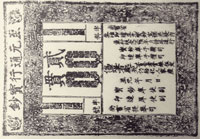

Chinese "paper" money

|

|

650AD

|

Paper was invented in China, and it was here that paper money originated between 650 and 800 AD. Chinese coins at the time were solely made of bronze, and to make up any large sum the weight of bronze required was prohibitive. This was in the T'ang dynasty and the paper was not itself in circulation, but was used as a promissary note, convertible into bronze when it reached its destination.

|

1000

|

With the coming of the Sung dynasty paper notes were becoming accepted for general tender. However, many small bankers arose who issued paper which they had not the means to convert into bronze coin, leading to a loss of confidence in paper money.

The government stepped in to issue its own paper, but also succumbed to the temptation to issue more paper than it had assets to back it up.

|

1278

|

The Sung Dynasty collapsed in 1278 because its over-issued notes caused runaway inflation. They were succeeded by the Yuan Dynasty, founded by Kublai Khan, (son of Genghis Khan) in 1271.

The Khan had not invented paper money, but his "paper" was issued on thin sheets of Mulberry bark.

|

| |

|

Marco Polo meeting the Great Khan

|

|

blank |

When Marco Polo arrived at the court of Kublai Khan in the late 13th century, he was astounded by the production of money printed on bark. He returned to Venice in 1295, and "The Travels of Marco Polo" was published in about 1300.

He described the Khan's minting of coinage, but could scarcely believe the production of bark notes.

Paper money was introduced as a new idea to western civilization by Marco Polo in a chapter of his Travels entitled: "How the Great Khan Causes the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over His Country"

|

1368

|

The Yuan dynasty also ended with their paper money becoming worthless as so much was in circulation.

|

1644

|

The Ming dynasty lasted from 1368 to 1644, and although they issued well made and impressive notes, these also became worthless because of over-issue.

Paper money was now abandoned in China until after 1853.

Banking in England

Since medieval times merchants had made their own arrangements for payment between themselves over long distances by the use of promissary notes of one sort or another. Occasionally these might be discounted by other merchants who relied upon the issuer to eventually redeem the full value.

Merchants who trusted each other might also use these promissary notes as security for loans, or as collateral to purchase goods from a third party. Goldsmiths would also issue receipts for valuable items put into their vaults for safe keeping. Such receipts might also be used as security for loans, and did get into a limited form of circulation.

|

1665

|

In 1665 King Charles II had an Exchequer Order issued which gave a legal status to the use of promissory notes.

|

1690

|

Through the 1680s there were about 50 London merchants whose promissory notes were widely trusted and accepted. Several of these men gave their names to banks which still survive today, with names like Barclay's, Lloyd's, and Coutts.

|

1694

|

In 1694 a Scotsman, William Paterson, founded the Bank of England. In 1695 he went on to found the Bank of Scotland.

|

| | | | |

|

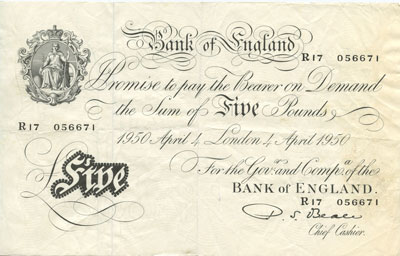

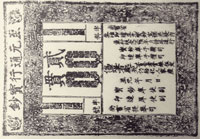

Bank of England note 1699

|

|

1695

|

The first paper money to be officially circulated in England was issued by the Bank of England in 1695. In the first year of production some 12,000 notes went ito circulation. At first only the fixed denominations of £10, £20, £30, £40, £50 and £100 were issued.

However, as can be seen from this example from 1699, the amount could also later be written in by hand.

|

1708

|

By Act of Parliament no bank could be set up with more than six partners. This provision would limit the capital available to banks, and would thus stop any one bank becoming too large.

|

1759

|

The Bank of England made further issues of notes from £20 to £100 in 1725, and in 1759 also issued notes for £10 and £15. At that time £10 was a substantial sum and small provincial bankers grew up who issued their own notes of less than £10.

|

1775

|

Another Act of Parliament now prevented any bank from issueing £1 notes.

|

1777

|

The Banking Act of 1777 made it illegal for banks to issue notes of £5 or less, ensuring that coinage, or specie in the terminology of the time, had to be used for this and lesser sums.

Specie is metallic money in all of its forms, gold or silver traditionally, but including nickel and copper as well. Specie is distinguished from other forms of money such as paper money or credit instruments like checks, promissory notes etc..

By now, however, there were small local "bankers" operating in most towns, although they would not operate "banks" as we know them today. They would also operate other businesses and most such banking was done alongside their everyday activities, from the same office.

|

1797

|

The wars with France led to a gold famine, and there was not enough gold available to pay out in specie. The Acts of 1775 and 1777 had to be repealed and the Bank of England now issued £1 and £2 notes.

|

| | | | |

|

|

|

blank |

Origins of local Banks

|

|

1770

|

Arthur Young recorded that in 1770 he was in debt to "the" Bury banker to such an extent that he had to visit him at his country seat at Troston to pacify him. He owed the banker around £1,000, and paid him off eventually, only with some difficulty.

Young does not name his banker, but the earliest bank in Bury St Edmunds was run by John Scotchmer, a draper. His bank closed when he retired in 1775.

By 1770 Arthur Young had spent the last three years away from Bradfield Combust, farming in Essex. However, he neglected his own property as he embarked upon a series of journeys through England and Wales. He reported his observations of real farming methods in books which appeared from 1768 to 1770. The major works were "A Six Weeks' Tour through the Southern Counties of England and Wales", "A Six Months' Tour through the North of England" and the "Farmer's Tour through the East of England". These were all well received by the public, and he made £1,167 income in 1770. However, he spent much more on his travels, his family at home, and his own agricultural experiments.

|

|

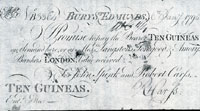

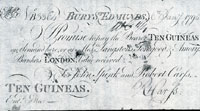

Spink & Carss note 1795

|

|

1775

|

In 1775 John Scotchmer, who is thought to have been the first banker in Bury St Edmunds, retired. It is unclear whether he overlapped with another of the early town bankers, John Spink, or whether Spink succeeded him.

In Bury, the draper, John Spink, was known to have been carrying out some form of banking activities before 1775. From 1775 he would gradually expand this side of his business to make Spink's Bank the largest such bank in Bury until its failure in 1797. By 1795 he had gone into partnership with his son in law, Robert Carss, also a draper. This banknote for 10 guineas dates from 1795, but is one of the earliest surviving local banknotes.

|

1776

|

In 1776, William Dalton opened a bank on the Cornhill at Bury St Edmunds. Like John Spink, he was already a businessman, but in this case Dalton was a Wine Merchant. This small bank never failed, but was taken over in 1794, by Edmund Squire, when Dalton died.

|

|

1784

|

Robert Walpole was a small banker in Bury St Edmunds whose main business had been as a draper. By 1791 he had retired from banking.

|

|

1787

|

James Oakes was the Duke of Grafton's political agent in Bury, and through the Duke's influence now became Receiver General of the Land Tax for the Western Division of Suffolk. In those days such an office meant that all money collected passed through your own personal bank account until the time came to make payment to the Crown. Jane Fiske has pointed out that the sums involved could reach £30,000 a quarter. Any interest earned in this time belonged to the Receiver, and was seen as remuneration for the job. Treasurers to various charities and other bodies also saw such arrangements as quite normal at this time. This substantial extra cashflow helped Oakes to decide to formally set up as a banker in 1794.

|

|

1788

|

In Sudbury the bank of Addison and Fenn opened. This was always a small bank, and after an involvement with Crowe, Sparrow and Browne, would be merged with the Oakes bank in 1830.

|

|

|

Home of James Oakes

|

|

1789

|

John Soane, later to become Sir John, met James Oakes to settle the design of the new wings to be added to Oakes' house at 81-82a Guildhall Street in Bury. In 1788 Soane had just begun to build his great design for the Bank of England, and this must have influenced his choice for this work.The northern wing was specifically designed as a banking office, but he was not yet the type of retail bank that we would recognise. This did not begin until 1794.

|

|

1792

|

The Universal Directory of Britain was published in 1791, covering places in England and Wales. It was published by the patentees of the idea, at the British Directory Office, Ave Maria Lane, London. Volume II contains entries for Bury St Edmunds, and refers to events in 1792, and so must have been published no earlier than this year.

After listing the Gentry, the Clergy, the Physicians and the Lawyers, the Directory went on to Traders etc.. These were all listed alphabetically by surname, giving their trade, but no address was given. First listed was "Apsey Michael, (F.) Ironmonger", and "F" denoted a Freeman of the Borough. A few examples included the following:

- Carss, Robert (F) Banker

- Spink John (F) & Carss, Bankers

The following were not listed, but Benjamin and Samuel Cook were two obscure men who offered banking services in Bury St Edmunds from about 1792 to 1797. Samuel Cook died in 1794 and Benjamin Cook's bank failed in 1797.

|

|

1793

|

About a hundred provincial banks failed in 1793.

|

|

1794

|

In September, 1794, James Oakes, a yarn manufacturer and coal dealer finally decided to set up a bank at his house in Guildhall Street, Bury. The architect John Soane was just building him two new wings to his house, and the northern wing would become a banking house. Within two weeks he was issuing his own notes. The Bury New Bank relied on Gurney's Bank of Norwich for technical backing. Oakes was already familiar with what we would nowadays recognise as banking practices because it was normal for bigger businesses at this time to provide credit and buy bills at discount, and even to issue promissory notes. Up to this time his major income had been in the making of yarn, but this was coming under increasing pressure from cheaper yarn from Ireland and Yorkshire. He needed to find an alternative business, and this was not easy in a an agricultural county like Suffolk. He had considered brewing, but seems to have felt more comfortable as a banker.

Banks already existed in Bury. William Dalton had been a banker here since before 1775, but when he died in 1794, his banking and wine business were acquired by Edmund Squire. This bank was on the Cornhill. Nearby was Spink and Carss Bank, also in business before 1775, and its draper founder, John Spink, also died in 1794. Robert Carss, his son in law was already a partner, and continued to run the bank. Samuel Cook seems to have been another Bury banker who died in 1794, but another man, Benjamin Cook, ran a banking business in Bury from 1792 to 1797 when his business failed.

|

|

1796

|

In July 1796 Oakes wrote that he had declined the wool trade and was now entirely confined to banking. This was still unusual for country bankers as most ran other businesses as well as their bank.

In Bury both Spink and Carss had also been drapers, as had been Robert Walpole, while Corks were also leather cutters and tea dealers.

With John Spink's death in 1794 Robert Carss continued the Spink and Carss banking business but made the mistake of building lavish new premises to house the bank, which helped to overstretch the banks finances.

|

|

1797

|

The wars with France led to a gold famine, and there was not enough gold available to pay out in specie. The Acts of 1775 and 1777 had to be repealed and the Bank of England now issued £1 and £2 notes.

In March, 1797, invasion scares led many customers to withdraw their deposits in cash from their bankers. Any banker who was overstretched would be vulnerable. Dr Charles Burney wrote to Arthur Young of a banker from Norwich who took £40,000 in notes to London to change at the Bank of England. But he was unlucky as the government had to suspend cash payments for a time, as the Bank of England ran out of gold and silver coinage.

Burney attributed these problems to "wicked and incurable democrats", and a Jacobin plan to break the bank. He recorded that the Duke of Bedford, and some manufacturers, had dismissed workmen because they had no cash to pay them.

Benjamin Cook's banking business in Bury collapsed in 1797, and the bank of Grigby and Cork of Bury failed on March 13th of 1797.

|

|

Spink and Carss Bank

|

|

blank |

The largest bank in Bury at the time was Spink and Carss. It was already weakened because its late proprietor John Spink, had died three years earlier in 1794, heavily in debt to the Treasury for taxes he should have collected as Receiver General for the Eastern Division of Suffolk.

From 1795 to 1797 Robert Carss had also built fine new premises on the Cornhill at great cost. Just two days after the failure of Grigby and Cork, on March 15th 1797, Spink and Carss failed. Robert Carss was Spink's son in law, and had been taken into partnership by John Spink.

|

|

Evidence in Bankruptcy

|

|

blank |

Several of Spink and Carss banknotes from 1795 survive because they were never cashed. As with the failure of any of these banks, it was not just the shareholders who lost money. Anyone who had accepted their notes, instead of gold or silver coins, was left holding worthless paper following a crash.

These became evidence in the subsequent hearing for bankruptcy. Two such notes are held by the Moyse's Hall Museum. The Trustees in Bankruptcy have added the following note to the reverse of these notes, thus: "At the Angel Inn, Bury St Edmunds 22nd April 1797, Exhibited to us under a Commission of Bankruptcy against Robert Carss. (signed) Capel Lofft, Thos Jas Case(?), indecipherable."

Oakes's bank now kept going all the better because it continued to pay out cash on demand, and thus survived its rivals' failures. The bank was even given a new name. It became the Bury and Suffolk Bank, and it was to be the sole significant Bury bank for the next four years. It gave up its relationship with Gurneys and indirectly Barclay's bank, and Oakes now used Ayton Brassey and co as his London banker.

At the same time Oakes's bank became the bankers to the Bury Corporation, taking over a loan of £2,350 made to it by Spink some time before 1778.

Despite the experiences of Spink's bank, being a Receiver of Taxes was still thought worthwhile and James Oakes got his son Orbell appointed to the West Division in this same year. In effect the job was handed on from father to son through the influence of the Duke of Grafton.

|

|

1801

|

Messrs Crowe Sparrow and Brown, who had only just established the Braintree Bank in 1801, bought Spink and Carss old banking house on the Cornhill, and opened up a new bank branch in Bury.

Crowe, Sparrow and Browne styled themselves at Bury as the Suffolk and Essex Bank.

Crowe's son in law was George Moor, who had been a clerk with the failed Spink and Carss bank. Moor had eloped with Crowe's daughter while she was at school in Norfolk. He was now to work at Crowe, Sparrow and Browne's bank.

At some point in the early years of the century, the bank of Crowe, Sparrow and Brown acquired some sort of involvement with the Sudbury Bank of Addison and Fenn. This may be the time in which that bank reversed its partnership name to Fenn and Addison.

|

|

1806

|

James Oakes opened a branch of his Bury and Suffolk Bank in Stowmarket to compete with Crowe, Sparrow and Brown who had been in Stowmarket since 1795.

Stowmarket was enjoying rising prosperity at this time. Farmers were doing well in the war, and the Gipping Navigation had opened in 1793.

In 1806 the Norfolk and Suffolk General Bank of Thetford opened a branch in Bury. This bank was owned by Willett and Sons.

|

|

1807

|

In 1807 the Suffolk and Essex bank of Crowe, Sparrow and Brown became Sparrow, Brown, Hanbury, Savill and Moor.

|

1813

|

With the end of the war with France in sight farm prices began to collapse, and for the next decade farmers would be in financial difficulties. Most of the population still relied on agriculture, even if they were not themselves the landowner or the farmer. As farmers got less money for their crops, they could not pay the wartime levels of land rents, and also tried to reduce their production costs by reducing farm workers' wages. Agricultural depression meant misery and economic Depression on a wide scale.

|

|

|

Bury and Suffolk bank £10 note |

|

1816

|

This ten pound note was issued by the Bury and Suffolk Bank of James and Orbell Oakes on 17th April, 1816. Like all provincial banks they themselves used London Bankers for support and public confidence. The note is decorated by an oak tree in the centre and the arms of Bury St Edmunds to the left.

|

|

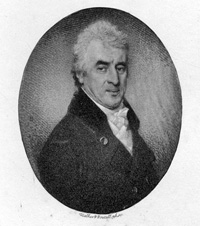

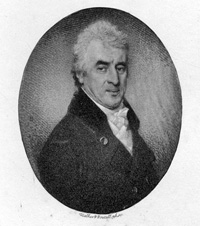

Arthur Young |

|

blank |

Arthur Young of Bradfield Combust was still Secretary to the Board of Agriculture, despite his age and his blindness, which had crept up on him after 1807. Now well into his 70's he was still coming up with proposals to further the work of the Board. In February he proposed and masterminded a great postal survey of the real state of agriculture in the kingdom. He sent a circular letter with a questionnaire to lists of landowners and farmers drawn from his own past reports. By April most of the replies were received and "they describe such a state of agricultural misery and ruin as to be almost inconceivable." Young dreaded a scarcity of bread when multitudes were almost starving for want of employment. Country banks were ruined, he thought, by the Bank of England failing to issue enough money for circulation.

By 1816 Suffolk was also in a very depressed state. By 1816 the Guldhall Feoffees were completing the enclosure of land in Bury, and this may have helped to stir up further discontent. In April there was trouble in the countryside around Bury, and on the 29th April the Bury Magistrates issued a proclamation that they intended to enforce the law against disorderly assemblages, and "outrages". By May, violence reached Bury, when on the 8th large crowds gathered on the market, and on the 14th Robert Gooday's barns in Southgate Street were burned to the ground by a mob.

The less well off did not have any efficient way to look after their small savings. In 1797 Arthur Young had written that Box Clubs "flourish very considerably in Suffolk". These were little local savings clubs. In 1810 the Reverend Henry Duncan of Ruthwell, Dumfriesshire, launched a community self-help project that spread nation- and world-wide. He wanted to help his poorest parishioners save for times of hardship. He devised a scheme by which ordinary people could save their pennies and the Ruthwell Savings Bank was born. It was a resounding success, resulting in hundreds of towns and cities wanting to form their own savings banks. According to Hugh Paget a savings bank opened in Bury St Edmunds in 1816, but further details are scant. However, this Savings Bank would eventually prosper sufficiently to move into Savings Bank House adjacent to the Norman Tower, in 1846.

|

|

Clare Bank £1 note of 1819

|

|

1819

|

The Clare Bank had been opened by James Ray and his son, James Reynolds Ray, in 1801. James Ray was a grocer and draper in Clare who moved into banking like other prosperous merchants at the time. The Rays of Clare do not seem to have had any family link to the Rays of Bury St Edmunds, who were also in the drapery business. Ray's Bank was forced into bankruptcy following the theft of a large number of their banknotes in 1819. The closure of the Clare Bank was not only a financial blow to its owners, but also left people who held their banknotes unable to spend them, or convert them into cash.

The agricultural slump had already greatly affected the banks, as well as the agricultural communities they served. However, a branch of the Bury and Suffolk bank was soon opened in Clare, following the failure of Ray's Bank in that town.

|

|

Sparrow's Suffolk and Essex Bank

£10 note 1819 |

|

blank |

The Suffolk and Essex Bank at Sudbury now carried the partnership names of James G Sparrow, George Brown, John Fenn, Charles Hanbury, Joseph Savill and George Moor, as seen on this ten pound note dated 8th May, 1819.

|

|

Willett's Thetford Bank

£1 note of 1817

|

|

1822

|

Willetts Bank, called the Norfolk and Suffolk General Bank, closed down at Thetford, Brandon and Mildenhall, affected by the agricultural slump. Their branch in Bury which had opened in 1806 also closed.

In response the Bury and Suffolk Bank of the Oakes family opened a branch at Mildenhall, and possibly for a very short time in Brandon. The Oakes bank became Oakes and Co in 1822, when Oakes and son were joined in partnership by his grandson.

Highway robbery was still a hazard for the local family banks. The coach from London to Needham Market was robbed and Alexanders Bank of Needham lost £31,129. They had to issue new notes printed in red and told the public not to accept their old black printed notes. They paid out £5,000 in rewards and eventually managed to negotiate most of the money back via solicitors for the robbers!

Things were so bad in Bury that the first ball of the Bury Fair Season had to be cancelled as only 10 tickets were sold, compared to 409 a year earlier.

|

|

1825

|

December 1825 produced a financial crisis when a series of banks crashed nationwide. Luckily there was only one bank failure in Suffolk, and this was at Brandon. Most could get to London to get cash to meet demands, and none had London bankers that failed. Sparrows of Braintree were not so fortunate.

Sparrow withdrew from his Suffolk and Essex Bank at Bury, which was now styled Brown, Hanbury and Bevan.

|

|

Stowmarket Bank £5 note of 1826

|

|

1826

|

This banknote is dated 6th December, 1826, issued by the Stowmarket Bank. Partners listed on it at this time were Brown, Bevan, Prentice, Moore and Hanbury. Fenn's name has been crossed through on this issue. This bank had been founded in 1795 by Crowe, Sparrow and Brown.

To address the issue of the failure of small banks the Government allowed the formation of Joint Stock Banks, which allowed the pooling of many sources of capital by way of shares which in turn produced larger, better capitalised banks.

However, many of the old small local partnerships continued in business until about 1900.

|

|

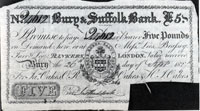

Oakes Bank £5 note of 1827

|

|

1827

|

This five pound note was issued at Bury St Edmunds by the Oakes Bank. Now called the Bury and Suffolk Bank the partners since 1822 had been James Oakes, Orbell Ray Oakes and H J Oakes. As was normal practice at the time, the banknote was cancelled after it was cashed and this is carried out by cutting off the issueing cashiers signature.

Oakes's favourite oak tree remains on the note but is now contained within a mock heraldic cartouche with the motto Quercus Robur Salus Patrie. Quercus Robur is the latin name for the Oak tree.

(Notes which survive fully intact normally indicates that they were proved in bankruptcy proceedings.)

|

|

1829

|

James Oakes, the prominent banker of Bury St Edmunds, died but he left a diary covering the years from 1778 to 1827. He had been five times Alderman of the town, Deputy Lieutenant of Suffolk, Justice of the Peace, Turnpike Trustee for Thetford and Sudbury roads, a Guildhall Feoffee and governor of King Edward VI Grammar School.

To strengthen the Oakes bank two new partners were admitted; Robert Bevan and David Hanbury. Their notes now included the heading Oakes, Bevan and Hanbury. In effect this caused the amalgamation of the Suffolk and Essex bank of Brown, Bevan, Moor and Hanbury with Oakes Bank.

|

|

1830

|

The year 1830 saw some consolidation of banking in Suffolk. Sparrow had been forced to withdraw from his Suffolk interests because of financial difficulties, probably caused by him being overstretched by involvement in too many businesses. This had led to Oakes, Bevan and Co's absorbing the Suffolk and Essex Bank of Bury and Stowmarket, and also the Fenn and Addison Bank at Sudbury.

The Oakes Bank partnership now included Mr George Moor from Bury's Suffolk and Essex bank and their Stowmarket Bank.

Oakes Bank now became known as Oakes, Bevan, Moor and Hanbury, and the bank took a larger share of the banking business of West Suffolk. This bank would survive until 1900 when it would be taken over by the Capital and Counties Bank, eventually joining Lloyds Bank.

In 1830 Pigot's published their first Directory of Suffolk. This listed each town in the County, describing their history, local gentry and professions, and their tradesmen.

Bankers recorded were as follows:

- Oakes, Bevan, Moore and Hanbury, 9 Butter Market

- Edmund Squire, 11 Great Market Place-

(Both draw on Barclay Tritton and Co. London)

Nothing much seems to be known about Edmund Squire's banking business but he had been in business since 1794, combining it with his wine selling business.

|

|

Nowton Court

|

|

1832

|

James Oakes, the Bury banker, local public figure and political fixer, had died in 1829.

His son, Orbell Oakes, bought the manor of Nowton and retired there to become a gentleman farmer and antiquarian.

He had amalgamated the family's Bury and Suffolk Bank with Browne, Bevan and company to produce Oakes Bevan and co.. The family would retain an interest in the bank until 1899 when it was bought by the Capital and Counties Bank. Orbell continued his involvement in local affairs, perhaps more so than in his business affairs.

|

|

1835

|

Edmund Squire died in 1835, but his wine business and his banking business were both purchased by Charles Le Blanc. By 1839 Le Blanc would take John Worlledge in as a partner.

|

|

1839

|

Charles Le Blanc's banking business was now named Worlledge and Le Blanc. In 1839 they opened a branch in Mildenhall.

|

|

1840

|

The Oakes bank now carried the names of Oakes, Bevan, Moore and Bevan on its cheques and banknotes.

|

|

Stowmarket Bank £5 note of 1841

|

|

1841

|

The Stowmarket Bank of Brown Bevan and Co was amalgamated with the Oakes Bank of Bury St Edmunds in 1830. It remained as an independent functioning bank but after 1840 its notes carried the names of Henry James Oakes, Robert Bevan, George Moor and Wm R Bevan. In 1861 extensive fraud was discovered and this bank came under the direct control of one of the Bury partners.

|

|

1844

|

An Act of Parliament in 1844 prohibited any new banks from issuing their own banknotes. Existing banks could only issue such notes as they already had in circulation by 1844. In addition no bank within 65 miles of London could issue its own notes which all had to be replaced by Bank of England notes.

In 1844 William White published his "History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk".

Bankers recorded at Bury St Edmunds were:-

- National Provincial Bank of England in the Meat Market

- Oakes, Bevan Moore and Bevan, Bury and Suffolk Bank, 9 Buttermarket

- Suffolk Banking Co at 10 Meat Market

- Worledge and LeBlanc at 11 Meat Market

- Savings Bank in the Guildhall, open Saturday 12 till 1

|

|

1845

|

By 1845 John Worlledge was the sole proprietor of the bank previously known as Worlledge and Le Blanc. He would take in his son, also called John, as a partner and also Thomas White Cooper.

This bank soon became known as Worlledge and Cooper until 1862.

|

|

The Savings Bank |

|

1846

|

The Norman Tower was restored in 1846 and 1847. The houses built against each side, and even partly in front of it, had been taken down in 1845. Some five or six feet of earth which had accumulated over centuries was excavated from around the foot of the tower, to leave its base exposed in the intriguing way in which it remains today. This accumulation of earth is thought to have been a deliberate attempt to raise the ground level to avoid flooding in late Medieval times. On the tower the walls were strengthened with iron bolts, and the foundations underpinned with concrete. As part of the reinstatement process the Savings Bank built and opened new premises next to the Norman Tower, and these still stand today. The date "1846" is picked out in the brickwork of the Bank on the chimney wall facing the Norman Tower. This Savings Bank was often erroneously called the Penny Bank and it closed as a bank in 1892.

The architect of the Savings Bank, together with much of the restoration planning around the Norman Tower, was Lewis Nockalls Cottingham, who was born in Suffolk. In 1841 he had worked on the parish church in Horringer, and from 1842 to 1847 was responsible for restorations at St Mary's church in Bury St Edmunds.

|

|

1847

|

The Bury and Norwich Post of 2th September 1847 carried an announcement from the:

"Savings' Bank, Bury St Edmunds. Notice is hereby given that the business of the above institution will in future be carried on in the Banking Rooms recently erected next the Norman Tower. William Williams, Thomas Reach, Clerks. Bury St Edmunds September 26th, 1847."

|

|

Unissued Oakes Bank

£5 note of 1850s

|

|

1854

|

The Oakes Bank again traded under the names of Oakes, Bevan and Co. until 1895.

|

|

Worlledge Bank Cheque

Dated 1855 signed John Worlledge

|

|

1855

|

In 1839 Le Blancs Bank became Worlledge and Le Blanc at 11 Meat Market.

In 1845 it became Worlledge, son and Thomas Cooper. This cheque is styled Worlledge and Co, and was issued in 1855. John Worlledge lived at Ruffins, in Chevington, and this cheque was issued by him at his home, as shown in the date section.

|

|

Worlledge Bank Cheque

Dated 1862 signed Peter Huddleston

|

|

1862

|

Worlledge's bank at Bury St Edmunds became called Worlledge, Huddlestone, Cooper & Co from 1862. Peter Huddleston lived at Little Haugh Hall in Norton, and is described in Whites Directory 1855 as Huddleston, Peter, Esq, Little Haugh Hall, with out any occupation listed.

By 1862 he was a banker and this cheque was issued by him, from his home at Norton, as shown in the date, "Norton July the 7th 1862."

|

|

1864

|

The owner of Ousden Hall and manor, Thomas Ireland, had died in 1863, and in 1864 the whole property was put on the market, together with its 2,350 acres in Ousden and adjoining parishes. The property was bought by Bulkley John Mackworth-Praed, a member of the Praed banking family. (Praed's Bank later became incorporated into Lloyds Bank.) The family seem never to have lived at Ousden, and the property was let, primarily for its attractions as a shooting estate.

When Bulkley died in 1876, his son, Sir Herbert Mackworth-Praed, continued to let the estate. Sir Herbert was MP for Ipswich, as well as a banker. Eventually the property would be bought to live in by Algernon Mackworth Praed, in 1913.

|

|

1866

|

Worledge's son John left his bank in 1866. New partners were taken on, the most well known being Edward Greene. Also taken on were Machell Smith, Peter Huddleston, and Jervais Huddleston.

From 1866 this bank became known as Huddleston, Cooper, Greene and Co..

The Bury St Edmunds Building Society was founded in 1866. In those days, a Building Society meant what it said. A group of people set up a mutual society to help each other build their own homes. This society bought an orchard off St Johns Street to be sold in 57 plots to its members. Each plot had to have a house built on it of a value not less than £110. Orchard Street remains a fine residential road today.

|

|

1868

|

The National Provincial Bank was built in Italianate style in Abbeygate Street, Bury. Today it is the Alliance and Leicester.

|

|

1873

|

Huddleston, Cooper, Greene and Co. became Huddleston, Greene and Co.. The wine business, first started by William Dalton, was still part of the overall business of the firm.

|

|

1878

|

The Bury bank of Huddleston and Company was bought by Gurney's Bank of Norwich, in 1878, together with Huddleston's branch at Mildenhall, in existence since 1839. Gurney's Bank would, in turn, become part of Barclay's bank in 1896.

The wine business, first started by William Dalton, was sold to Hunter and Oliver.

|

|

1881

|

Barclay's Bank opened its three storey premises in 1881, at the top of Abbeygate Street in Bury. For a few years it incorporated the Post and Sorting Office until 1895. In 1861 the post office in Bury was at 10 the Buttermarket, and customers stood outdoors and handed in letters or bought stamps through a foot square window. A few years later it moved to 24 Abbeygate Street, on the corner of Lower Baxter Street, where customers could be accommodated in a proper indoor office. In 1881 there was a need for larger premises, so the Post Office moved to 52 Abbeygate Street, premises formerly used by Gurney's Bank who had moved next door. The next move would wait until 1895, when the present post office on the Cornhill was built.

|

|

1892

|

The Savings Bank, located alongside the Norman Tower, closed its doors as a bank in 1892. Although often referred to as the Penny bank, it was properly called the Savings Bank.

|

|

Gurneys bank cheque of 1894

|

|

1894

|

This cheque shows the names of the partners in the Gurneys bank at this time were Gurneys, Birkbecks, Barclay and Buxton. Gurneys of Norwich had come to Bury by buying out the Huddleston Bank in 1878.

|

|

Oakes, Bevan, Tollemache & Co

Cheque dated 1898

|

|

1895

|

The Oakes Bank found a shrinkage in their business with increased competition from larger rivals. To obtain extra capital it took on M G Tollemache as a partner. He was soon joined by his brother D A Tollemache, lately a partner in the Ipswich bank of Bacon, Cobbold and Co..

|

|

1896

|

In July of 1896 the banking company of Barclay, Bevan, Barclay and Tritton joined 19 other private banking businesses to form Barclay & Company Limited, a joint stock bank, with 182 branches and deposits of £26m. The Gurney's Bank, in its various guises throughout East Anglia, including Bury St Edmunds, joined this new company.

The Oakes bank soldiered on as an independent bank for three more years.

|

|

1899

|

The old local families bank of Oakes, Bevan and company was sold to the Capital and Counties Bank.

|

|

1914

|

The Midland Bank opened in premises at the top of Abbeygate Street in Bury.

|

|

Lloyds Bank Sign

|

|

1918

|

The old Bury St Edmunds banking firm of Oakes, Bevan and Co had been taken over by the London based Capital and Counties bank in 1899.

In 1918, the Capital and Counties Bank in Bury became a branch of Lloyd's Bank, and remains so today. The building still stands on the Butter Market, where it was built in 1795 to 1797 as Spink and Carss Bank. From 1829 to 1899 it had been Oakes and Bevan's Bank, before becoming Capital and Counties in 1899.

This local Lloyds bank sign has always provoked interest because it does not feature the Black Horse, which Lloyd's had been using around this time. However, the old Birmingham roots of Lloyds Bank, originally dating to 1765, and styled Lloyd and Taylor, had employed the beehive as its symbol. Both the black horse and beehive were used together by Lloyds Bank until the 1920s. The black horse originated from John Bland Goldsmiths, (1728) which itself became Barnetts Hoares and Co, bankers, and was taken over by Lloyds in 1884. The sign we see in the Buttermarket today has retained Oakes's Oak tree. Margaret Statham has stated that the beehive was also a symbol once used by the Bevan family. The beehive was in general use as a symbol of industry and thrift. The two pineapples remain unexplained at present, although they are generally used as a symbol of welcome, hospitality and friendliness.

|

|

1931

|

Britain had gone back on to the Gold Standard in 1925, but on 21st September, 1931, the government had to abandon it, and the value of the pound fell to about 16/-, a drop of 20% against currencies still on the gold standard. It was thought that this would make imported food more expensive, allowing British farmers to compete, and increase output.

But land values and land rents continued to fall under the impact of cheaper foreign food imports. Only new ideas like growing sugar beet, or fruit and roses at Wickhambrook, or Lucerne at Elveden, or poultry and egg production, stopped the farming industry from a total collapse.

|

Prepared for the St Edmundsbury history project

by David Addy, 20th November, 2020

Books consulted:

The Banknote Yearbook

"Early East Anglian Banks and Bankers" by Harold Preston, 1994

Specimens:

The specimens shown are from Moyse's Hall and private collections.

|