesses wanted to help them break the monopoly of the abbey within the banleuca.

However, these differences were not so much about religious doctrine as they were over territorial rights.

|

|

1265

|

The dispute between the Benedictine Abbey and the Fanciscan Friars dragged on for over 5 years.

By 1265 the Abbey finally gave the Franciscans land for a permanent home at Babwell just outside the Banleuca where today's Priory Hotel stands.

However, the Grey Friars still could not enter town without the abbot's permission, and thus were excluded from an easy involvement in civic life. It is not surprising that they tended to side with the townspeople in their disputes with the abbey. In turn they won many friends in town.

They were not the only religious dissidents against the abbey. The rectors with livings in the town, and the so-called secular priests, were treated as second class churchmen by the monks and in turn they also sided with town against abbey. This religious backing was to become important to the burgesses in their growing struggles with the great abbey.

|

|

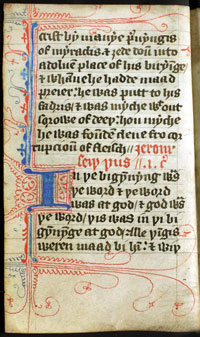

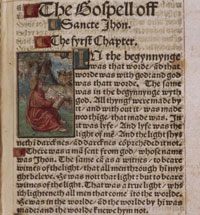

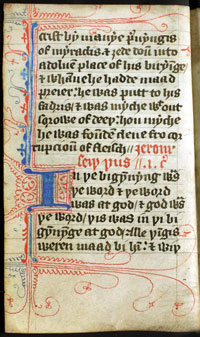

Wycliffe's Bible Gospel of St John

|

|

1370

|

John Wycliffe lived from 1329 to 1384. In 1360 he was forced to leave his post as Master of Balliol College at Oxford for preaching against clerical wealth and privilege, papal authority, confession, transubstantiation, and monasticism.

Wycliffe continued to preach the confiscation of the wealth of the monasteries, by now generally held to be more interested in money making than in religion. John of Gaunt and other nobles supported him because they feared and envied the wealth and power of the church. Wycliffe's followers, known as the Lollards, produced a Middle English version of the bible in the 1390's and in general attacked monastic life and church ritual.

Thus the bible known as Wycliffe's Bible was not produced until after his death.

Lollard preachers were well received by lesser gentry, yeoman farmers and particularly by the weavers of East Anglia over the rest of the century.

|

|

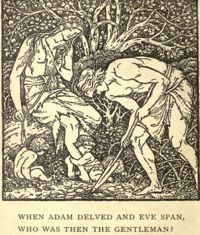

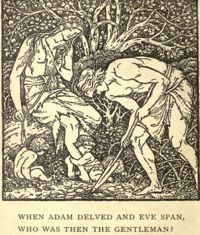

The rebel question |

|

1381

|

This was the time of the so-called Peasants' Revolt.

Two armies from Kent and Essex, led by Wat Tyler and John Ball, marched on London, entering it unopposed on 12th June. When the rebels arrived in Blackheath on June 12, the Lollard priest, John Ball, preached a sermon including the famous question "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?". In other words he was using the bible to question the established class system of the time.

Ball was a vagrant priest of a type who always seemed to crop up in these revolts of the time. These clerics were outside the church establishment, and were developing their own theology. Gradually this became known as Lollardy.

|

|

1382

|

After the Christmas recess, Parliament resumed its sitting on January 27th until February 25th, 1382. In an attempt to suppress the ideas raised by John Ball which had helped to provoke the uprising in 1381, an act of parliament was passed to outlaw heretical preachers and their teachings. Such ideas were described as destructive of the laws and the estate of holy church.

So strong was popular support for Lollards that Parliament eventually forced the king to withdraw the law passed to help the arrest of heretics.

|

|

1401

|

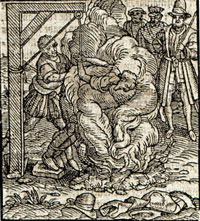

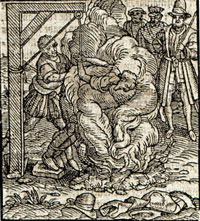

Despite widespread support for the Lollards, a law was passed ordering the burning of obstinate heretics. A number of executions were carried out. Henry IV's statute was called "De Heretico Comburendo".

According to Nate Sullivan at the website www.Study.com,

"The Lollards were a group of anti-clerical English Christians who lived between the late 1300s and the early 1500s. The Lollards were followers of John Wycliffe, the Oxford University theologian and Christian Reformer who translated the Bible into vernacular English. The Lollards had profound disagreements with the Catholic Church. They were critical of the Pope and the hierarchical structure of Church authority. The Lollards emphasized personal piety, humility, and simplicity in their relationship to God, rather than formality. The term 'Lollard' was a derogatory term given to the group by the established Church. The exact origin of the term remains uncertain, but it is believed by many etymologists to have come from the Dutch word 'lollaerd,' meaning 'mumbler.' By the mid-1400s, the word had essentially become synonymous with 'heretic.'"

|

|

1407

|

The Lollard Bible was banned. It had been produced in English in the 1390's. Lollard ideas against the established religion continued to get grass roots support, as well as some high ranking assistance.

|

|

1410

|

By the early 15th century, stern measures were undertaken by Church and state which drove Lollardy underground. One such measure was the 1410 burning at the stake of John Badby, a layman and craftsman who refused to renounce his Lollardy. He was the first layman to suffer capital punishment in England for the crime of heresy.

|

|

John Oldcastle executed

|

|

1414

|

John Oldcastle was brought to trial in 1413 after evidence of his Lollard beliefs was uncovered. Oldcastle escaped from the Tower of London and organized an insurrection, which included an attempted kidnapping of the king. The rebellion failed, and Oldcastle was executed by burning in 1417. Oldcastle's revolt made Lollardy seem even more threatening to the state, and persecution of Lollards became more severe.

With these events any support of the well to do fell away. However, the sect's following amongst the weavers was to survive for many years driven underground. Support in Suffolk was mainly in the Waveney Valley, such as Beccles and Bungay. Lollards pre-dated Protestants in nearly all of their key beliefs.

|

|

1431

|

In Suffolk, Lollards were persecuted for opposing many Catholic religious practices. From 1428 to 1431 there were many prosecutions and two executions, particularly around Beccles and Bungay.

A hundred years later Martin Luther would repeat many of the Lollard teachings.

|

|

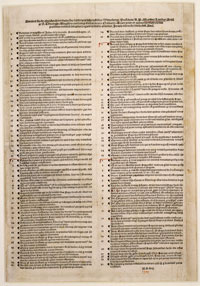

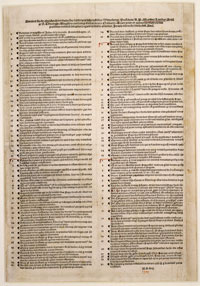

Poster of Luther's 95 theses

|

|

1517

|

In Germany Martin Luther sparked off the Protestant movement. By the 1520's some English intellectuals would follow his ideas.

|

|

Cardinal Wolsey

|

|

1519

|

In parallel to the rise of Martin Luther's ideas, Cardinal Wolsey first proposed reform of the monasteries when he became Cardinal Legate in 1515. Wolsey was born in Ipswich and had a brilliant career at Oxford before becoming Chaplain to Henry VIII and then his Lord Chancellor in 1515.

|

|

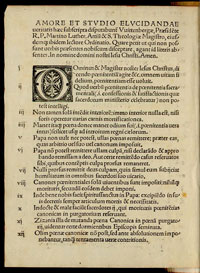

Page from Tyndale's New Testament

|

|

1526

|

In 1526 William Tyndale published a translation of the New Testament in English, which was immediately denounced by the English Bishops. By now he had been forced to work abroad, and his books were printed in Worms and Antwerp and smuggled into England. One of Tyndale's supporters was Humphrey Monmouth, a London wool merchant. Monmouth dealt in Suffolk cloth, and seems to have brought back some of Tyndale's books from the continent and introduced them to Protestant leaning Suffolk clothiers. He certainly showed some to Dr Stockhouse, the rector of Lavenham, in 1528. Stockhouse found no fault with them, and must have had Protestant leanings himself. Nevertheless, these books were illegal, and Monmouth would be imprisoned for distributing them.

Thomas Turner of Haverhill was very active in the apprehension and examination of non-conformists in that area. In 1527 eight Lollards were discovered at Steeple Bumpstead and were tried for heresy.

|

|

1534

|

The King married his second wife, Ann Boleyn, having initiated a decisive break with the Church of Rome in order to do so. They had a daughter who would become Elizabeth I, although the elder daughter Mary had precedence to the throne. The Succession Act of 1534 stated that Ann Boleyn's children would succeed as monarchs.

The Act of Supremacy of November 3rd, 1534, changed the whole constitution of the country. Previously the Pope and the Church of Rome had wielded tremendous power through its Abbots and Archbishops, who sat in Parliament as Lords Spiritual. This power was backed by the economic power represented by vast church landholdings and rentals, feudal dues, local courts, and the moral sway over the congregations. Henry VIII was announcing that from henceforward, all this power would come under his personal control.

To ensure that people accepted this situation, The Treasons Act was also passed in 1534. It provided that to disavow the Act of Supremacy and to deprive the king of his "dignity, title, or name" was to be considered treason.

Ironically, Henry had been declared "Defender of the Faith" (Fidei defensor) in 1521 by Pope Leo X for his pamphlet accusing Martin Luther of heresy. (Parliament later conferred this title upon Henry in 1544.)

|

|

1535

|

Following the Act of Supremacy came the Treason Act, which gave the death penalty to anyone who denied the king's rights in any way or who called him heretic, schismatic or tyrant. Under this act, Sir Thomas More, Cardinal John Fisher, and eight others were executed for refusing to accept royal supremacy in religion. Clearly the religious houses were going to be a thorn in the king's side over these matters.

|

|

1536

|

In 1536, the first complete bible to be published in English was produced, in a translation by Miles Coverdale. It was known as Coverdale's Bible, and although it was revolutionary, it was to be largely displaced in 1539 by the Great Bible. Many churchmen, such as Sir Thomas More , had been against a bible in English, as it would allow the common people to form their own opinions from the original text. But the pressure from the people, and from the new printing presses, was unstoppable. Even the King was now sympathetic to the use of English.

|

|

1538

|

During 1538 the Second Royal Injunction reflected Lutheran protestant ideas by forbidding placing candles before images and other superstitious practices. English bibles were now officially encouraged. The clergy were told to teach the Lords Prayer, the Creed and the Ten Commandments in English. Every parson had to provide an English Bible in his church with free access to anyone who wished to read it.

|

|

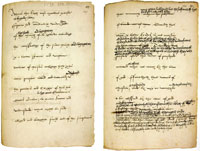

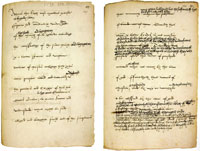

Draft of Six articles

|

|

1539

|

In April 1539 the Great Bible was published in English. The Church was being reformed, while its possessions were being seized. However, the King himself was less keen on carrying forward further Protestant ideas. He was happy to be head of his new church, and to get his hands on the wealth of the monasteries, but religious reform was of less interest to him.

In June 1539 Henry issued his Act of Six Articles which effectively halted any further official extension of Protestant ideas. Formally titled "An Act Abolishing Diversity in Opinions", the Act of Six Articles reinforced existing heresy laws and reasserted traditional Catholic doctrine as the basis of faith for the English Church.

The six controversial doctrinal questions were considered by the House of Lords:

- whether the Eucharist could be the true body of Christ without transubstantiation,

- whether it needed to be given to the laity under both kinds,

- whether vows of chastity needed to be observed as part of divine law,

- whether clerical celibacy should be compulsory,

- whether private masses were required by divine law,

- whether auricular confession (that is, confession to a priest) was necessary as part of divine law?

King Henry VIII was closely associated with these articles. The attached draft is amended by him in his own handwriting.

From now on Henry VIII would support little further Protestantisation of his Church. One of the architects of the Six Articles was Bishop Stephen Gardiner who now seemed to be reverting to Catholic ideals. The Six Articles led to the resignation of Bishops Latimer and Shaxton and the persecution of the Protestant party. These laws, also known as the Bloody Statute, have sometimes been attributed solely to Gardiner, who was born in Bury St Edmunds, and educated at Cambridge. The penalty for denying transubstantiation was to be burnt at the stake, and the other articles had hanging or life imprisonment as penalties. Married priests had until 12 July to put away their wives, which was likely a concession granted to give Archbishop Cranmer time to move his wife and children abroad.

(These requirements would remain in force until 1547 under Edward VI.)

|

|

|

Quick links on this page

Top of Page 1257

Peasants Revolt 1381

Martin Luther 1517

Act of Supremacy 1534

|

|

Next

|

The Reformation of the English Church started with Henry VIII making himself head of it in place of the Pope. This led to a wave of resistance culminating in a brief return to Catholic Rome, and reversion to a form of Protestantism.

|

Prepared for the St Edmundsbury Local History Project

by David Addy, July 17th, 2020

|