The Anglian Glaciation |

The River Lark

Up to the year 1600

|

474,000 BP

|

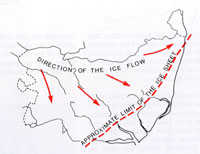

The Anglian Glacial epoch began around 474,000 years ago, and probably lasted to about 427,000 BP. This was the biggest of all the glaciations as far as the UK is concerned.

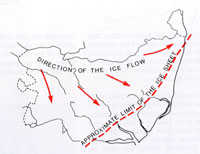

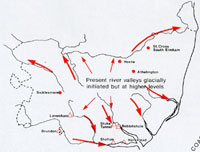

This glaciation arrived from the north-west and the ice sheet reached the coast south of Lowestoft and aligned itself roughly from there to Ipswich at its edge. It also covered the Midlands and reached south of Essex. The River Thames was pushed nearly 100 miles south to somewhere near its modern course.

The Anglian ice sheet covered all of Suffolk except perhaps for the very south east. Suffolk was never again completely covered by ice in later ice ages.

|

|

Post Anglian Interglacial sites |

|

427,000 BP

|

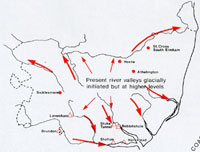

Rivers created by melting glaciers flowed across East Anglia. One such system crossed today's Elveden and Barnham areas, and considerable stratified evidence has survived the jumbling up process often caused by glaciations.

When the ice melted it left behind our boulder clays and the melt water carved out the estuaries of the Waveney, Deben, Gipping and Stour. Typical deposits include the Lowestoft Till found at the lower levels of Elveden Brickyard Pit.

The Anglian Ice Age had largely receded by 427,000 years ago, and the Hoxnian Interglacial, or warmer period began and lasted until about 364,000 BP.

|

|

200,000 BP

|

In the area now called Suffolk, the climate was warmer than it is today during this time called The Middle Paleolithic Period. Mammoths roamed the land, along with herds of bison and horses. The Straight Tusked Elephant was also in Suffolk at this time. Along with the remains of the animals are the flint tools left by the Neanderthal inhabitants of Suffolk .

|

|

70,000 BP

|

The Devensian cooler period began around this time. In the advance of the ice sheet down from the north, the ice may again have reached the North Norfolk coast. The ice probably advanced and retreated sporadically, but did not seem to reach its peak until around the period from 24,000 BP to 15,000 BP. Drainage systems must have been disrupted several times.

|

|

Woolly Mammoths |

|

30,000 BP

|

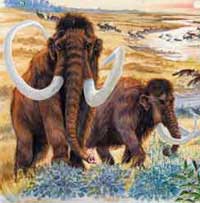

In Suffolk at this time the climate was cold, with a landscape similar to that of the arctic regions today. Suffolk was now inhabited by the Woolly Mammoth, his coat necessary in the prevailing cold conditions. Also present were the Woolly Rhinocerous, bison and Reindeer. Wolves and Hyaenas preyed on the herds, as did the homo sapiens, our own ancestors, who would have been here following the herds.

The Woolly Mammoth had a fatty hump as well as his thick coat. It had had small ears against the cold, compared to our modern elephants. Long curved tusks are thought to have been used to sweep snow off the ground to expose plant food. Remains of these giants are commonly found in in the gravel extractions of the Gipping, Stour, Lark and Waveney Valleys.

|

|

Extent of Devensian Icesheet |

|

24,000 BP

|

From 24,000 BP until 18,000 BP, the Devensian Ice Age was at its peak. This final glaciation reached into North Norfolk. Sea level was about 60 metres below present levels, and there was a dry land bridge between Suffolk and the Low Countries and Denmark.

|

|

6,500 BC

|

In the Late Mesolithic period, around this date the sea rose as the ice caps melted and retreated and Britain became an island when the sea broke through. The Suffolk coastline was several kilometres east of where it is now. Remnants of ancient forests drowned by sea level rises can still be seen today. At places like Titchwell and Sea Palling in Norfolk soft spongy remains of tree roots are often visible at low tide. Trees survived here above the water line perhaps up to 2,500 BC, as water levels gradually rose. Sites thought to date from the Late Mesolithic include Wangford, Lakenheath and West Stow.

|

|

2,500 BC

|

Britain was cut off from the continent by about 6,500 or 6,400 BC, but the sea level did not immediately rise to the level that it is today. Forests continued to grow in areas now below the sea until about 2,500 BC.

Remnants of ancient forests drowned by sea level rises can still be seen today. At places like Titchwell and Sea Palling in Norfolk soft spongy remains of tree roots are often visible at low tide. Trees survived here above the water line perhaps up to 2,500 BC, as water levels gradually rose.

|

|

Two tribes meet in Suffolk

|

|

100 BC

|

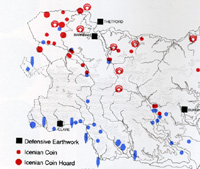

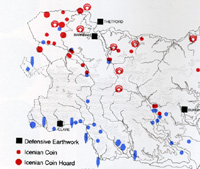

It is thought that there were two separate peoples in Suffolk at this period, with a boundary roughly from Newmarket to Stowmarket and Aldburgh. To the north were the Iceni, and in the south the Trinovantes. Their names are known from Roman writers. The iron age Iceni tribal heartlands were in North West Suffolk around Ixworth and the Blackbourne Valley and Icklingham, West Stow and the Lark Valley.

|

|

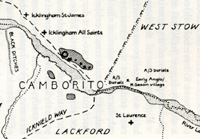

Camborito at Icklingham

|

|

100 AD

|

By the end of the 1st century there were six small "Roman" towns in Suffolk. Their inhabitants would have been largely the native inhabitants, but with officials answerable to the Roman Empire, and a smattering of peoples from across the countries of the Empire. Administration of the area was probably from either Venta Icenorum, (Caister by Norwich), or Colchester.

Most, if not all, of these towns would have been existing settlements of the existing celtic tribes.

The six towns, from west to east, were:

- Icklingham

- Long Melford

- Pakenham

- Coddenham

- Scole

- Hacheston

|

|

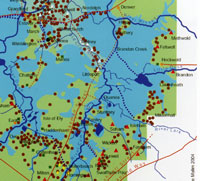

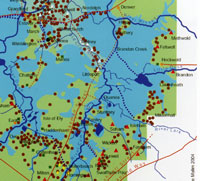

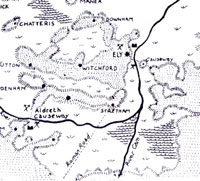

The Fens in Roman times

The Fens in Roman times

|

|

140 AD

|

During the time of the Emperors Hadrian and Antony, from 120 to 140, much of the infrastructure of the Roman Fens was put in place. On the River Lark a canal was built from Isleham to Prickwillow. This was probably to ship out clunch as a building material from Clunch Pits at Isleham. No doubt it also served to improve local drainage as well.

The map shows an intensive cluster of settlements along the fenland edge, indicating a prosperity and activity which has not been fully recognised in the past. The Fenland edge was a hive of activity in Roman times, with trading boats coming and going, industrial workshops and settlements supported by the rich natural resources of fish and game available from the waters. Summer grazing was widespread on the water meadows, and thatching reeds were widely available.

Hockwold in particular became an important port in the area.

|

|

Roman Barnack stone coffin

|

|

250 AD

|

This stone coffin was removed from the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at West Stow. It is believed that it was recovered from a Roman burial associated with an earlier period at nearby Icklingham. It is made of limestone from the Barnack Quarries and probably transported to Icklingham via the Fenland waterways and rivers, and then up the River Lark to Icklingham.

Oolitic Lincolnshire limestone, including some called "Barnack rag", was a valuable building stone first used by the Romans. Much later, quarrying continued in the Middle Ages when the abbeys at Peterborough, Crowland, Ramsey, Sawtry and Bury St Edmunds all used Barnack stone. Blocks of stone were transported on sleds to the river Welland and loaded on to barges on which they were taken down the River Nene and the Fenland waterways.

|

|

Lead cistern with Chi-rho, Icklingham

|

|

314 AD

|

By the 4th Century Britain was becoming Christian with an organised church with bishops; three went to the Council of Arles in 314. A Christian church has been found at Icklingham with a baptistry and cemetery. Four lead tanks, possibly fonts, were found in 1974, with Christian symbols of chi-rho, alpha and omega.

|

|

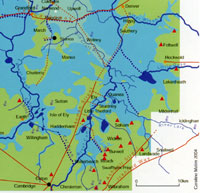

Fens in late Roman times

Fens in late Roman times

|

|

350 AD

|

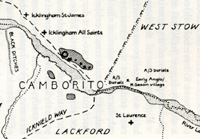

By late Roman times the settlements which were successful had expanded. In West Suffolk the development of Camborito at Icklingham probably indicates a west facing town, with its lines of communication concentrated on the waterways of the fens. The fenland edge continued to be a centre of Roman prosperity in Suffolk.

|

|

Great dish from Mildenhall Treasure

|

|

360 AD

|

In 1942 a hoard of 34 silver objects dating from this period was ploughed up in a field off the A1101 at West Row, near Mildenhall. In 1946 it was declared Treasure Trove and acquired by the British Museum. The remains of a fourth century Roman building was found about 30 yards away.

|

|

410

|

In the year 410, the cities of Britain were officially ordered by the Emperor Honorius to take responsibility for their own defences. In the same year the Goths took Rome and an important result of the collapse of central Roman rule was that no further coinage was imported into Britain. In addition, no new coins seem to have been minted in England from 411 to about 630.

It was the beginning of the end - administrators, specialists and the military could not be supported by money. There was no money to pay for the infrastructure of roads and canals to be maintained. The drainage works in the Fens were largely abandoned over the next few years.

From 410 to 442, Britain was independent from Rome, and this was the last age of Roman Britain before the Saxons were to effectively take over.

|

|

430

|

After a short time the number of Saxons allowed to settle increased and new areas were penetrated. Very early remains have been found at Caistor by Norwich, Luton and Abingdon. These were strategic settlements, to protect the Cotswold heartlands, and Norfolk was particularly well settled. Because the north still had the army, there was less need for reinforcements to be sent there. Forces were placed to protect the North road, the Thames estuary and the major intersections of the Icknield Way. These inland posts were really a defence line of last resort.

One of these posts might have been at West Stow, sitting on the River Lark crossing of the Icknield Way.

A sprawling half mile long Romano-British settlement possibly known as Camborito had been long established at adjacent Icklingham, and a Roman villa has also been identified there. Finds have been made here over many years and four lead water tanks have now been discovered in Icklingham bearing Christian symbols. In 1974 an apparently Christian cemetery was found with a possible Christian chapel.

Around this time it appears that the Anglo-Saxon village Stowa was first established just the other side of the Icknield Way from Camborito. Exactly how they interacted and how relations changed over the next 50 years we do not know. The Romano-British were Christian at this time and the Anglo-Saxons were pagans.

|

|

Anglo Saxon 'keel' |

|

442

|

More and more boats were arriving from the Continent. There was pressure on the Saxon's homelands from new settlers from Denmark and Holstein, and flooding from the rising sea levels. One such boat, constructed of larchwood, was found buried at Ashby Dell in Suffolk in 1830, a few miles from Burgh Castle. It may have arrived there at a time when the valley was actually a waterway, for sealevel was rising during the 5th century. Its construction is similar to the Nydam boat, excavated in Denmark. A reproduction of the Nydam vessel is shown here.

Using such boats they may have been able to penetrate into the Wash, up the Great Ouse and into the River Lark.

|

|

Anglo Saxon Village |

|

460

|

The Lark, Blackbourne and Ouse valleys of West Suffolk had been settled by these mixed Angles, Saxons and Friesians by this time, including at West Stow.

The village of Stowa, as we call it today, was located on a small hillock by the River Lark, on very light sandy soil. The Icknield Way crossed the River Lark at a ford a few yards away, running roughly north and southwards. An old Roman road ran east and westwards a few yards north of the village. This road led to the old Romano British village of Camborito, just a few hundred yards to the west. The village cemetery was just across the Roman road.

The Central Suffolk clay soils do not seem to have attracted the Anglo-Saxons. They preferred the river valleys, and more easily worked soils. Other settlements have been excavated at Honington and Grimstone End in Pakenham. We do not know exactly when Bury l was first settled by Anglo-Saxons, but we have a better idea of where it took place. In modern Bury we have evidence of several Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, so there were probably at least four small villages within the area of today's town. One was probably where the Abbey's ruins remain today, one near Barons Road, one at Westgarth Gardens and one near Northumberland Avenue.

It seems that the settlers in West Suffolk were based along the river valleys which flowed into the Fens, and that they looked to trade in that direction rather than to the east. It seems likely that West suffolk was thus settled from the direction of the Wash, through the Fens, while East Suffolk was settled up the river valleys like the Gipping, Stour and Waveney, which all flowed eastwards towards the North Sea.

|

|

Gold pendant from Undley |

|

500

|

By now the war in England had been fought to a standstill, with partition of territory being an established fact. Eastern England, and East Anglia in particular, was firmly held in Saxon and Angle hands. At Undley, near Lakenheath, a high status Angle wore this gold pendant shown here. It was made in the late 5th century in Schleswig or southern Scandinavia. A roman helmeted head copies many Roman coins, and although the wolf and infants is a strong Roman motif, there are also runic characters present.

Although the British had stemmed the English advance further westwards, the Roman Empire had faded around them, and they had no larger continental Empire to support them. The Romanised economy was destroyed by war, and the British had to rebuild their lives in their own way, with only half the country's resources available to them.

In the Fens the Roman drainage system built around Car Dyke had failed as there was no administration to maintain it against the rising sea levels. Areas of Fen now flooded, leaving only Ely and a few other islands above the water level. Along with this problem came a rise in sea levels through the 4th and 5th centuries, so that by this time East Anglia was a virtual isthmus, cut off from the area of Mercia to the West by the great marshy fenland.

|

|

Anglo Saxon horse burial |

|

550

|

Around 550 a Saxon nobleman was buried with his horse at Eriswell. The site was discovered in 1997 under a baseball pitch scheduled for redevelopment on the USAF base at RAF Lakenheath. Some 200 graves were located on the site, spanning a period of 150 years. This is now a completely different form of burial than the earlier cremations exemplified at West Stow.

Over the next 5 years more graves were discovered. Eriswell had three cemeteries with 446 graves finally identified. This is a major find for East Anglia and covers the late 5th to early 7th centuries. There were other horse burials found, but the first one in 1997 aroused the most excitement.

|

|

Defensive dykes on Icknield Way |

|

c.575

|

The Devil's Dyke at Newmarket, and the Fleam Dyke, a few miles further to its south west have long been believed by some historians to date from around this time to defend from attack from the west. Recent detailed work has confirmed that these earthworks date from the 5th to the 7th centuries. They are also aligned to face an attack from the south west.

|

|

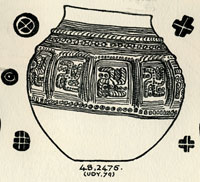

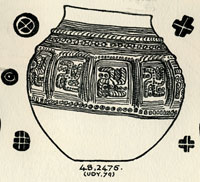

Lackford Cremation Urn & potmarks

|

|

585

|

In 1947 T C Lethbridge excavated a pagan Saxon cemetery at Mill Heath, Lackford. The site is above the 50 foot contour on a peninsula of land between the south bank of the River Lark and a the Cavenham Mill stream. He found between 400 and 500 cremation urns, a concentration which is unusual for the Lark Valley, where earth burials, or inhumations, are more prevalent. There were swastikas present upon a number of cremation urns, and the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Lackford has yielded some of the most exquisite designs of this image.

|

|

635

|

In his later years Sigeberht was reported by Bede, to have handed over all his authority in East Anglia to King Egric, probably the man known to other historians as Aethelric. Aethelric had already been ruling over part of the territory of East Anglia in a joint arrangement with Sigeberht.

Sigeberht himself thus appears to have been the first English king to abdicate. His reason was in order to become a monk.

Around 635, Sigeberht had founded a monastery at Bedericsworth, today called Bury St Edmunds. Bede states that he built the monastery for his own use. It was one of the earliest schools of English literacy, but it was not the type of structure whose ruins we see today, but was probably made of wood. The site may have been very close to the later abbey site at Bury. Bede recorded that Sigeberht now retired to live in his monastery. A marginal note made in the 12th century book, the Liber Eliensis, is the only evidence we have which identifies its location as Bury. He entrusted his earthly kingdom to his kinsman, Egric, (or Aethelric), who had already governed part of the kingdom , and "devoted his energies to winning an everlasting Kingdom".

Both Ipswich ware and Thetford ware have been excavated from the site of the Bury monastery, indicating an occupation here between the 7th and 9th centuries.

Why would Sigeberht have chosen this location at Bedericesworth? Did the Wuffing royal family perhaps own, or have rights over, land in the area? Did a relative already live on the site? Or was it a site of wilderness and marsh, peopled with demons and spirits, sorely in need of a holy presence?

The site was bounded by the River Linnet to the South, the River Lark to the east and the marshes of Tay Fen to the north. In reality it was probably surrounded by marshy pools and waterways, and quite isolated. As far as we know the Romans had failed to be attracted to Bury, and by this time there were a few anglo-saxon villages occupying the river banks in the area nowadays covered by the town. It was a good place to seek isolation, far from the royal court at Rendlesham, but safely inside the Wuffing kingdom.

With an abdicated king in residence, this would have been the start of the settlement as a villa regia or royal town. Over the years it was possibly able to acquire such rights as holding a market, but more importantly, charging market tolls.

Eventually the rivers may well have been used to transport some goods to and from the small market.

|

|

650

|

The title of middle Saxon Period is assigned to the period from c.650 to c.850, when Christianity was being adopted by the formerly pagan Saxons. Other names for this time are Early Medieval or Christian-Saxon.

The West Stow Anglo Saxon Village site was deserted at about this time, but possibly moved to the location of the current West Stow village, around a Christian church and cemetery. There is evidence that other pagan Saxon settlements in Suffolk were abandoned at around this time, possibly to make a clean start on a new Christian site.

During the Middle Saxon period the Fens and the clay soils were settled once again so that by the 9th Century most of our villages had been founded. However, we need to remember that the sites of named villages may have moved over time since then.

|

|

St Etheldreda of Ely

|

|

673

|

Aethelthryth, the wife of King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, had determined to live a monastic life, and had been in a monastery near Berwick for about a year. In 673 she fled from Northumbria, pursued by soldiers, to return to her own estate at Ely.

She founded a double monastery at Ely, one part of which has been claimed to be the first nunnery in the country. Later she was to become known as one of the most famous saints of Anglo-Saxon England. Some time after about 696, St Audrey was venerated as a saint and became the greatest woman-saint of East Anglia. Her shrine in Ely attracted pilgrims from far and wide.

|

|

835

|

Since 793 the Vikings had sporadically raided Irish and Continental coasts but in, and after, 835 many more hit and run raids were carried out on England, up to 15 miles inland. Danes mainly raided Southern England, and the Norsemen attacked the North, even establishing a capital at York, but these were part of a much bigger expansionist movement which also reached Iceland and North America, Russia and Spain.

|

|

841

|

Viking raiding parties hit Lindsey, East Anglia and Kent. Others landed at Dublin, and Rouen was sacked. The Chronicles say that many men were slain by the assault of the host on East Anglia.

Ipswich and Norwich may have been targets for these attacks in East Anglia. All of the coastal monasteries like Dommoc and Iken, with their valuable trappings donated by the faithful, must have been vulnerable, and too numerous to be properly defended when attack came from out of the blue.

|

851

|

For the first time the Vikings had over-wintered in England. By the end of winter they had gathered 350 ships and up to 6,000 men to launch a major attack up the River Thames. They 'ruined Canterbury', and attacked London, causing great carnage and putting King Beorhtwulf of Mercia to flight.

|

|

865

|

Modern historians refer to the 200 year period after 865 as The Late Anglo-Saxon time. This is because the year 865 heralded disaster for Anglo-Saxon England. It was the year of full scale invasion by the Great Army of the Danes.

|

|

869

|

From York the Great Army of the Danes marched back into East Anglia, but this time they attacked Thetford. Thetford stood on the Icknield Way, at an important crossing point of the Rivers Little Ouse and Thet. The town could be reached not only by the army on horseback but, most importantly, their ships could reach Thetford by sailing into the Wash and then following the rivers through the Fens.

" The Danish took the victory and killed the king and conquered all that land, and did for all the monasteries to which they came. At the same time they came to Medeshamstede (Peterborough) : burned and demolished, killed abbot and monks, and all that they found there, brought it about so that what was earlier very rich was as it were nothing."

The Danes also attacked Crowland Abbey in the Fens, and burned it down. Other monasteries assumed to have been destroyed around this time include Beodericsworth at Bury St Edmunds, Ely and Soham. Iken, Brandon and Burrow Hill were deserted, and may well have already been destroyed in the earliest attacks. Dommoc disappeared so completely that we are still debating its exact location.

The town of Thetford seems to have been attractive to these invaders as a base in East Anglia. They could bring their longboats up the Wash and follow rivers into the Little Ouse, and on to Thetford. Thetford also had ancient iron age earthworks which could be pressed into service as a camp and horse stockade. Thetford was certainly revived in importance from these beginnings as a Danish winter stronghold. For the next fifty years, East Anglia was under viking control.

|

|

|

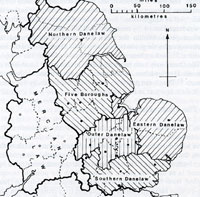

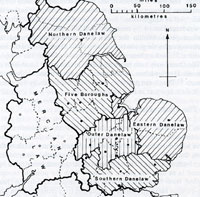

The Danelaw |

|

879

|

Danish settlement began in earnest following the peace treaty which had given them control over the North and East of England. Because Danish law was applied in these areas they were known as the Danelaw. East Anglia became the Eastern Danelaw, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded the Danish settlement there:

"Here the raiding army went from Cirencester into East Anglia, and settled that land and divided it up".

In many ways the Danelaw, including East Anglia, now became like a Danish province. Old allegiances to local lords were weakened. Before the Danes, land could only be transferred by the King's charter. Viking law allowed it to be bought and sold in front of witnesses, at least in the chief towns of Cambridge, Thetford, Ipswich and Norwich. Streets like Colgate and Fishergate in Norwich took their names from the Danish 'gata', meaning street. York became a Viking capital, and its well known Coppergate derives from this time.

The Suffolk town of Beccles is particularly well endowed with 'gate' street names. These include Ballygate, Becclesgate, Blyburgate, Hungate, Ingate, Newgate, Northgate, Saltgate, Sheepgate and Smallgate.

|

|

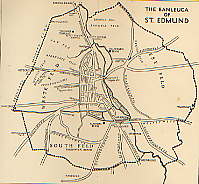

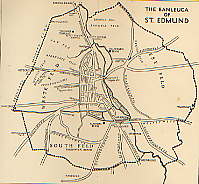

Banleuca Boundaries by C R Hart

|

|

945

|

According to an Anglo-Saxon Charter, in 945 King Edmund gave up his royal rights to taxes and all feudal dues and fees in the area of Bury St Edmunds for about one mile around St Edmund's shrine.

|

|

981

|

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle recorded attacks by pirate hosts from the north on Southampton, Thanet and Cheshire. Although there is no mention of attacks on East Anglia, Dr Lucy Marten has suggested that these almost certainly did take place each year after 980. The east coast was readily accessible to the Danes, and news from East Anglia was not usually reported in the Chronicles written far away in Wessex.

|

|

991

|

By 990 a version of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle has survived from London. This recorded more news from East Anglia and it would seem that suddenly a second wave of Danish attacks assailed East Anglia. In reality it seems likely that raids had been going on here since 980, but had not been recorded in the Wessex Chronicles.

|

|

997

|

From 997 to 1014 viking raids occurred every year.

By this time Norwich was catching up with Thetford as the main city of the Norfolk area. It had better access to the sea than Thetford and could handle more trade more cheaply because of this advantage.

|

|

1014

|

On 28th September, 1014, a natural disaster occurred when "that great sea flood came widely throughout this country, and ran further inland than it ever did before, and drowned many settlements, and a countless number of human beings." Low lying settlements in the Fens and the Broads areas were especially vulnerable, just as they still are today.

|

|

1016

|

After the Battle of Assendun, King Cnut followed King Edmund into Gloucestershire. Ealdorman Eadric and the councillors now tried to broker a peace between the two kings, and the kings agreed to meet at Ola's Island in the River Severn. It was agreed that King Edmund kept Wessex and the land south of the Thames, and the rest went to King Cnut. The Danish raiding army was paid off, and their ships went to London.

King Edmund Ironside died on 30th November, St Andrews Day, within a month of the Battle of Ashingdon, and so Cnut received all the kingdom. He was the first Danish King of all England, and was 23 years old. He was the famous King Canute, who was so upset by the constant praise of his court, that he is said to have demonstrated that he could not hold back the tides.

King Cnut or Canute, was descended from a long line of Danes who had caused great misery in England. One of his ancestors was Ivar the Boneless, who had killed St Edmund. He was the son of King Sweyn Forkbeard who had died suddenly (so it was said), after threatening to sack St Edmund's town. St Edmund must have hovered in the background of Cnut's mind as a saint not to be trifled with.

East Anglia, and indeed all England, was now once more under Danish rule and was to remain part of a large Scandinavian empire until 1042.

|

|

King Cnut or Canute

|

|

1020

|

To appease the Bishop, the dozen secular priests, or clerks, at Bedericsworth were sacked, but the Bishop did not get control of the shrine. King Cnut arranged for the building of a rotunda to the church of St Mary at Bury. Bishop Ailfric of Elmham then granted the monastery freedom from episcopal control and replaced the secular priests guarding the shrine by 20 Benedictine monks, 13 from St Benet Hulme in the Broads near Norwich and 7 from Ely. The Benedictines were financially and spiritually independent of the Bishop. Uvius, the Prior of St Benet's, was made the first Abbot of St Edmundsbury.

|

|

1014

|

Queen Emma now held the Eight and a Half hundreds of West Suffolk, and set herself up in the 12 carucate Manor of Mildenhall, a large and prosperous estate. From here she controlled the patronage of St Edmund, and seems to have also been a patron of the whole of East Anglia. In practice she had all the privileges of the Earldom, as well as the specific control of the Eight and a Half Hundreds.

|

|

1042

|

Danish rule finally ended when Harthacnut collapsed and died "as he stood at his drink, and he suddenly fell to earth with an awful convulsion.... he spoke no word afterwards... and he passed away on the 8th June." He was succeeded by King Edward the Confessor.

|

|

1044

|

King Edward the Confessor now handed all of former Queen Emma's West Suffolk income over to the monastery at Bury under Abbot Leofstan, who was only the second Benedictine abbot there. In modern English it includes the following clauses:

"Edward the King greets Bishop Grymketal and Aelfwine, and Aelfric and all my thanes in Suffolk friend-like; and I make known to you that I wish that land at Mildenhall and the nine less a half hundreds in sanctuary to Thinghoo belong unto St Edmund with soke and sack as full and as forth as it stood in my mother's hand...."

|

|

1066

|

King Edward the Confessor died on 5th January 1066, and the Chronicles say that he committed the kingdom to Harold Godwinson. Within a year the Normans had invaded England. On 25th December 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned King of England and Anglo-Saxon England was no more. The Norman Conquest had taken place, and would be followed by a great takeover of Saxon property.

|

|

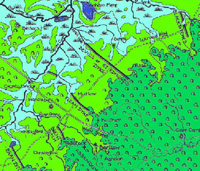

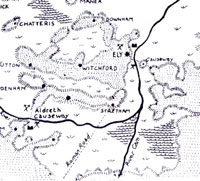

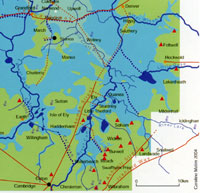

The Fens in 1071

The Fens in 1071 |

|

1071

|

The revolt of Hereward the Wake in 1070 and 1071 has been said to be a minor affair by contrast to the northern revolts, but has attracted more attention from some writers. Trevor Bevis thinks that of all the revolts, "that occurring in the fens was the most serious." Peter Rex calls Hereward "the last Englishman."

Following his raid on Peterborough in 1070, Hereward was a hunted man. He believed that he could seek refuge on the Isle of Ely, and that he would be accepted by the monks there.

At this time the water table in the Fens was probably 30 feet higher than it is today, with swamp and marshy, reedy waterways the norm. There was no agriculture of the type seen today. Instead it was a vast fishery, with some reed cutting where possible, and grazing in the summer months. Eels were widely trapped, even giving Ely its name. Ely was an island with four main landing places or hythes. Even at Bury the River Lark was deeper than it is now, with the town almost surrounded by the waters of the Lark, Linnet and Tay Fen, and their flood meadows. The River Lark then joined the Ely Ouse at Prickwillow.

The Isle of Ely itself was a haven by comparison to the surrounding Fen. The isle covered seven miles by four miles and enjoyed a high standard of farming on its drier rich soil. The Abbey itself was a rich endowment, and the town of Ely was substantial.

The revolt was soon crushed, and the losing Saxons had more of their lands confiscated.

Of the 10,000 men who crossed the Channel with King William, some 2,000 were rewarded with grants of land. Within a short time, ten of King William's relatives owned 30 per cent of English land. Prominent among them in Norfolk were the Bigod and Warenne families. The Bigods also had great estates in Suffolk.

|

|

Click for more on Domesday

|

|

1086

|

At St Edmund's Bury the Domesday book recorded 500 dwellings, and many of the inhabitants depended on the monastery for a living. Some 75 bakers, ale brewers, tailors, washerwomen, shoe and robe makers, cooks, porter and purveyors "daily wait upon the Saint, the Abbot, and the Brethren." The Domesday Book recorded 30 priests, deacons and clergymen in Bury together with 28 nuns and poor people who "daily utter prayers for the King and all Christian people". Bury's population might have grown to 2,250 by 1086. The town was now valued at £20, or twice its value in 1066.

|

|

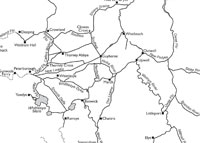

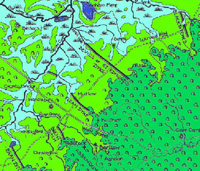

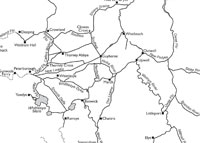

Fenland waterways 1604 redrawn by M Chisholm

|

|

1090

|

By 1090 work had begun on the great new church for the abbey of St Edmund. Most of the stone was to come by river boat from Barnack quarries near Peterborough.

In his Opera Posthuma of 1745, "Antiquitates S Edmundi Burgi", John Battely, the late Archdeacon of Canterbury, discussed the shipment of stone from Barnack, and referred to a an order to Peterborough, issued by William the Conqueror, that Abbot Baldwin of Bury, be permitted to have as much stone as needed for the monastic church 'as he has had up till now and not to make any further hindrance for him in bringing stone to the water which you have formerly done.' Batteley refers to Gunwade as being the location where the stone was loaded on to boats on the River Nene. Professor M Chisholm argues that it would have been cheaper to load stone at Pilsgate on the River Welland and take the 9 mile longer river route, via the Crowland Cut, but obviating the shorter, but much more expensive 4 mile land route to Gunwade.

Barnack,Gunwade and Pilsgate are all visible on the attached map by M Chisholm, published in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, 2010 and 2011. Click on the thumbnail for a larger version. Chisholm suggests that both routes may have been used at different times.

|

|

1105

|

The rivalries between the abbots of the great monasteries could result in interference with their river trade. Bury abbey needed to bring stone from the Barnack Quarries to build the great new abbey church. Peterborough monks had apparently seized the barges bringing stone to Bury St Edmunds in order to levy a toll. Henry I had to issue a writ to stop this practice.

Writ of 1105, quoted by M Chisholm, Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, 2011:-

"Precept by Henry I to William de Cahaines the sheriff (of Northants) and the monks of Peterborough: That no toll is to be taken from the stone which is being conveyed to make the church of St Edmund. They are to restore without delay the ships which they have seized." (Johnson and Cronne 1956, item 694, 42.)

|

|

Bury by 1150

Bury by 1150 |

|

1150

|

By this time,

according to the Gesta Sacristarum, Harvey the Sacrist also built the town walls of Bury to replace the ditch from the West Gate to the North Gate.

Chequer Square was at this time called Paddock Pool and its swampy nature was a problem for the medieval builders.

|

|

Battle of Fornham

|

|

1173

|

Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, now raised a force of French and Flemish mercenaries. On September 29th, they landed at Walton near Felixstowe and marched inland.

They joined up with Hugh Bigod, and attacked Haughley castle and badly damaged it, killing many of its defenders.

The Earl of Leicester was persuaded to head for Leicester to capture his home town. So they first headed west, through Suffolk and towards Bury St Edmunds. Beaumont knew that Bury supported the old King, and so he aimed to skirt north of the town.

Meanwhile Hugh Bohun and Richard de Lacey, the army commanders of Henry II in the north had agreed a truce with King William of Scotland, regrouped and were marching south to meet the threat. Local Suffolk people joined them as they neared Bury, in particular those whose homes and families had been ravaged by the Fleming militias.

So in the in autumn of 1173 the opposing armies met at Fornham St Genevieve on the River Lark, some four miles north west of the centre of Bury. The Flemish army was caught as it tried to cross the marshes down to the River Lark looking for a suitable fording spot. Fighting seems to have taken place from the Babwell hamlet, by today's Tollgate Inn, along the valley to Fornham. The rebels' strongest position was somewhere near Fornham St Martin Church.

The Earl of Leicester and his wife, the Countess Petronilla, were captured, but Earl Hugh Bigod escaped to Bungay. The Countess was said to have thrown her ring and other jewels, into the River as a gesture of defiance. The Earl and his Countess were later taken to Normandy as prisoners.

Bones and a few lost weapons have been found in the area of the battle, including the Fornham Sword, which is now in West Stow Museum, on loan from John Macrae, the landowner. This was found when a muddy ditch was being cleaned out near the water mill at Fornham St Martin around 1876.

|

|

1184

|

In about 1184 Samson founded a new hospital called St Saviour's at Babwell. The site is on the Fornham Road, outside the old North Gate. Today it is adjacent to the railway bridge, next to Tesco's store.

St Saviour's backed on to the River Lark, providing water and fish.

|

|

1186

|

Around this time the windmill was introduced to this country. Up to this time all mills were either animal powered or were water mills. A mill built on the Haberden in 1191 must have been one of the first in the country.

|

|

1191

|

Around 1191 Herbert the Dean erected a windmill at the Haberden, off Southgate Street, in Bury St Edmunds. The Guinness Book of Records for 1964 claimed that this was the first recorded Post Mill in England. The post mill was built around a central column or post which allowed the mill to be turned to face into the wind whenever the wind direction changed. If this was the country's first post mill, it did not last very long. To protect his own income from the milling fees, which he charged at his own watermill, the Abbot forced him to take it down. Windmills were the latest technology at this time. Hitherto the watermill had reigned supreme, and it seems that the Abbot had a Water Mill based on the River Lark, within the Abbey precincts. Water power itself had replaced the animal power long used in earlier times to grind corn.

|

|

1200

|

Through the 1190's and early 1200's, the new technology of the time in the wool trade was the invention of the water driven Fulling Machine. This was to turn England from being an exporter of raw wool to Flanders and the Low Countries, into a manufacturer of textiles on an industrial scale. This needed fast flowing water to drive the machines and new centres would grow up in the Cotswolds, and also in and around the Stour Valley, not far from Bury, over the next hundred years.

|

|

1215

|

After denouncing his own Magna Carta, John had to pacify the Barons who had forced it upon him. As part of this campaign

King John relieved his loyal town of Lincoln in September and marched on Kings Lynn. While crossing the Wellstream which flowed into the Wash, his baggage train got lost in the mists and swallowed by quicksand. His royal jewels and treasures were lost.

|

|

1257

|

During July there was heavy rains and extensive areas were flooded. Much of the corn harvest was destroyed or badly damaged.

|

|

1265

|

By 1265 the Abbey finally gave the Franciscans land for a permanent home at Babwell just outside the Banleuca where today's Priory Hotel stands. With land given reluctantly by the Abbey at Bury, and financial help from the Earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare, the Franciscan Friars finally founded their Friary at Babwell. The name Babwell no longer survives, but the Priory Hotel stands within the walls of the old Friary precincts at the junction of Tollgate Lane and the Mildenhall Road. Only remnants of the walls remain visible today.

The Friary backed on to the River Lark, and the Friars would soon establish their own watermill. There have been remains of a mill found behind the Tollgate Inn, possibly associated with the Friary.

|

|

1273

|

In March there was so much rain that there were floods worse than any since 1258. Water rose 5 feet above the bridge at Cambridge, and the damage at Norwich was said to be worse than the ravages of either the disinherited or the king's men last year.

|

|

1277

|

A cloudburst in October caused many men and livestock to be drowned in the floods. The storms were worst in Essex and Cambridgeshire and around Bury itself.

|

|

1281

|

In 1281, the manor of Haberdon, or Haberden, was granted to the Sacrist of the abbey by Henry, son of Nicholas of St Edmund. This would add to the sacrist's income, and included a mill, and at least 51 acres. As the abbey gained more and more of the local pasture land, any common rights hitherto exercised by local people were gradually extinguished by the new owner.

|

|

1282

|

A record in William of Hoo's Letterbook concerns a lease of a toft, or shop, in Icklingham, together with a Fulling Mill. This would have been located on the River Lark, using a combination of water and Fuller's Earth to clean the grease from woollen fleeces. William the Sacrist would receive his annual rent from the lessees, Robert the Fuller of Icklingham and his wife Cecily.

|

|

1290

|

The cellarer had dammed up the Tayfen brook, and flooded some lands used by towns people. The leading townsmen were united against this act, and called a meeting in the Guild Hall. They then set out to destroy the dam. In October, a commission was set up to enquire into their actions, but this only made matters worse. This rumbled on into more violence in 1292.

|

|

1300

|

During the 14th Century, from 1300 to 1400 Bury St Edmunds had a flourishing fishing industry. Amazingly to us today, the Rivers Linnet and Lark, with the waters at Tay Fen and Babwell Fen, supported large fish populations. These provided employment for fishermen and food for the town and abbey, as well as a means of transport, source of drinking water and a means of waste disposal. Gradually the pressure of the fulling mills and their waste products, and a rise in population pressure would cause a decline in fish production.

In the century 1300 to 1400 it seems that the climate was much warmer than today. On a global scale the glaciers were melting, resulting in a rise of sea level, to about half a metre higher than it was by about 1987. Coastal erosion accelerated at an alarming rate, destroying some coastal communities, and severely damaging others. In Suffolk, the prosperous port of Dunwich would become the best known casualty, but on the Humber, the port of Ravenspur would suffer the same fate. It is likely that inland the river levels would also tend to rise, as sea level rose.

|

|

1306

|

The gaol in Bury at this time was fairly dilapidated and in this year William Pugg, imprisoned on a charge of trespass on the abbey's fishponds, broke out.

|

|

1342

|

The rise in sea levels since about 1300 had severely affected the coastal communities by this time. In particular, by 1342, Dunwich had lost 400 houses, together with the churches of St Leonard's and St Martin's. A century earlier it had been at the height of its power and prosperity as one of the largest ports in eastern England, perhaps about half the size of London.

|

|

1379

|

Although Bury and Thetford were inland towns, they both acted as ports, particularly Thetford as it had a bigger river. In 1379 the royal council ordered the two towns to build a ship to be incorporated into the royal navy. This was a feudal duty of the town bailiffs in Bury.

|

|

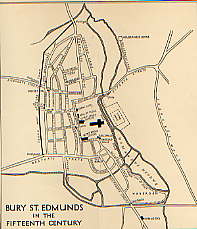

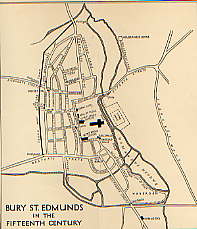

Lobel's map of Bury |

|

1433

|

This map of Bury by M D Lobel shows the River Lark, the Linnet and the Tayfen Brook enclosing the medieval town.

|

|

1440

|

From about 1440, the rearing of sheep became more profitable around Bury than the rearing of cattle. Cattle had been kept for years in and around the town, supporting the leather industry as well as for food. The wool from sheep was now becoming much more valuable for weaving into cloth. This led to an extension to the number of sheep folds around the area.

With the increased cloth production around Bury, it would appear that the fulling and dying of cloth were polluting the waterways of the town. At any rate the number of people in the town calling themselves fishers seems to have fallen dramatically at this time. The river and fen fishing industry became moribund.

|

|

The Banleuca by 1450

|

|

1450

|

From 1450 to 1530 the cloth industry would reach a peak of prosperity.

This was particularly marked in the broad cloth area of Suffolk, between Clare, Bury St Edmunds and East Bergholt. Bury St Edmunds was the principal market outlet for the woollen cloth of the Stour Valley, as well as being a major producer in its own right. Merchants came to Bury's wool markets from London, Norwich, Kings Lynn, Great Yarmouth, the Low Countries, Germany and Italy. They were seeking the cloth from the finest fleeces in Western Europe.

As well as the better known textile villages, places within ten miles of Bury like Woolpit, Rattlesden, Thorpe Morieux, Boxstead, Icklingham, Stanstead and Mildenhall were centres of the weaving trade, sending cloth to Bury. Today, Lavenham and Long Melford are well remembered as wool towns, but it is important to understand how widespread the trade was in this area.

Some clothiers would become extremely rich on this trade, particularly in Babergh and Cosford hundreds. Lavenham became the greatest centre for cloth with the most clothiers. Hadleigh, Lavenham and Bury St Edmunds had the greatest output of cloth followed by Ipswich, Nayland, Waldingfield, Long Melford and Sudbury.

By 1450 it is reckoned that about half of Bury's export trade was through Kings Lynn, by way of the Rivers Lark and then along the Great Ouse.

|

|

1455

|

By the mid 1400's the Breckland area to the north-west of Bury, began to change in character. The light soils had been ideal farmland from the earliest years because of its good drainage and easy ploughing and cultivating. By this time the soil was exhausted, and tillage gave way to the keeping of sheep and rabbits. Climate change may also have resulted in lower rainfall resulting in crop failures. Sheep farming was also becoming more profitable, but the resulting over grazing would lead to the great erosion problems of later centuries.

|

|

Moulton Packhorse bridge

|

|

1477

|

Moulton, a village four miles east of Newmarket, is known for its 15th century Pack Horse Bridge, now maintained by English Heritage. The bridge is on the old Cambridge to Bury St Edmunds packhorse route and was one of the main arteries for Bury's wool trade. Its low parapet walls enabled the packs to swing clear and avoided the need for a wider, more expensive structure. However, it was probably not restricted to packhorses, as it is wide enough to allow the passage of small carts. It can still be used to cross the River Kennett, but nowadays the river is usually completely dried up. There was probably another packhorse route from Clare to Newmarket joining up with this route.

The River Kennett drains towards the north west, flowing into the Lee Brook at Freckenham, and thence into the River Lark between Jude's Ferry and Isleham.

|

|

1531

|

Henry VIII agreed his Bill of Sewers, and appointed a Commission to maintain sewers. In those days a sewer was not meant to take solids. A sewer was understood to be a watercourse, pipe or tunnel to take rainwater from streets and house roofs to prevent flooding and undermining of property, and from fields to drain crops. Disposal of solid waste was considered a private matter, and the privy usually discharged to a midden in most towns.

|

|

1534

|

In about 1530 John Leland, the Keeper of the King's Libraries, toured around East Anglia. As the king's Antiquary, he was looking for ancient books and records. The dates are unclear as he made various trips round England over a ten year period. It is said that in 1534 John Leland visited Bury. Most of his comments on provincial towns were far from flattering, but in the case of Bury he wrote that:

"Why need I in this place extol Bury at greater length? This only will I add, that the sun does not shine on a town more prettily situated, so delicately does it hang on a gentle slope, with a little stream flowing on its east side, nor on an abbey more famous....

The streamlet, which I just now mentioned, flows through the midst of the abbey precinct, gaining access thereto by a double bridge vaulted over it."

The "little stream" does not seem to have been named the Lark until about the seventeenth century. In 1699 there was enacted "an Act for making the River Larke, alias Burn, Navigable". In 1534 it was small and shallow and could not take deep draught vessels, so only flat bottomed barges could reach the town, usually poled by men or pulled by oxen or mules.

|

|

1536

|

The Dissolution of the Monasteries really began when the Act of Suppression authorised the closure of monasteries with an annual income of less than 300 marks (about £200). This Act began to be enforced in 1536. It covered 300 houses but about 75 were exempted upon payment of a fine.

In Bury this order did not cover the great Benedictine Abbey, but it did cause the Babwell Friary of the Franciscan Order to be shut down. Its site on the Lark, together with its watermill, became Crown property. The property of the Babwell Friary was then sold to Anthony Harveye, a gentleman.

|

|

1539

|

In September 1538 the Kings Commissioners had arrived in Bury to confiscate its wealth. The property of the Abbey of St Edmund was not formally surrendered to the Crown until 4th November 1539 but much of the wealth had already been confiscated in the previous year.

|

|

1542

|

There were a series of droughts in the 1540's, and the resulting food shortages pushed prices up further. In 1542 the Thames dried up to a trickle, followed by widespread crop failures and many small farmers were forced out of business.

|

|

1550

|

The climate has not always been just as we experience it today. We all know about the Ice Age which was thousands of years in the past, but from about 1550 to around 1850 there was a cooler period, sometimes called the Little Ice Age. Prior to this time there had been a warmer period, called the Medieval Warm Period, from about 800 to about 1300.

After the mid 1500's there were colder winters than we are used to today, with great hardship for man and beast.

|

|

1560

|

On 14th February, 1560, Queen Elizabeth in consideration of £412 19s 4d. paid by John Eyer, Esq., granted him (amongst other things) "All that the site, circuit and precinct of the late dissolved Monastery of Bury, otherwise called "Bury St Edmunds" amongst the specified lands and buildings being the Dorter Court, the Garners, the Abbot's Stables, the Gate House, the Great Court, the Pallaies Garden, the Lecture Yard, Bradfield Hall, the Pond Yard and the Vine."

The abbey's fishponds were therefore still visible at this time, but it is unclear if they still held fish.

|

|

River Lark 1575 by Christopher Saxton

|

|

1575

|

A map of Suffolk by Christopher Saxton, was published in 1575. Although the River Lark and the Kennet and Lee Brook were drawn on this map, they were not given any names. The Great Ouse is labelled 'Owse flu', while the Little Ouse at Brandon is labelled 'Owse parva flu'. Flu is short for fluvius or river, in Latin.

|

|

1586

|

The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland were published in 1577. Raphael Holinshed worked for the London printer, Reginald Wolfe, as a translator, and was asked by Wolfe to produce a History of the World for him to print and sell. Wolfe died in 1573 and three booksellers took over the project, and took on Holinshed together with other writers, to complete it. Only the British parts of this project were produced, and were sold as Ralph Hollingshed's Chronicles. Holinshed himself died in about 1580.

A much revised and improved edition of the Chronicle was produced by 1586, went on sale from 1587, and this version became immensely popular. William Shakespeare used Holinshed as a source for some of his plays. It became used as an almanac and travel guide as much as a history. In this Chronicle the river at Bury St Edmunds is referred to as the Burne.

|

1600

|

To follow the story of the River Lark navigation

after 1600, please click here.

|

|

Books consulted:

The Lark Navigation by D E Weston, 1980

Background to Breckland by H J Mason and A McClelland, 1994

The Lark Valley by the Lark Valley Association, c1999

An Historical Atlas of Suffolk: Suffolk County Council, David Dymond and Edward Martin, 3rd Edition, 1999

|