Martin Luther's 95 theses

Quick links on this page

Queens Jane & Mary 1553

Protestant martyrs 1555

Queen Elizabeth I 1559

Royal Progress Suffolk 1578

Spanish Armada 1588

James I 1603

Civil War 1642

Bottom of Page 1645

|

Alternative and Non-Conformist Religion

After the Reformation

|

1547

|

Henry VIII died on January 28th 1547 at the age of 56, having reigned over 37 years. His requiem mass was led by Stephen Gardiner, the Bury born Bishop of Winchester. He left only one young son, King Edward VI, who became king aged 8 years. King Henry's break with the Roman Church and the dissolution of the monastic system had been the greatest social upheaval in hundreds of years. Henry VIII had taken over monastic lands and made some Reformation of the Church, but he feared to go too far to avoid civil unrest.

Under the new king, Henry's policies were reversed and the Second Reformation of the English Church began. First came The chantries Act of 1547 that dissolved all the secular colleges and religious guilds, as well as the Chantries. This was important for Bury as it possessed one of England's 140 secular Colleges. This was the College of Jesus founded by Jankyn Smythe. It would close in 1548. A similar college at Stoke by Clare closed in that same year, despite the fact that Matthew Parker, Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University, was its Master.

Also to close, and its endowment properties sold off, was the Chantry College of Denston, founded in 1475 by John Denston, and located within St Nicholas' Church at Denston. As this was also the parish church, the church itself survived the confiscations.

It is possible that there was a College of secular priests at Chevington, but there seem to be no records. College Farm and College Green still exist in the village. The church records for 1595 record a "Henry Paman of the college, deceased."

Injunctions of July 1547 ordered the destruction of all shrines, paintings and pictures of saints. The Six Articles of 1539 were repealed.

These Protestant Reforms were opposed by the Bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner. He had played perhaps the biggest part in drawing up Henry VIII's Six Articles, and he remained true to their principles. Gardiner, who was born in Bury, fell out of favour, and was thrown into prison. At first he was in Fleet Prison, but following an enquiry, was moved into the Tower of London, where he stayed throughout the reign of Edward VI. In 1555 he was formally removed from the office of Bishop of Winchester.

|

|

1548

|

At church, the Reformation continued. In February 1548 the Privy Council ordered the removal of all religious images from churches.

|

|

1549

|

There was an increase in the reformation of church practices. All images and shrines were now banned as were processions and elaborate church equipment. Services were to be in English. Another Act allowed priests to marry, and in Suffolk probably about a quarter eventually married.

In Cornwall there had been several tense years when the religious reformation was pressed home too harshly. A rumour in 1549 that a new English prayer book was to brought in at Whitsun, caused a rebel camp to be set up.

The First Act of Uniformity was duly passed in 1549 and made the first English language prayer book the required basis for church services. This was the Book of Common Prayer, a first national imprint of Protestantism. The rebels laid siege to Exeter in July and Lord Somerset sent a force to contain the situation. The situation was looking grim when another major rebellion appeared in East Anglia.

The East Anglian Uprising, known as Kett's Rebellion, started in Wymondham in July when enclosure fences were torn down. In this rebellion there seems to have been much less emphasis upon religious reform as a major grievance, unlike in the West Country.

Unlike the Cornish rebels, the East Anglians favoured the new English Prayer Book and adopted its use.

|

|

1550

|

King Edward VI was a strong Protestant, and was also responsible for the destruction of many books surviving from monastic days on the grounds that they contained superstitious images and ideas from the Papist era. In 1550 Injunctions were passed which even ordered the removal of alters from Parish Churches. Simple tables could replace them, provided they were not on the same positions.

|

|

1552

|

Parliament passed the Second Act of Uniformity. Church attendance was made compulsory on Sundays.A second new Prayer Book was introduced. Church vestments were already banned and alters had been replaced by tables in the previous year. The ancient Mass was effectively now replaced by a Protestant Holy Communion.

|

|

1553

|

By 1553 the 15 year old King Edward VI was dying of TB. He was an enthusiastic Protestant and, on his deathbed, disinherited his Catholic sister Mary to avoid his reforms being reversed. The legality of this act of disinheritance was questionable, and many people thought it the result of a plot.

The English church was totally reformed by now, both in the destruction of statues and decorations, and in the forms of worship. In 1553 Thomas Cranmer issued his Forty Two Articles of Religion which gave the English Church its final Protestant Theology. King Edward VI died on July 8th.

It was said that John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, was behind the plan to replace Mary by Lady Jane Grey. Some people supported this move because Lady Jane was a Protestant.

On 11th July the Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, Sir Thomas Cornwallis, with other local nobles, joined Ipswich Town Council in declaring Lady Jane Grey, the Queen of England. The people of the town were much less enthusiastic, and there were some disturbances. John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, was not popular in East Anglia, having been involved in the bloody suppression of Kett's protest camp in 1549, when he was the Earl of Warwick.

Mary Tudor was the rightful Queen in the eyes of much of the country, and poor manipulated Queen Jane was to reign for only nine days.

|

|

Queen Mary

|

|

blank |

Mary was proclaimed Queen on July 19th 1553 by the Privy Council in London. With Northumberland's army out of London they could see that she had widespread support, and admitted they had been in error. The Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the city proclaimed Mary the true Queen along with the Duke of Arundel, by public proclamation. They now put out a reward for the capture of Northumberland. Northumberland's army was now refusing to proceed past St Edmundsbury because of the size of the army waiting for them at Framlingham. Many were deserting Queen Jane's cause.

The Duke of Suffolk was now vigorously turning against Jane, despite the fact that she was his daughter, and even tore down her banner with his own hands, said she was no longer queen, and ordered his men to disarm.

The population of London went wild with joy at this news.

On 20th July many of the Council, including Arundel, had ridden to Framlingham to pledge allegiance to Mary, and to beg for forgiveness for ever supporting Jane. Sir William Waldegrave was there from Bury in her support, and even protestants like Edward Withipoll of Ipswich were now in Framlingham to pay court. By now, Northumberland's army had reached Bury, and the Framlingham army was mustered to attack them. In the event Northumberland retreated, and a smaller band went in pursuit of him and any supporters they could find.

Queen Mary would reign for only five years until 17th November 1558. She came to the throne on a wave of popular support, but would leave it almost universally despised. She now set about a Catholic revival, while promising freedom of worship.

The First Statute of Repeal was passed by Parliament which repealed all of Edward VI's protestant legislation.

Within days the churches in the City of London had alters and crucifixes installed. Nicholas Ridley was thrown into the Tower, and Stephen Gardiner replaced John Ponet as Bishop of Winchester. Stephen Gardiner also became her Lord Chancellor. He was a devout Catholic, and was the son of John Gardiner, a Bury St Edmunds Clothmaker. Like Nicholas Bacon, also of Bury origins, he probably helped the town by minimising the impact of the dissolution of the guilds, and helped the feoffees.

Many prominent protestants now left the country, all within a matter of three weeks. In a few more weeks many prominent men throughout the land were replaced in public offices by Catholics. Queen Mary replaced all of the religious provisions of both Henry VII and Edward VI's reign. Churches were ordered to re-equip for Catholic worship and the old services reinstated.

By November, Mary wanted to marry Philip of Spain amidst general public protest.

|

|

1554

|

In January, Sir Thomas Wyatt raised an army of 4,000 men in Kent in an attempt to stop the Spanish marriage, and in protest against the removal of the reformed faith.

Wyatt and many of his supporters were arrested. Within a few weeks Wyatt's protest had failed.

Mary was now convinced that a crack down was needed, and hundreds of Wyatt's followers were hanged. In February Lady Jane Grey was executed along with her husband, Guilford Dudley, and the Duke of Suffolk, Henry Grey, her father.

Queen Mary issued injunctions that removed the newly married priests from office.

In August Queen Mary married Philip, "the Prudent", of Spain in Winchester Cathedral.

After her marriage the Heresy Laws were revived, and the Second Statute of Repeal aimed to undo Henry VIII's anti-papal legislation. The country was to return to the ways of 1529, but it was too late to undo the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

|

|

1555

|

By 1555 the second Parliament under Mary had passed laws which restored the Roman Catholic Church officially in England. All the laws which had been passed to remove the authority of the Pope were now repealed. But of more significance was the decision to restore the medieval penalties for so-called heretics who continued to oppose these changes.

Queen Mary's Lord Chancellor was Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and a Bury man who helped the town retain or re-acquire monastic lands seized directly by the crown. Gardiner had overseen the laws which re-introduced burning at the stake for protestants.

This change was to result in Queen Mary being remembered as Bloody Mary for her persecution of Protestants. The burning of heretic Protestants now got underway. A church court could pass this sentence, and the victim was then handed to civil authorities to carry out the sentence.

|

|

First Suffolk Martyr

|

|

blank |

In February Dr Rowland Taylor, the Dean of Hadleigh, was burned to death on Aldham Common. He was the first of the Marian Martys, (as they are known), to die in Suffolk. Nationally, over 300 people would die in this manner before Queen Mary herself died. Twelve were martyred in Bury, and their memorial stands in the Great Churchyard. About 30 Suffolk people were martyred in total.

The martyrs were not just church officials, or prominent citizens. For example, James Abbes, a shoemaker from Stoke by Nayland, was burned at Bury in August, 1555.

In September 1555, Thomas Cobbe, a butcher from Haverhill, suffered martyrdom at the stake at Thetford for his Protestant faith. He had denied transubstantiation and said that Baptism was not a sacrament.

|

|

1556

|

In February 1556, Latimer and Ridley were burned at the stake in Oxford. Thomas Cranmer followed them shortly afterwards.

Women could also suffer this fate. For example at Ipswich, in February 1556, Joan Trunchfield, a shoemaker's wife, and Anne Potton, a beer maker's wife, were both burned to death on the Cornhill for refusing to renounce the Protestant religion.

Philip of Spain now became King Philip of Spain when Charles V abdicated.

|

|

1557

|

Despite war and hardship from poor harvests, the burning of Protestants continued. At St Edmundsbury, three people were burned in June, 1557. They were Roger Barnard, a labourer from Framsden, Adam Foster, a tailor from Mendlesham, and Robert Lawson, a linen weaver from Bedfield.

In November, Thomas Spurdance, described as a royal servant, from Crowfield, was also burned at Bury.

|

|

1558

|

In August 1558 there were more burnings at Bury St Edmunds. All four of the victims were from Stoke by Nayland, Robert Miles, a shearman, Alexander Lane, a wheelwright, John Cooke, the sawyer, and James Ashley.

Three more Protestants were killed at Bury in November, only days before Bloody Mary herself was to die in her bed. They were Philip Umfreye, a tailor from Onehouse, and from Stradishall, John Davye, a shearman, and Henry Davye, a carpenter.

It is noticeable that nobody from the town of Bury itself was burned as a Protestant heretic. While Hadleigh had a strong Protestant movement, as had Ipswich, it was the Stour Valley and central Suffolk where anti-Catholic feeling was strongest at this time. Haverhill and Stradishall had their martyrs while much larger Bury did not.

Parliament had always refused to name Philip as a successor King of England, and so in November, as Mary lay dying, she named Elizabeth as her successor. Philip, now King of Flanders, as well as Spain, tried to maintain his hold on England.

Mary had come to the throne on a wave of popular support, but she died hated, on 17th November. Vast cheering crowds greeted Elizabeth to London. Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne and reigned for forty-four years.

|

|

1559

|

Queen Elizabeth immediately began to once again dismantle the trappings of catholicism in the churches and re-introduce protestant forms of service.

The Act of Supremacy of 1559 once again made the monarch head of the English church. This has been called the Third Reformation of the English church, counting Henry's as the first and Edward VI's as the second. The Queen made herself Supreme Governor of the Church of England and decreed that her coat of arms should be placed in every church.

The Act of Uniformity authorised a new English Prayer Book, and levied a shilling fine on anyone not attending Sunday church of the new Protestant type. This prayer book was not quite so strict about the doctrine of transubstantiation and a concession was made which allowed crucifixes and some furnishings in church. Some vestments could be worn by priests and the sign of the cross could be made at Baptism. This was protestantism with enough of the old ways retained to appease those who missed the old religion. While this may have helped reconcile the ordinary folk to the new church, it satisfied neither the strong Catholic or the new Puritans.

|

|

1561

|

By 1561 Queen Elizabeth had again fully changed the appearance of English churches and services back to protestantism. Many noble families were caught up in the changes of the last twenty years, coming in and out of favour as the state religion changed. A number of important Suffolk families kept the Roman Catholic faith, the most notable being the Howards who were Dukes of Norfolk. Others were the Bedingfields, the Sulyards of Haughley Park and the Rokewoods of Euston and Stanningfield. Sir Thomas Cornwallis had been controller of the household to Queen Mary, but now retired to Brome in Suffolk.

At Hengrave Hall, Margaret Kytson died, to be succeeded by her son, Thomas Kytson, the younger. Thomas was a friend of the Duke of Norfolk, and at this time also came under suspicion for this association.

On the other hand there were even more families of a Puritan persuasion, a faith that continued to grow. At Ipswich the Queen was offended when the extreme protestant clergy refused to wear the surplice, which she had just re-introduced, as part of her compromise reforms.

|

|

1562

|

Part of Queen Elizabeth's church reforms included the licensing of preachers. Only those ordained ministers trusted to preach the official doctrine would be given a license. Any minister who was unlicensed could only read out a pre-written sermon. A selection of acceptable sermons was published in 1562, entitled "Certain Sermons or Homilies, appointed to be read in Churches." This book was reprinted many times and was still in use in 1683, when it was re-issued under Charles II.

|

|

1563

|

The first Witchcraft Act came into force in England. English law now accepted witchcraft as a fact, and it was made a crime to be found guilty of witchcraft. The Witchcraft Acts were not abolished until 1763.

|

|

1565

|

Bury St Edmunds was divided into the two parishes of St Mary's and St James'. Each parish had a minister, who was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Norwich, and a preacher, chosen by the congregation. In Bury at this time the congregations also claimed the right to appoint their own minister, which could become a point of conflict with the bishop. In 1565, one of the town preachers was George Withers, a Protestant whose views were more reformist than the English Reformation allowed. Withers caused controversy when he refused to wear a cornered clerical cap.

|

|

1568

|

Sir Edward Coke reported that three Suffolk Gentlemen refused to attend church. These Catholic recusants, as they were called, were Messrs. Cornwallis of Brome, Beddingfield of Denham, and Silyarde of Haughley.

|

|

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

|

|

1570

|

Religious questions were the main intellectual topic of the day. This is the second edition of John Foxe's Book of Martyrs which was printed in 1570 by Suffolk man, John Daye. (The first edition came out in 1563.) This particular volume would be preserved in St James library and would be one of the largest volumes that the library possessed. Indeed, at this time it was the largest publishing project ever carried out. The 1570 edition was 2,300 pages long, with major corrections and additions to the first edition. It was so well received by the English church that it was to be placed in every church in the land, alongside the Bishops' Bible. It deeply offended Catholic sensibilities, and would become the main tract of anti-catholic feeling for decades afterwards.

Although it covered all the early martyrs, its intent was to concentrate upon the sufferings of English Protestants in the Tudor period under Queen Mary. This page shows the death of Roland Taylor, Rector of Hadleigh and Archdeacon of Bury, who was burnt to death at Hadleigh in 1555.

The Feoffees even felt it necessary to finance a Town Preacher in Bury, and Puritan ideas led to a rise in religious discussion groups, and the clergy were as likely to be criticised as anyone else, for not being Godly enough. These ideas would gain more and more ground to the middle of the next century.

The Pope, Pious V, increased the pressure on England by issuing a Bull which excommunicated and deposed Queen Elizabeth I. This declaration, "Regnans in Excelsis", in effect meant that the Pope declared war on England. After this event Catholicism was regarded as treason in England, and penalties against them were more rigidly enforced.

Those Catholics who had hitherto quietly attended church as non-communicants or schismatics, (meaning that they followed protestant worship but were catholic in their hearts), were now faced with either defying the Pope or joining the new church fully. Hard choices had to be made, both by Catholics, and by the Queen, who had a potential Fifth Column of recusants in her midst.

|

|

1572

|

The 4th Duke of Norfolk, of the Howard family, like his predecessors, had kept the Roman Catholic faith. In 1571 he had become involved in the plot to replace Queen Elizabeth by Mary, Queen of Scots. He was put in the Tower and executed in 1572. Up to this point he had held tremendous power in both Norfolk and Suffolk, appointing JP's and getting involved in nominating MP's as well. His execution gave other lesser gentry of Suffolk the freedom to get much more involved in public life in the county. The Duke of Suffolk had already lost much of his hold over Suffolk when the Liberty of Eye was returned to the Crown in 1538.

At the other end of the religious spectrum were the more extreme protestants. Both Catholics and extreme Protestants were out of favour with the established church and state because of their refusal to conform to the established modes of worship and thought. In 1572 the more Protestant elements in Bury St Edmunds brought in a new Town Preacher called John Handson. Handson quickly came to the attention of the establishment for refusing to wear a surplice, not just during normal services, but even during holy communion.

|

|

Coldham Hall

|

|

1574

|

Robert Rookwood built Coldham Hall at Stanningfield. Rookwood was a wealthy Roman Catholic, and there is a priest hole in the Hall. His son, Ambrose, would get involved in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

|

|

Matthew Parker

|

|

1575

|

In 1575 Archbishop Matthew Parker died and left his extremely important collection of monastic and religious documents to Corpus Christi College in Cambridge, including the Bury Bible, and other manuscripts from the Bury Abbey. It is also one of the finest collections of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts in the world, including Version A of the Anglo-Saxon chronicles.

Matthew Parker was born in Norwich on August 6th 1504 and came to Corpus as a student and was ordained in 1527. He became Chaplain to Ann Boleyn, and she got him appointed dean of the college of secular canons at Stoke-by-Clare in 1535. He became chaplain to Henry VIII in 1538, and was recommended to Corpus as its new Master by Henry in 1544. Under Queen Mary he retired from public life to Norfolk and was deprived of his livings, but when Queen Elizabeth came to the throne, he was reinstated. He was installed as Archbishop of Canterbury 13 months later at the age of 55, and held the post until his death. He now had to mediate between the Catholics and the extreme Protestants to find a middle way for the Church of England. Between 1563-1568 he produced the new official version of the Bible - the 'Bishop's Bible' which was the authorised version until the King James Bible in 1611. He also supervised the revision of Cranmer's 42 doctrinal articles to produce the definitive 39 Articles of Religion which defined the doctrine of the Church of England.

He also set about finding independent evidence of the origins of an independent Christian Church in England to justify the split from Rome.

|

|

1576

|

Chief Justice Wray wrote to Lord Burghley to complain that the Elizabethan church settlement was accepted everywhere except Norfolk and Suffolk. Although he complained that many were papists, he said that most of them were Puritans, although he called them "wilful and indiscreet precisians". There were some notable Catholics among the gentry, but there were far more radical protestants in Suffolk. The latter soon became better known by the name of Puritan.

One such man was John Copping, a local minister near Bury St Edmunds.

In 1576 he was brought before the bishop of Norwich's commissary, and committed to prison at Bury, where he was charged with maintaining the following opinions:

- “That unpreaching ministers were dumb dogs:

- That whoever kept saints' days were idolaters:

- That the queen, having sworn to keep God's law, and set forth his glory as appointed in the scriptures, but did not, lay perjured:

- That for six months he had refused to have his own child baptized, because he had determined that none should baptize it who did not preach;

- and that he would not admit a godfather or godmother on the occasion.”

John Copping would languish in jail for two years, be examined and condemned again for another five years, and eventually hanged.

|

|

Queen Elizabeth I

|

|

1578

|

Queen Elizabeth I had reigned for twenty years, and was in the habit of undertaking Royal Progresses through the kingdom. This kept her in touch with people and ideas, and allowed her to favour the compliant and snub the disaffected or fanatical adherents to religious views of which she disapproved. It was also her general policy to show herselves to her people, and to gain acceptance for her ideas by the force of her royal presence in their own towns.

At home, the major issue was the refusal of Catholics to accept the official Protestant religion. This issue was made more dangerous by the presence of Mary Queen of Scots under house arrest in Derbyshire. She could at any time become the focus of a Catholic uprising. East Anglia was prosperous and densely populated, and Norfolk and Suffolk retained a number of important Catholic families. Not only that, but the Bishop of Norwich at the time was Edmund Freake. Freake seemed to be happy to come down heavily upon the Puritans, who were too extreme for the state sponsored religion, but to be reluctant to move against Catholics, who were much more feared by the government.

Therefore it was decided that a Progress up to Norwich would force these issues into the open. In May the first ideas were being discussed at Court. In mid June, Thetford and Norwich were given official notice to expect the Queen in August.

A visit to Melford Hall lasted from Saturday evening of August 2nd until early morning on Tuesday, 5th August, 1578.

On Tuesday, the Queen journeyed northwards to Lawshall Hall, the home of Henry Drury , where she dined, but did not stay overnight.

Henry Drury was a Catholic, and although nothing happened while the Queen was at his home, he would later be arrested for his faith.

On 8th August, Lord Burghley wrote that the people of Bury were "very sound saving in some part affected with the brainsick heresy of the papistical Family of Love." The Family of Love was an heretical sect who believed that only they would be saved on the Day of Judgement, and had some following in the east of England. The 'Family' was outlawed in 1580.

|

|

Thomas Kytson 1573

|

|

blank |

At Bury she knighted Thomas Kytson the younger, of nearby Hengrave Hall. By now Kytson had persuaded the Queen that he supported her rule and her religious policies, having been previously under suspicion for Catholic extremism. Kytson had the advantage of being fabulously wealthy, but not being of noble birth, was glad to be rewarded for his promises to attend church and listen to orthodox sermons by being given his knighthood. Nevertheless, he provided generous hospitality to courtiers on the Progress.

The Queen had stayed an unusual length of time at Bury, and left that town on Saturday 9th August, heading for Mr Rookwood's house at Euston for the weekend. Edward Rookwood was a Catholic gentleman, and brother to Ambrose Rookwood of Coldham Hall in Stanningfield. This two day visit by the Queen turned out to be a disaster for Rookwood. Usually nothing untoward would happen while the Queen was on the premises, but Lord Chamberlain Sussex berated Rookwood for coming before the Queen and ordered him to leave his own house. The Spanish ambassador would later report that Rookwood had received the Queen with a crucifix around his neck. A search was made of the premises, ostensibly to look for a missing piece of the royal plate, but a statue of the Virgin Mary was discovered, hidden in a hayrick. It was brought to the Queen who ordered it burnt.

On the 15th August, the parishioners of St James, in Bury St Edmunds, sent a petition to Lord Burghley, on behalf of their town preacher, John Handson. According to J S Craig, (SIAH Vol 37, part 3, 1991), it is likely that Handson had been called before the royal council, when in Bury, and indicted to appear before the next assize to answer for the doctrinal views in his preaching. Handson was a more radical Protestant than some more conservative townsmen could accept. There were 63 signatures all testifying that Handson was a true and faithful subject, beset by enemies and false accusations. This letter seems to have gained Handson a reprieve from further official action against him, but he still had enemies in the town.

On 22nd August, the Council had examined several recusants at Norwich, handing out such judgements as they thought fit, including house arrest with local reliable Protestants where they would receive daily persuasion to convert from the Bishop or his man. Edward Rookwood had also been summoned up from Euston, and he was now imprisoned in Norwich Gaol, where he stayed until October. Only Rookwood and Robert Downes were actually held in Norwich Gaol.

On her progress back from Norwich, the Queen stayed at Hengrave Hall for three nights from August 27th. Sir Thomas Kitson had only been knighted when the Queen had been in Bury a few weeks earlier, but he was fabulously wealthy. The stay was a notable one, outdoing many others by its lavish hospitality and entertainments.

At Hengrave the Privy Council met three times, continuing to concentrate on the perceived Catholic threat. They considered a list of 34 names from Suffolk, interviewing a group of them.

Nine were sentenced to imprisonment for refusing to conform to the state religion. This was mostly a form of house arrest, in the house of other more reliable citizens. Henry Drury of Lawshall, Michael Hare of Bruisyard and Roger Martin of Melford all refused to conform and were sent to prison in Ipswich. John Daniel of Acton, Edmund Bedingfield of Denham and Henry Everard of Linstead and several others were sent to houses in Bury for their "imprisonment". Others like Edward Sulliard were sent to houses in Ipswich. Later, when Bedingfield was sick, he was allowed to move to Leiston Abbey, and the following year he was allowed to take the waters in Bath. Those in prison were sometimes moved out to private houses, and bailed to avoid the plague.

By this time John Copping had remained in prison two years for holding religious opinions of an extreme Puritan nature. Because he was still refusing to conform, he was brought before Justice Andrews in December 1578, when his "false and malicious opinions", were proved against him. Having refused to change his opinions, once more he was remanded to prison where he remained almost five years more. At some point he would be joined in prison by Elias Thacker, another minister of the same opinions.

|

|

1579

|

In February, four apparently puritan JP's at Bury issued their own code of discipline for the parishioners of St Mary's church. Penalties were laid down for gaming, usury, fornication and drunkenness, but also for keeping monuments of idolatry, papism, absence from church, disturbing prayers, blasphemy and witchcraft. These JP's were Robert Jermyn of Rushbrooke, Thomas Andrews of Bury, John Higham of Barrow and Robert Ashfield of Stowlangtoft. Thomas Andrews was a leading Feoffee and was much more conservative in his views than Jermyn or Higham.

|

|

1580

|

In October 1580, Edward Rookwood of Euston was in Norwich Gaol for recusancy. He was held there with Humphry Bedingfield, and the Suffolk recusants, Michael Hare, Roger Martin and Edward Sulliard. In prison he received a plan of escape sent to him by English Catholics living in France. He burned the letter, but not before the Bishop heard about it. Rookwood had to persuade the Bishop that he was loyal to the Queen and had no thought of treason.

|

|

1581

|

An Act of Parliament said that anyone staying away from church services could be fined £20 for every month in default. This was aimed at Catholic recusants, but there was a group of protestants who preached Separatism from the Church of England.

Robert Browne (1550?-1633) was a prominent Elizabethan Separatist. He was born in Tolethorpe, Rutlandshire, of a wealthy and prominent Northamptonshire family. Browne attended Cambridge University 1570-73. He received a B. A. (1572) from Corpus Christi College (Cambridge).

It was while Browne was at Corpus Christi, that he first met Robert Harrison (154?-1585?). Harrison came from Norwich. In 1578 Browne became a member of the household of a Puritan clergyman at Dry Drayton outside Cambridge, the Rev. Richard Greenham. This “preaching minister” was one of those who remained loyal to the Church of England, but clung resolutely to simplicity of dress and worship. Browne preached in the area, but because of his objections to Bishops and church regulations, he refused to ask for a proper preaching license. He left the Cambridge area after about 6 months and Browne was able to persuade Harrison to establish their own Separatist congregation at Norwich early in 1581 based on their own ideas. At Norwich there was a large Dutch and Walloon population, sympathetic to radical Protestant ideas. This group is recognised as the first of what is now called the Congregationalists. Browne was also engaged in preaching at Bury St. Edmunds.

Browne's followers were the so-called Brownists, and they were active in Ipswich, Mildenhall and Thetford, but above all, at Bury St Edmunds.

On 15th April, 1581, the Bishop of Norwich, Edmund Freke, visited Bury St Edmunds to assess the situation. He was so concerned that he wrote to Lord Burghley to report on separatist meetings held in this town. The Bishop told of meetings, "to the number of a hundred at a time in private houses and conventicles" to hear Robert Browne preach. The Bishop feared that expression of such radical views to such numbers was "not without danger of some ill event." He found "great divisions amongst the people."

In 1581 the separatist leader, Robert Browne, was put in prison by order of the Bishop of Norwich for his unlicensed and seditious preaching at Bury. By 1591 Browne had returned to the Church of England in Northamptonshire, but his followers kept his old ideas alive. The Congregationalists or Independents would later follow very similar ideas.

Unfortunately the separatist movement had the knock-on effect of reinforcing opposition to much less militant non-conformists. In 1581, town preacher at Bury John Handson had his preaching licence suspended by the Bishop of Norwich.

|

|

Pope Gregory's new calendar

|

|

1582

|

On 24th February, 1582, Pope Gregory XIII announced that the Catholic world was to adopt a new calendar, named the Gregorian calendar.

This edict did not cover this country and the system was not adopted here until 1752. In England, Scotland and Wales, the new year continued to begin on Lady Day, 25th March, and would be 10 to 11 days behind the new Gregorian system for the next 170 years.

There was no hope of adopting any calendar of the Pope's while Puritans like the rector of Cockfield had any say. In 1582 John Knewstubb, who was a well known and prominent puritan, called a secret conference of 60 East Anglian clergy at Cockfield to discuss what parts of the prayer book they would accept or reject.

Bury St Edmunds was in the midst of a religious turmoil known as the "Bury Stirs". Certain Puritan leaning Suffolk magistrates like Sir Robert Jermyn and Sir John Higham were frequently in dispute with the Bishop of Norwich, Edmund Freke. Similarly, within the town, there were those inclined towards Puritanism, who considered themselves to be Godly men, who were constantly at odds with the more conservative supporters of the official church doctrines. This enmity led to underhand tricks and misrepresentations, followed by appeal and counter-appeal to the authorities.

James Gayton, the Town Preacher for St Mary's parish, left Bury St Edmunds in early 1582, unable to bear the situation any longer. In June John Handson also left the town, blaming, "the violent and continual practices...of some men's malice."

By August, 1582, both of Bury's town preachers, John Handson and James Gayton, had left the town because of the conservative hostility to their preachings. This caused 174 local men to appeal to the Privy Council to send commissioners to enquire into the matter. Town preachers were paid by contributions from parishioners, and the failure to meet these payments, on the part of some objectors, was the material reason why they had to seek "employment" elsewhere.

One further incident which inflamed the situation involved the royal coat of arms which was displayed in St Mary's church. Some townsmen had organised the painting of part of a verse from Revelations around the Queen's arms. The inscription of part of Revelations chapter 2, verse 19, was taken as a direct criticism of Queen Elizabeth and her church. This graffitto was seen as treason in official quarters, and was to be quoted as evidence against any form of dissent.

This verse seems innocent enough on its own:

"I know thy works, and charity, and service, and faith, and thy patience, and thy works; and the last to be more than the first."

but it merely introduces the next verse which goes as follows:

"Notwithstanding I have a few things against thee, because thou sufferest that woman Jezebel, which calleth herself a prophetess, to teach and to seduce my servants to commit fornication, and to eat things sacrificed unto idols."

The implication that the Queen is equated with Jezebel makes this inscription much more serious than it first appeared.

The underlying issue was the Reformation itself. How far should reform go? The crown wanted to keep the peace by fixing upon an official form of worship, which it hoped would appeal to all sides. This was supported by the Bishops and the church hierarchy. Those who wanted to go further covered a spectrum of beliefs from merely rejecting the wearing of the surplice or the clerical hat, to those who rejected the idea of a church hierarchy of any description. These were the separatists, or Brownists, who wanted to set up a separate congregation untramelled by the rule of Bishops.

It is fair to say that both sides misrepresented the ideas of their opponents in order to discredit them, and both sides refused to accept the good faith of the other. The Puritans referred to everybody else as "irreligious persons", or "backward men in religion". Bishop Freke in 1581 had referred to the non-conformists as "those given to fantastical innovations" as compared to those who had a "dutifull affection to have Her Majesties proceedings observed", and it was a "vulgar sort of people" who favoured innovation.

The conservative elements within the town who opposed the radical views of the town preachers were mainly the Governors of the Grammar School and the Guildhall Feoffees. Of the 24 Feoffees, only Thomas Badby had broken ranks and signed the petition to the Privy Council on behalf of the town preachers. Although small in number, the Feoffees had power and influence within Bury St Edmunds, and could command a hearing by the highest in the land.

By November John Handson had returned to Bury, persuaded back by his flock who promised to stand by him. On 6th November, they wrote another appeal to Lord Burghley, signed by 144 inhabitants. The appeal said that Handson had returned as he was "sent for by a general consent", but "he will not execute his office" until he was sure of a peaceful reception. The letter claimed the support of 400 parishioners, against "the false accusations of of a few infamous persons who cannot abide the godly preacher of the word."

Because of the general air of dissent and tension in Bury St Edmunds in 1582, the Assize judges avoided a sitting in Bury during this year.

|

|

Thacker & Copping Memorial

|

|

1583

|

More and more Puritans were questioning the legitimacy of the established church. The most extremely outspoken were often jailed. In 1582 Robert Browne had published his tract called "A Book which sheweth the Life and Manners of all true Christians" which was so inflammatory that he moved to Holland, where he also wrote "Treatise of Reformation without Tarrying for Anie" By 1583, the writings of both Browne and the like minded Robert Harrison were being sold in England. In mid-1583 a Proclamation was issued against the buying, selling or owning the dissident works of Robert Browne and Robert Harrison.

By 1583, the Reverend John Copping had been on remand in Bury St Edmunds goal for seven years. At some point he was joined by Elias Thacker, prosecuted for distributing Browne's pamphlets. Although imprisoned, their preaching so undermined good order in the jail that something more had to be done. They tried to get a writ of Habeas corpus, but at the trial the prosecution barrister associated them with the seditious graffiti around the Queen's coat of arms found in St Mary's Church the previous year. The sentence passed upon them was founded upon the 23rd Eliz. law against seditious libels, and for refusing the oath of supremacy. They acknowledged the supremacy of the queen in civil matters only, not in matters ecclesiastical, thereby subverting the constitution of the established church.

The Judge passed the death penalty, and both men were sentenced to hang at Tay Fen, just outside the line of Bury's ancient wall. The authorities collected together all that could be found of Brown's books, prior to their execution, and burnt them before their eyes. Lord Chief Justice Wray claimed that there were many of Copping and Thackers' opinions in the town, and that the example made of them would act as a deterrent.

Only one man was convicted of arranging for the defacing of the royal arms. He was Thomas Gibson, a Bury bookbinder, who was fined for his part in the action.

A minister was later convicted for claiming that if the executions had taken place a year earlier, there would have been another 500 people in the crowd at the hangings. Clearly by 1583 the reforming zeal had been damped down somewhat within Bury St Edmunds. Nevertheless these ideas were widespread in West Suffolk. At Thetford, the separatist preacher William Dennis was also hanged in 1583.

Meanwhile Browne, the well off and well connected writer of the pamphlets, was free at large while others were being arrested and hanged for selling his books. Browne himself has often been called the father of Congregationalism.

In Whiting Street there is a memorial to John Copping and Elias Thacker, hanged in 1583 for distributing puritan literature and supporting independency. This memorial was erected in 1904 in the grounds of the Congregational Church.

Thomas Badby, a leading puritan JP, who lived in Bury St Edmunds, died on 7th December, 1583. He had recently been ejected from the Commission of the Peace for his puritan zeal. Sir Robert Jermyn, another puritan, felt moved to appeal to Lord Burghley on his behalf as recently as November 22nd, citing an "unworthy and unlawful minister", as the cause of his eviction and fine of 100 marks.

|

|

1584

|

Over 50 Suffolk ministers were suspended for refusing to conform to the official Protestant Church of England teachings including a refusal to wear the surplice. Puritanism continued to spread, despite official persecution.

In Bury, since the Dissolution of the abbey, the town had fallen under an increasingly oligarchic administration by the capital burgesses. The inhabitants complained to the crown and a commission was appointed to look into how the Feoffees were administering the town lands. To some extent this was a move by the puritan leaning townspeople against the conservative Feoffees, and, in particular, Thomas Andrews, in revenge for their attacks upon the town preachers.

Sir Nicholas Bacon, Sir Robert Jermyn and four others, Robert Ashfield, John Jermyn, Thomas Poley and George Kemp, were appointed by the Privy Council for the task on 20th December, 1584.

|

|

1585

|

On 28th April, 1585, The Commission appointed to examine the accounts of the Feoffees sent their report to the Privy Council. They found that the Feoffees had ignored the terms of the bequests they administered. They had accounted to themselves and not to all the burgesses, contrary to the express words of the will of the main donor. They alone had been appointing their successors, which was a job for all the burgesses. Town houses had been sold off to friends at below market price, and they had kept the best leases to themselves at 12d per acre when they were worth 5 shillings. In addition a compromise position which had been reached and agreed in January between town and Feoffees was being flouted. They were found guilty of maladministration and peculation.

Thomas Andrews, a conservative Feoffee who had led the legal machinations against the townspeople, died during 1585, and for the first time, there was a proper Michaelmas accounting by the Feoffees. The list of signatories now included Sir John Higham and four men who had petitioned in favour of the town preachers. The "godly" faction had at last gained the upper hand in Bury St Edmunds, and this ascendancy of puritan thought would prevail for decades to come. The town, the Feoffees and the School governors were all now in puritan hands.

|

|

Miles Moss at St James

|

|

1586

|

In 1586 Miles Mosse became the Reader, or town preacher, at St James in Bury St Edmunds at a salary of £48 a year. Miles Mosse was the son of Miles Mosse of Chevington, and was born in 1558. He was educated at Bury Grammar School and Caius College, Cambridge, gaining his first degree in 1579. In 1585 he became vicar of St Stephens in Norwich, and was soon recruited to his home town of Bury. He had gained a reputation as a preacher, and the delivery of learned sermons was regarded as the prime responsibility of any church.

Mosse was now supported in his puritan leanings by the majority of the town, unlike the position of his predecessors in the post, just a few years earlier. Illustrative of this sea change in control are the Feoffee accounts, which showed between £2 and £4 a year spent on both parish churches and their ministers from 1582 to 1585. In 1586, after the demise of Thomas Andrews, and the enquiry into Feoffee accounts, expenditure on church and ministers shot up to £50. In 1588 it would rise to £58 and by 1589 it reached a level of £82, where it would stand for another decade.

One of the new Reader's duties was to give the regular Combination Lectures, held on Mondays. These were open to both clergy and to lay people. Mosse seems to have thought that this provision could be improved upon, and he soon extended them.

Mosse was keen to train the local clergy, and he set up classes at St James on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, which were attended by lay people as well as by the ordained. He soon realised that he needed a number of books to help with his teaching, and he would be responsible for building up a library of books at St James which survives today. The illustration here is from a book which he gave to St James library when it was formally established in 1595.

|

|

1587

|

Another Act was passed against Catholics refusing to pay their fines for recusancy. They could lose all their goods and two thirds of their lands. The £20 a month fine was paid by Edward Rookwood of Euston, Edward Sulyard of Haughley, and Michael Hare at Bruisyard. Roger Martin of Long Melford not only paid over £200 in fines but after 1587 lost his income from his lands to the state. Edward Rookwood was eventually ruined by a combination of fines and the cost of building Euston Hall, one of the biggest houses in Suffolk.

|

|

Armada off Suffolk July 1588

|

|

1588

|

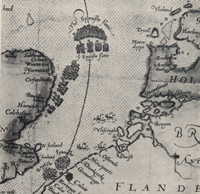

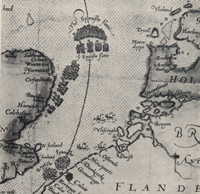

In 1588 the country was expecting an invasion by Spain. All over England men were mustered to join the military. Chevington has records of nine men put under arms supplied by the local Paman family and other local gentry. This map was published in 1590 and is now in the British Museum. In August a Suffolk contingent were marched to Tilbury Fort under Sir John Heigham of Barrow Hall, High Sheriff of Suffolk.

These land defences were not needed as the Spanish Armada was defeated by Sir Francis Drake. However, the threat of domination by a foreign Catholic power helped to stir up further pressure to be put on Catholics refusing to go to church, who were also seen as potential traitors to the crown.

Despite Sir Thomas Kytson's promises to Queen Elizabeth to observe the new religion, both Thomas and his wife Elizabeth were included in a list of recusants compiled in 1588. They lived at Hengrave Hall.

|

|

1590

|

By the 1590's Suffolk Puritanism was so strong that about a third of the clergy had been reported for refusing to wear the surplice. The surplice itself had been a Church of England simplification of the original Catholic vestments. Puritan clergy were installed by Puritan patrons of their livings like Sir Robert Jermyn of Rushbrooke and Sir John Higham of Barrow. These two men alone controlled 15 benefices.

However, there were some strongly Catholic members of the gentry willing to take risks. In 1590 the Jesuit priest John Gerard spent a year with Edward Rookwood at Euston Hall.

|

|

1591

|

The Jesuit priest John Gerard moved from Euston Hall to spend about a year with Henry Drury at Lawshall.

|

|

1593

|

An inspection or 'visitation' of the Archdeaconry of Sudbury reported 81 ministers for refusing to wear a surplice. This was a sign of extreme protestant views, which were out of step with the Queen's Reformation rules.

This was not just the case in urban areas. At St Andrews Church in Barningham the rector, Andrew Carter, "doth not usually wear the surplice, nor usually say service upon the week days. He preacheth, but whether licensed or no, they know not."

Churchmen had to be licensed to preach without a script, and the approved sermons were published in 1562, and re-issued over the years. This was the Book of "Certain Sermons or Homilies, appointed to be read in Churches." It contained 33 sermons in the 1683 edition, and if the incumbent was not licensed to preach, then he had instead to read out one of these homilies at his services.

Andrew Carter seems to have avoided any extreme official censure, as he was rector of Barningham from 1584 to 1624, a remarkable 40 years.

|

|

Sermons from Bury

|

|

1595

|

The sermon, that ‘immortal seed of regeneration’, was a central concern of the Elizabethan and Jacobean church. The Bury St. Edmund’s lecturer, Dr Miles Mosse’s "The Arraignment and Conviction of Usurie" was originally delivered in six sermons at Bury. The treatise was published in book form "by the Widow Orwin for John Porter", in 1595. Mosse included a long dedication to the Archbishop of Canterbury which he concluded with the dateline, "Bury St Edmunds this first of Ianuarie. 1595."

According to a University of Paris website, Miles Mosse was the son of Miles Mosse of Chevington, and was born in 1558. He was educated at Bury Grammar School and Caius College, Cambridge, gaining his first degree in 1579. In 1585 he became vicar of St Stephens in Norwich. In 1586 he became the Reader at St James in Bury St Edmunds at a salary of £48 a year. He would be Rector of Combes in Suffolk from 1597 until his death in 1615.

Mosse has been credited with producing the most elaborate discussion of usury in the latter part of the sixteenth century. Such a work and the debates it inspired would be reflected in William Shakespeare's play, "The Merchant of Venice", produced in 1619.

To compose an effective sermon, access to books was considered crucial. Mosse cited one hundred and fifty seven authors, prefacing his work with a list of pre-Reformation authorities running into several pages. These books had most likely been in the hands of the great monastery libraries before 1539.

The library of the abbey of St Edmund had long since been broken up, and individual collectors had acquired some of these books. Unfortunately we do not know the source of the books quoted by Mosse, or who their current owners were. Mosse saw that it was essential to build up a new library in Bury St Edmunds for use in the education of local clergy. As he was the lecturer at St James's, (now the cathedral), the new library was instituted at the east end of the north aisle of that church. Mosse generously donated volumes on various topics from his own collection. He continued to donate items, as did other rich local patrons of the church. By 1599 the St James library would hold 138 titles.

J S Craig has suggested that the St James Parish Library was the first parochial library of its kind in the country, as distinct from collections of prescribed texts or school books.

|

|

1597

|

The Bishop of Norwich found that 81 of the church ministers in the Archdeaconry of Suffolk were refusing to wear the surplice, a sure sign of extremist puritan beliefs. Together with the 83 found in the Sudbury archdeaconry in 1593, this meant that about one third of the clergy in the County of Suffolk were Puritans.

|

|

King James I

|

|

1603

|

Good Queen Bess died and King James VI of Scotland became James I of England on 24th March, 1603, the first Stuart to rule England. The new king had been King of Scotland since 1567, when only a child. James I would reign until 1625.

James I had more extreme religious views than had Queen Elizabeth I, who believed in keeping things as moderate as possible in an attempt to keep most people happy. James had a strong belief in witchcraft, and so a new Witchcraft Act was passed which gave the penalty for practising witchcraft to be death by hanging.

|

|

Coldham Hall 2009

|

|

1605

|

A failed attempt to blow up Parliament became known as the Gunpowder Plot. Bury St Edmunds and its surrounding countryside still held many Catholic families, many of them officially recorded as recusants, that is they refused to attend Protestant services. It was not unusual to install priest holes into their grand houses in which a travelling priest could hide in the event of a visit from the authorities. Nicholas Owen of Oxborough Hall in Norfolk was the architect of many such installations. At Coldham Hall in Stanningfield, Ambrose Rokewood had such a priest hole in his house. Coldham Hall had been built by his father, Robert, in 1574. Ambrose Rokewood was a rich young Catholic with a reputation for his stable of fine horses. Somehow, very late in the Gunpowder Plot, he was persuaded to supply the plotters with swift horses for their escape. The plot was discovered on November 5th 1605, and by the following January the plotters, including Rokewood were hanged, drawn and quartered for treason.

Ipswich had been appointing Puritan town preachers since the time of Queen Elizabeth. The most notable of these was to be Samuel Ward, the son of John Ward, the Puritan preacher from Haverhill. At the age of 28, Samuel was appointed Town Preacher for Ipswich on 1st November, 1605. His uncompromising views on how the Reformation should be carried forward were fully supported by Ipswich town and corporation, and he remained in this post until his death in 1640.

|

|

1606

|

Following the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, Parliament passed the 1606 'Act for the better discovering and repressing of popish recusants'. The churchwardens and constables of towns were required to bring to the Quarter Sessions all the recusants who had not attended a Church of England service for a month.

|

|

New Testament of King James Bible

|

|

1611

|

The King James, or Authorised, Version of the Bible was published, and is still printed today. It arose from the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, and was proposed by John Reynolds, a moderate Puritan. The existing Geneva Bible included criticism of monarchic rule in its annotations, and King James was keen to remove these. Fifty four translators were appointed to go back to the original Greek in order to correct and amend the Bishops' Bible, and produce a format for use in reading in church. The Geneva Bible would retain its popularity for another 40 years, before the King James Bible became fully accepted. This particular volume was given to the library of the Cathedral of St James in 1934.

|

1613

|

As if to confirm his removal from Hawstead Place to Hardwick House, Sir Robert Drury obtained a license to have divine service read in his new house at Hardwick. Thomas Ridley, the Archbishop of Canterbury, granted the license to include his wife, his servants, and the widows from his newly founded almshouse. Hardwick appears to have now become an extra-parochial district.

|

|

|

James I and three charters

|

|

1614

|

The town of Bury St Edmunds received a final Charter from James I which gave it the right to send 2 MPs to Parliament, and to hold a court of quarter sessions. The corporation were so pleased with their three charters that a painter called Fenn was commissioned to picture the king with a representation of the three documents, as shown here.

The latest writ also gave other new privileges to the town's council. Any earlier benefactions given to the Alderman and Burgesses in monastic times were confirmed to the new Corporation. Therefore, the churches of St James and St Mary now also came under the corporation's wing. They claimed the same episcopal exemptions won by abbot Baldwin, so that the corporation could appoint the local clergy themselves. This right lasted up until 1842, when the corporation sold these rights. Previously, from 1539 until 1614, the right to appoint the clergy had been exercised by the Feoffees of the Town Lands. They had set up a library at St James Church, and this also passed to the Corporation in 1614.

|

|

1615

|

Samuel Ward, a puritan preacher from Haverhill, had his first book of Sermons published in 1615. There is a school in Haverhill named after him.

|

|

1620

|

The Pilgrim Fathers landed in America on the Mayflower.

By 1620, Haverhill had become well known as a Puritan town. It produced many leading Puritan preachers such as the Ward family (John, his sons Samuel and Nathaniel and his grandson John), the Faircloughs and the Scanderets.

|

|

1623

|

Things were desperate in many parts of the country, and Bury was no exception. It is thought that a workhouse had existed in the town before 1621, located in a house in Whiting Street. In 1623 a house in Churchgate Street was adapted to take over the role of workhouse.

Along with the new workhouse, St Peter's Hospital in Out Risbygate had just been refitted as a house of correction. The massive growth in poverty and near starvation was met by a growth in workhouse and correctional places.

A notable Puritan in the Haverhill area was Sir Nathaniel Barnardiston, who had the gift of three Suffolk livings. In 1623 he appointed Samuel Fairclough as Rector of Barnadiston. Fairclough was a famous puritan preacher, "mighty in the scriptures". Kedington Hall was the home of Sir Nathaniel and his servants were selected for their piety and sincerity. The house was run like a continuous prayer meeting, with psalms and prayers at every meal.

|

|

1627

|

King Charles I started to try and increase the amount of money paid for Catholic recusancy. He brought in a new system to replace monthly fines, but payments were steep. In 1627 he took £103 in such fines from Suffolk, but by 1634 this had risen to £728. As this could only be paid by the wealthy, it helps to explain why Suffolk Catholics did not rush to the king's side in the Civil War.

In addition the King levied a "forced loan" on the country without Parliamentary support. In Suffolk, several men were imprisoned for refusing to comply. Among them was Sir Nathaniel Barnardiston, who was, as well as a Puritan, a strong defender of the rights and privileges of Parliament. He was a Suffolk MP from Kedington.

However, under Charles I, high church practices would increasingly be introduced into the English church.

|

|

1629

|

Charles I dissolved Parliament and determined to govern without it for the next eleven years. This period is called The Personal Rule of Charles I. Charles had been king for only four years and at first he managed well enough without Parliament. However,in one regard he was stirring up resentments. He sponsored William Laud's high church teachings against the current mainstream of Anglican sensibilities.

|

|

1630

|

The Corporation at Bury conveyed all their property, including the markets, fairs and tolls, to 40 trustees. The reasons for this seem to be unclear, and there is suggestion that they feared the charter was about to be withdrawn. Bury corporation were strong supporters of Parliament, and the King had taken many personal decisions against those who resisted his arbitrary rule. This matter of the ownership of the corporate property became an issue in the 1660's.

The 1630s were a period of continuing religious tension. There was a division between the renewal of high church practices and a continued development of puritan ideas, which rejected elaborate, organised and hierarchical forms of religion.

Sir Nathaniel Barnardiston appointed Samuel Fairclough, his fiery puritan Rector of Barnardiston, to the living at Kedington, as Rector. The influence of such men made the Haverhill area a stronghold of Puritan values.

Nationally, as well as locally, large scale emigration to Massachusetts now began. In 1628 a group of Puritan investors had set up the "The New England Company for a Plantation in Massachusetts Bay" to help people emigrate to the New World, seeking religious freedom.

In East Anglia, pre-reformation church practices were returning in most areas and influential puritans like Winthrop could not accept this. In addition there was a depression in the area, and in April, 1630, 112 men, women and children left Suffolk for America, including John Winthrop.

|

|

1633

|

In America Agawam remained an uncolonized part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1633 when Governor John Winthrop sent his son, John, to establish a settlement to be called Ipswich. It was an strange group of settlers who came to Ipswich - men of substance and education, who were among the key founders of the Puritan Commonwealth: Thomas Dudley, Deputy Governor; Magistrates Simon Bradstreet, Richard Saltonstall, and Samuel Symonds; and Ministers Nathaniel Ward, John Norton, William Hubbard, and Nathaniel Rogers. Nathaniel Ward was a preacher from Haverhill in Suffolk, a brother of Samuel Ward, at this time the Town Preacher at Ipswich in Suffolk.

From 1611 to 1633 George Abbott had been Archbishop of Canterbury, a man of puritan sympathies. During his reign men like Samuel Ward, Town Preacher of Ipswich, had largely got away with preaching puritanism, offending the Spanish ambassador, attacking the Duke of Buckingham and opposing church ceremonies. This attitude would change in late 1633.

The newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury was William Laud, a man who tried to impose "high-church" rituals and discipline upon the clergy. With such a strong puritan feeling in the Country, this was a great mistake, but he was supported by the King.

In reality he was probably more against the rising puritan practices than pro-catholic, but a new harder line was being drawn.

|

|

1634

|

Samual Ward, the puritan town lecturer of Ipswich for 30 years past was hauled before the Court of High Commission for praying informally and criticising Church hierarchy. Samual Ward was also accused of inciting emigration to New England.

|

|

1635

|

A new Bishop of Norwich was appointed, called Matthew Wren, a supporter of Laud's high church ideas. He cracked down on East Anglian puritanism.

Samuel Ward was censured in the Court of High Commission in November 1635. He was suspended from his job, and then imprisoned. Ipswich refused to replace him as they wanted Ward for Town Preacher, "or nobody".

|

|

1636

|

The new Bishop of Norwich, Matthew Wren, stayed at Ipswich in 1636 and suspended some of the Suffolk clergy for refusing to accept certain new high church disciplines. Puritan local lecturers like Edmund Calamy at Bury, and Samuel Ward at Ipswich were excommunicated. The Puritan response was that Bishop Wren of Norwich was accused of driving out the god-fearing by his "popish idolatry." There were riots in the streets of Ipswich over it.

For ten years Edmund Calamy had been preaching to a packed church of St Mary's in Bury. In 1633 the government had felt obliged to issue lists of games, called the "Book of Sports", which could be played on Sundays without necessarily profaning the Sabbath, which included Morris Dancing and May games. Calamy had refused to read out this list in church as he disagreed with it. Puritans thought that the whole of Sunday should be for worship, and that no sport whatsoever should be played on a Sunday. After being sacked from the church he moved to London and would edit the "Soldier's Pocket Bible", a Puritan best seller during the Civil War.

Bishop Wren really put the cat among the pigeons when he insisted that the Communion Tables should be moved to a railed off part of the church at the east end, thus reinstating the Catholic Altar. Communicants had to kneel at the altar rail instead of receiving communion in their seats as had been the way since the Elizabethan Reformation.

|

|

1638

|

By 1638 some 6-800 people from Suffolk and 1200 from Norfolk and Essex had sailed to Virginia despite government attempts to keep them at home. These new plantations were very largely successful, "beyond the hopes of their friends, and to the astonishment of their enemies." Religious zeal and a desire for freedom of worship characterised some of the emigrants.

Many of these migrants came from Ipswich, Sudbury, Haverhill and Wrentham, all puritan strongholds in Suffolk.

The high churchman, Bishop Wren of Norwich, lost his bishopric in 1638. He had been Bishop of Norwich only since 1635, but had stirred up a hornets nest in Suffolk and Norfolk by his high church reforms. In 1642 he was impeached by the Puritan parliament for his high church ways. When accused of driving good puritans to emigrate, Bishop Wren himself blamed emigration on the low wages caused by the depression in the cloth industry in those areas.

Many people consider that the Puritan movement was greatly strengthened by public distaste for the reforms of Archbishop Laud. Bishop Wren himself had turned Norfolk and Suffolk into puritan strongholds. As a popular movement in Suffolk, Puritanism had many more active supporters in 1640 than it had in 1630.

|

|

1640

|

In Suffolk, only £200 of the ship money assessment for the County of £8000, was paid. Rich men like Puritan Sir Nathanial Barnadiston were among those who refused to pay up on moral or religious grounds.

Once the invading Scots had taken Newcastle in the Autumn, the King had no option but to recall Parliament again. After the long Parliament had started in November, 1640, its puritan majority began to change the face of national religion. Parliament was now on a collision course with the King.

|

|

1641

|

In June, 1641, a Bill was introduced by the Long Parliament for the abolition of episcopacy. In practice, the Bishops were to be abolished. Nineteen counties sent in petitions to support the bill, one of which was Suffolk. Puritans blamed the bishops, particularly Archbishop of Canterbury Laud, and the deposed Bishop Wren of Norwich, for the re-introduction of catholic practices into church services since the 1630's. One of the Bill's strongest supporters was Sir Simonds D'Ewes of Stowlangtoft. He ran a puritan household much like Sir Nathaniel Barnardiston, and had been elected MP for Sudbury.

All superstitious pictures and inscriptions in churches were ordered to be removed and defaced in 1641. There was another ordinance to this effect in 1643, but Suffolk did not necessarily suffer from this until 1644, following the appointment of William Dowsing. However, it does appear that in many places the local congregations supported Parliament's Puritan line, and where the local hierarchy were of a similar mind, the people themselves willingly carried out the Parliament's will.

In Ireland, 3000 Ulster Protestants were massacred by Catholics who had been disposessed by James I's Ulster Plantations Policy.

At some point before the war the corporation at Bury St Edmunds began to fear that their own parliamentary leanings may cause the crown to seize their assets. They seem to have devised a plan to vest the corporate assets in the Guildhall Feoffees to place them safe from the king.

|

|

1642

|

In January 1642 the House of Commons issued orders to disarm Royalists. Sir William Castleton, (the High Sheriff of Suffolk), Sir William Spring, and Maurice Barrow, esq., were ordered to search the Suffolk house of Lady Rivers, seize any arms they found, and put the arms into safe custody. This order referred to Melford Hall.

Later in January, on the 25th, Hengrave Hall was also searched by the same gentlemen, and large quantities of arms removed by their 30 attendants. Hengrave was the home of Lady Penelope Gage, the sister of Elizabeth Savage, although the property belonged to Countess Rivers. Lady Penelope protested that the arms and armour had been in Catholic hands for 100 years, "and never yet hurt a finger of anybody", but to no avail. The Gages were prominent Catholics, and Lady Penelope wrote to Countess Rivers of being "daily threatened by the common sort of people".

Even before the war began, Bury St Edmunds was one of only 22 places in England to raise volunteers for the Parliament. Men like Thomas Chaplin, Bury Alderman and a linen draper would become active in the County Committee, as would Thomas Gibbs, a Bury Alderman, and Samuel Moody, another Bury Alderman and a cloth merchant. Such men would have recruited these volunteers.

On August 22nd, 1642, the English Civil War officially began when the King raised his standard at Nottingham. This phase is also called the First civil War, and would last from 1642 to 1646. Charles I was so unpopular because of ship money, and other arbitrary taxes, that Suffolk gentry in general supported Parliament. When it came to fighting, most of the gentry in Suffolk seem to have done their best to remain neutral, but undoubtedly the activists in Suffolk were a mixture of the puritans and parliamentarians. Ipswich, Lavenham and Aldeburgh were strongly for Parliament. Ipswich fortified itself against the King's fleet.

Gordon Blackwood has shown that in East Suffolk there were twice as many gentry supporting Parliament as supported the King. However, in West Suffolk, their numbers were very even, with only a majority of two in favour of Parliament.

Neither did Catholics fully support the King. Gordon Blackwood showed that of 34 Suffolk Catholic families, only six supported Charles I. Of the 64 Royalist gentry families in Suffolk, these six Catholic families made up a mere nine percent.

In Suffolk less than 100 prominent men and their families were supporters of the King and any non-puritan way of religion. They would be in peril as tension mounted. Riots broke out along the Stour Valley on the Suffolk Essex border. There was much unemployment in the cloth trade at this time, and the anti-enclosure movement both contributed to such riots. Men stood around with time on their hands, and religious and political issues could cover up the desire for revenge and the need for plunder.

One local Royalist who was willing to fight was Colonel Thomas Blague of Horringer. In 1642 he fought for the king at Edgehill, and would fight in many battles.

During the Commonwealth Stephen Scandarett was to become Haverhill's most influential nonconformist preacher, and a great local opinion-leader.

|

|

1643

|

In September Parliament took the Solemn League and Covenant. The intent was that everybody in the country would eventually have to swear an oath to accept the abolition of episcopacy and to reform the Church of England.

In September, Brandon was seized by the Parliamentary forces, and a garrison established there.

William Dowsing of Laxfield was appointed by Lord Manchester to be Parliamentary visitor for England in December 1643. He was to execute the ordinance of August 1643 for the defacement of superstitious images, pictures and inscriptions.

|

|

Dated inscriptions - Troston church

|

|

1644

|

William Dowsing, the Parliamentary visitor for Suffolk appointed deputies and they each took troopers to every church. One such deputy was Captain Clement Gilley of Troston. At his home church in Troston he apparently left alone the inscriptions on the church bells which had prayers for Katherine and Mary Magdalene. Elsewhere it was his custom to remove any prayers to the Virgin Mary and the saints inscribed on church bells. Gilley may have been responsible for whitewashing over the wall paintings at Troston, which were discovered again in the 19th century, and restored in 2009. Inscriptions from this period can still be seen in the Troston church of St Mary.

Dowsing himself visited 150 churches in 50 days. From 20th December 1643 until 2nd January 1644 Dowsing began his work in Cambridge. He worked in Cambridgeshire until 5th January, 1644 (modern dating), but also on that day he moved to Withersfield. It was his fourth church on that day.

"At Withersfield, we brake down 3 crucifixes and 80 superstitious pictures."

Dowsing arrived in Clare on Saturday 6 January. One of his deputies was Thomas Westhropp, who lived at Hundon. They visited Hundon church that day.

Moving to Sudbury on January 9th, they dealt with three churches there.

"Sudbury, Suffolk. Peter’s parish. Jan. 9 1643. (ie modern 1644) We brake down a picture of God the Father, 2 crucifixes, & pictures of Christ, about an hundred in all; and gave order to take down a cross of[f] the steeple; and diverse angells, 20 at least, on the roof of the church.

40. Sudbury, Gregory parish. Jan. 9. We brake down 10 mighty great angels in glass, in all, 80.

41. Allhallows [All Saints], Jan. 9. We brake about 20 superstitious pictures; and took up 30 brazen superstitious inscriptions, Ora pro nobis, and Pray for the soul etc."

Dr Dowsing visited St Marys in Haverhill on January 6th, and, in his own words,

"We brake down about 100 superstitious pictures and seven friars hugging a nun; and a picture of God and Christ; and diverse others very superstitious; and 200 had been broke before I came. We took away two Popish inscriptions with "Ora pro nobis", and we beat down a great stoney cross on top of the Church".

However, it seems that 200 superstitious pictures had already been destroyed by Haverhill people before Dowsing arrived.

At Clare, also on January 6th,

"We brake down a 1000 pictures superstitious; and brake down 200, 3 of God the Father, and 3 of Christ, and the Holy Lamb, and 3 of the Holy Ghost like a dove with wings; and the 12 Apostles were carved in wood, on the top of the roof, which we gave order have taken down; and 20 cherubims to be taken down. And the sun and moon in the east window, by the King’s Arms, to be taken down."

On 5th February, after crossing Suffolk, he stayed in Bury St Edmunds, where it is suggested that he may have lodged with the Moody family, relatives of Thomas Westhropp. His journal notes that

"Bury St Edmunds, Feb. 5. Mary’s parish. Mr. Chaplin undertook to do down the steps and to take away the superstitious pictures.

James’s parish. Mr. Moody undertook for."

On February 6th he was returning to Cambridge, stopping at some churches en route.

"At Newmarket they promised to amend all", presumably without too much prompting from Dowsing.

Thus in some places he was welcomed by at least some of the people. At others he met some resistance. Dowsing collected a fee from each church for his work of destruction. At Great Cornard the churchwarden, John Pain, refused to pay, and was arrested. Dowsing also noted another reluctant payer:

"Thomas Umberfield of Stoke [Tendryng Hall chapel, Stoke by Nayland], refused to pay the 6s. 8d. A crucifix; and divers superstitious pictures. Feb. 2"

Dowsing continued to travel Cambridgeshire and Suffolk carrying out his mission until October.

In March Lord Manchester appointed a panel of ten men to examine all the ministers and schoolmasters in Suffolk who were defying the will of Parliament or were scandalous in their lives, or were "fomentors of this unnatural war". They also had to administer the Covenant passed in the previous year. Any five of them were authorised to act and certify them to Manchester.

Two committees for scandalous Ministers were thus appointed to remove anti-puritan clergy in East and West Suffolk. Royalists were referred to as 'malignants' and high churchmen were called 'scandalous'. About 100 Suffolk clergy were evicted, including Richard Hart, Rector of Hargrave, and Robert Goodrick, Rector of Horringer. At Barningham the rector Randolf Gilpin had held the living since 1629. He had various disputes with his flock over the tithe arrangements, and they disliked him. He seems to have been evicted as early as 1642, possibly because the local Squire was Maurice Barrow, a man so in tune with the Puritan line that he was appointed to the County Committee for Scandalous Ministers.

In December 1644, a parliamentary ordinance was passed to abolish the celebration of Christmas, the most popular church festival of the year. This law would be largely ignored until 1647 when a further order became necessary.