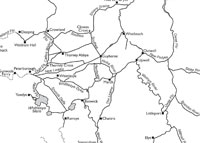

River Lark 1575 by Christopher Saxton

|

The River Lark

After the year 1600

Pre

1600

|

Please click here to look back at the River Lark before 1600

|

|

1600

|

In 1600 it was still possible for sailing boats to reach Mildenhall on occasion, from the sea. The tidal nature of the Great Ouse penetrated deep inland. Sea fish had been occasionally caught as far upriver as Cambridge. However, it was also generally agreed that the Fens were drowning under constant inundations.

In 1600, an Act of Parliament was passed for the recovery of many hundred thousand acres of marshes. Adventurers, as they were known, could venture to carry out drainage projects at their own cost, in return for which they could keep large acreages of the land so recovered. No major work took place for some decades.

|

|

1603

|

Around the period 1600 to 1605, the Chorography of Suffolk was written by an unknown author. He described the rivers of Suffolk, but he had no name for our River Lark. His source for this seems to have been Saxton's Map of Suffolk, dated 1575, with a dash of his own ideas thrown in. Saxton's spellings were perpetuated and further bungled by the chorographer. On the Lark he wrote as follows:

"Not farre from Burne Bradfeld above the greater Feltham springs another litle river that runneth to Nawton, Burye, Fernhams, Hengrave, Flempton, Lackforde, Icklingha', Berton & Mildenhall & between Islam in Cambridgeshire & Worlington in Suff. it meeteth with another litle river that springeth about Catlidge (called the Dale water) in Cambridgeshire & Lidgate in Suff. which from that in a continuall streame dischargeth itself into the Greater Ouse betwene Ely and Littleporte in Cambridgeshire."

This note was adjacent to a paragraph heading of "Burne fl", presumably short for Burne fluvius or River Burne. This erroneous jotting may be the derivation of the name Burne used for the Lark in the Act of parliament to be passed in 1699/1700.

We might translate this passage as follows:

"Not far from Bradfield Combust, uphill from Great Welnetham, springs another little river, (today called the River Lark), that runs through Nowton, Bury, the Fornhams, Hengrave, Flempton, Lackford, Icklingham, Barton Mills and through Mildenhall. Between Worlington and Isleham it is joined by another little river that rises between Kirtling and Lidgate, (today called the River Kennett, and, from Freckenham, the Lee Brook.) Together these discharge into the River Great Ouse between Ely and Littleport."

|

|

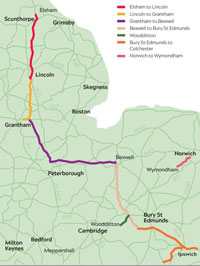

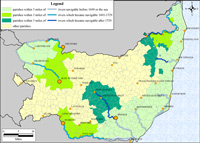

Fenland waterways 1604 redrawn by M Chisholm

|

|

1604

|

In 1604 William Hayward published a map of the main elements of the river systems in the Fens at a scale of one inch to the mile. His original map has been lost and we are reliant upon later copies, particularly that of Payler Smith, drawn in 1727.

Professor Michael Chisholm has re-drawn and adjusted this map and published it in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society in 2010, with further considerations in PCAS 2011. Clicking on the thumbnail will reveal the full map.

The pecked lines show rivers which extended outside the scope of Hayward's map. Hayward's names are retained.

Chisholm suggested that Crowland, and its triple arched Trinity Bridge, was a key factor in the medieval navigational network. Chisholm called a key waterway here the Crowland Cut, an artificial canal which Hayward called Nene flu., linking the Nene and Welland.

|

|

1618

|

By 1618 Robert Reyce had finished his Breviary of Suffolk. This was published in 1902 as Suffolk in the 17th Century, by Lord Francis Hervey. Unlike the Chorography, it did not attempt to list every town, village and hamlet in Suffolk. Instead it discussed a series of topics, such as rivers, the soil, the agricultural products, mansions, the classes of people, lords of the manor, former religious houses, monuments in churches, coats of arms, etc..

The River Larke is again called The Burne, while the Kennet is called the The Dale.

"This Burne ariseth nott far from Burne Bradfeild......."

In his notes added to the 1902 publication, Lord Francis Hervey noted that: "The 'river of Dale' is now known as Lee Brook. 'Burne Bradfeild' is Bradfield Combust. The name has nothing to do with the name of the River Burn or Larke."

|

|

1621

|

The River Lark was at this time a mixture of gravelly shallows and easy fords, with reasonable depths of water in other places. Small boats and vessels could reach as far as Mildenhall from the sea at Kings Lynn, but it was too difficult to reach any further with the same boat.

If the river could be modified, or deepened in some way, then more goods could reach Bury St Edmunds without needing to leave the water. The use of single gates or staunches to hold back water in a section of river, had been known for hundreds of years.

The first known attempt to seriously improve the River Lark for navigation since Roman times took place in 1621. Plans were prepared by a John Gason of Finchley, and authorisation was sought by way of an Act of Parliament. Gason also tried to be appointed the undertaker for several other rivers, including the Lark, but this bill was rejected by Parliament.

|

|

1630

|

The first major attempt at drainage in the fens occurred when the Earl of Bedford agreed to drain an area which became called the Bedford Level. In 1634 Sir Cornelius Vermuyden was employed by a company headed by Francis, Earl of Bedford to drain a large area of land now known as the Bedford Level. The work included the (Old) Bedford River and nine other major drains. By 1637 this work was completed.

|

|

1635

|

The attractive profits to be made by reducing the cost of transporting goods across country continued to make river improvement an attractive idea. In 1635 the entrepreneur Henry Lambe managed to obtain an Order in Council which gave him permission to carry out whatever work was needed to make the river navigable from Mildenhall to Bury St Edmunds.

However, all along the river there were watermills which depended upon a free flow of water for their existence. In some cases they were situated on mill streams flowing into the river, but in some cases they sat upon the river itself. Although these could all be avoided by digging new cuts around the mills, some millers feared the worst.

After proceeding only one mile, the landowners Sir Roger North and Thomas Steward, lodged objections, as a miller claimed that the contractors had damaged his mill. They managed to get the work stopped.

|

|

1636

|

Apparently Lambe managed to get permission to restart the works, but only if he paid treble the cost of any damage to mills, and agreed to pay an exorbitant price to buy any necessary land for towpaths and cuts.

|

|

1637

|

Following a direct appeal to King Charles I, the King summoned all parties to explain why they were holding up this important work. He granted Henry Lambe a license to proceed, for an annual fee of £6.13.4. In return Lambe could charge a toll along the river from Bury to Mildenhall.

Unfortunately no further record of these improvements appears to be known about at present, and it may well be that the Civil War finished Lambe's hopes of proceeding.

It would be another 60 years before the Lark got its navigation work started again.

|

|

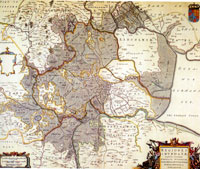

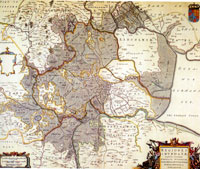

The Fens 1648 |

|

1648

|

In 1648 J Blaeu produced his map of the Fens entitled "Regiones Inundatae in finibus comitatus", or the areas of the fens subject to flooding. He placed north to the right of his map. This map shows the Fens and its rivers as they were prior to the great drainage works by Vermuyden and others.

|

|

1649

|

In 1649 a second Drainage Act had been passed to promote further work in Fenland drainage. Once again Cornelius Vermuyden was in charge of the work. This work would include the building of a sluice at Denver, with far reaching consequences for the Great Ouse and its tributaries, including the Lark.

|

|

1651

|

Up until 1651 the River Lark had been directly connected to the sea, and was tidal as far up as Isleham. Smaller sea going vessels had unimpeded access to the hinterland, and were able to penetrate as far as there was draught below their keels. After this time the new drainage works would move the tidal influence to below Denver, and sea going vessels could pass no further.

|

|

1652

|

From 1634 to 1637 Sir Cornelius Vermuyden was employed by a company headed by Francis, Earl of Bedford to drain a large area of land now known as the Bedford Level. The work included the (Old) Bedford River and nine other major drains.

In 1652 Sir Cornelius Vermuyden completed drainage works on the Great Ouse that he had worked on since 1649. This included the cutting of the New Bedford or Hundred Foot river parallel to the Old Bedford River.

The Denver Sluice was constructed at the head of the River Great Ouse. This construction isolated the Great Ouse and its tributaries from the tidal effects of the sea, and is thought to have contributed to the silting up of the Little Ouse and the River Lark. This, in turn, would lead to the need to improve the waterways for navigation after the needs of drainage had been catered for. In 1670 it would become necessary to improve navigation on the Great Ouse and the Little Ouse, or Brandon River, as it was also called.

After 1652 it was often the case that the Denver Sluice was closed for weeks on end. This meant that all ships heading upstream had to halt at the sluice and portage the cargo around it. This led to the development of the Fenland Lighter, an unpowered barge which suited the shallower and sheltered waters of the inland waterways. A fenland lighter was 42 feet long, 10 or 11 feet wide and could carry about 25 tons. They were usually strung together in "gangs" of 5 vessels, drawn by a lone horse from the river bank.

|

|

1668

|

The Breckland area to the north-west of Bury, was suffering from constant erosion of the sandy soils by the wind. The great open treeless plains were by now well over-grazed by sheep and rabbits. This culminated in a great sandstorm in 1668, when masses of sand were blown from Lakenheath to Santon Downham, blocking the River Little Ouse, and partly burying the village.

Other Breckland rivers may have also been affected by erosion and wind blown silt.

|

|

1670

|

Drainage works in the Fens had contributed to the silting up of the river systems inland. In 1670 Acts of Parliament were obtained for the the Improvement of the navigation on the Great Ouse and the Brandon River, or Little Ouse. An attempt to do the same for the River Lark was made in 1682.

|

|

1674

|

A man called Henry Ashley leased the navigation rights on the Great Ouse and built sluices all the way up to Bedford, proving that he could make a river navigable up to 74 miles from the sea. In 1680 his son, also called Henry Ashley, bought himself a share in that river as well.

|

|

1682

|

The River Lark was by now silted up and unsuitable for navigation by barge. In 1682 an Act of Parliament was sought to improve it, according to Mason and McClelland. However, it is thought that this probably refers erroneously to the Act of 1699/1700.

|

|

1693

|

Henry Ashley, the proprietor of the Great Ouse Navigation, was turning his attention to the River Lark. The Lark had become silted up and was no longer suitable for barge traffic. Ashley had plans to canalise the Lark and to be able to run barges up to Bury St Edmunds, thus restoring the ancient trade links to Kings Lynn. He was already having discussions with landowners along the river. In March, 1693, he made an agreement with William Gage of Hengrave Estate to allow him an exemption from all canal tolls on the River Lark for coals, fuel, corn, fodder and materials for building or reparation work to be used in or about Hengrave Hall. His River Lark Navigation Bill was already pending in Parliament.

|

|

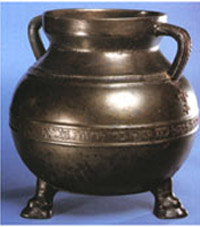

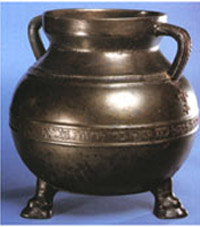

Bodleian Bowl

Bodleian Bowl |

|

1696

|

In 1696 a bronze alms vessel of Jewish origin, with a hebrew inscription, was recovered from the River Lark at Bury. It was 5 kilos in weight and had a nine litre capacity. It has been suggested by Robert Butterworth that this may have been discarded following the looting and extreme violence against the Jews in Bury in 1190.

|

|

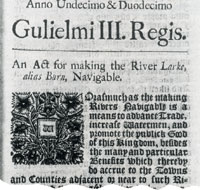

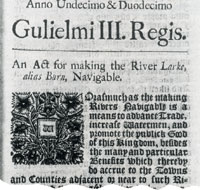

Lark Navigation Act

|

|

1699

|

In the 11th and 12th year of William III's reign was enacted "An Act for making the River Larke, alias Burn, Navigable." This Act has been dated in modern times as either 1699 or 1700. The general preamble stated that "the making of rivers navigable is a means to advance trade, increase Watermen, and promote the public good of this kingdom, besides the many and particular benefits which thereby do accrue to the towns and counties adjacent or near to such rivers."

Henry Ashley, his heirs and successors, were empowered to make the River Lark navigable from Long Common, which was just below Mildenhall Mill, to Eastgate Bridge in Bury St Edmunds. At this time the river was still navigable from Kings Lynn up to Long Common in Mildenhall.

The Act included various provisions to assist the work, but included some restrictions, as follows: - Commissioners were appointed by the Act to oversee its provisions, and 39 gentlemen of the area were named as Commissioners, along with the Alderman, Coroner, Recorder and the six Assistant Justices of the Peace of Bury St Edmunds. The qualification for becoming a Commissioner was that the individual had to be receiving at least £300 a year from land, or be worth £6,000 overall.

- No public or common wharf was to be set up within the Borough of Bury St Edmunds without the consent of the Corporation and at least 7 other of the appointed Commissioners.

- William Gage of Hengrave was to continue to have free use of the river for transporting hay and manure between his farms.

- In addition, a ditch had to be dug to separate his lands from the towpath.

- Gentlemen or persons of quality would be allowed to keep a pleasure boat upon the river without payment of any toll.

The full text of this Act is available from the River Lark homepage or by clicking here: River Lark Act of 1699 (Use your browser's 'back' button to return here.)

|

|

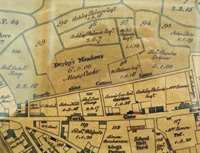

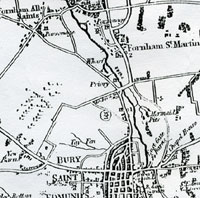

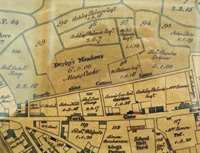

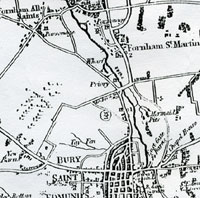

Ashley Palmer - Warren's map of 1791

|

|

blank |

At first the Corporation supported the work. In August 1699 they agreed to help scour the bed of the river at Bury. Ashley explained that his plan was for wharfage to be built from the Northgate towards the Eastgate along the river. In Warren's map of 1791 showing land ownerships within Bury St Edmunds we can see a block of land holdings in the name of Ashley Palmer. By 1791, the Lark Navigation and all its assets had been inherited by Palmer. This block of holdings was undoubtedly originally acquired by Henry Ashley for the purpose of building his wharfage here, with access to both Cotton Lane and Northgate Street.

Local traders objected to these plans, despite the fact that Ashley intended private traders to be able to construct their own wharfs alongside his own. In the end he offered to withdraw from any interest in wharfage at Bury, but for some reason the plans continued to be rejected. His navigation had to be terminated outside the Borough boundary, which crossed the river at the location of Tollgate Bridge. The nearest available land was on the northern side of the Priory Estate, adjacent to today's Somerfield supermarket store.

It took until 1715 for the works to be completed.

The River Lark had clearly acquired its name by this time, but was alternatively known as the Burn, or the Bourne. There is a theory that the River Lark was named after Lackford, as the village name implied that it was a ford for the Lack or Lark in earlier times.

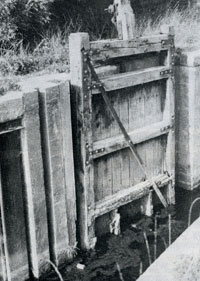

Canal technology at this date did not include the use of "pound locks", as we know them today. Instead they used staunches and sluices. A staunche, or stanche, was like a single lock gate, controlling the level in a stretch of river. Staunches controlled a weir which was made into a slope so that boats could pass from one level to another. Boats either had to navigate with, or against, the rush of water or to wait for the whole of pounds on either side of the weir to become equal. This system is also called a Navigation Weir or Flash Lock. A sluice is a confined water channel that is controlled at its head and foot by gates, and to all intents and purposes appears to have been very similar to a modern lock.

|

|

1700

|

Henry Ashley the younger became the licensed "undertaker" for the River Lark, when the Act of 1699 received its royal assent on 11th April, 1700. He had already worked on building the Great Ouse navigation with his father. Obviously the proposed works were a threat to existing users of the river, in particular, the water millers. One way that Ashley dealt with this issue was to take the problem over to himself. In October of 1700 he leased the Chimney Mills from Lord Cadogan for 25 years. In fact, this mill would remain in the hands of the River Lark Commissioners for the next one hundred years.

|

|

1709

|

Henry Ashley found that he had to make compromises constantly to keep the work going. At Mildenhall he had to rebuild the old cart bridge to allow the passage of his lighters. He agreed with Sir Thomas Hanmer and the Mildenhall parish that he would build it much bigger and better than before, using a brick built span in place of the old wooden structure.

By now Ashley had sold his estate at Eaton Socon in order to finance the improvements on the River Lark.

|

|

1711

|

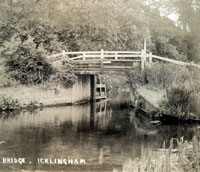

By 1711 Ashley was working at Temple Bridge at Icklingham. Once again he was at the mercy of local landowners. Temple Bridge had existed in various forms for several hundred years, and the maintenance of it was shared between the adjoining estates by long precedent.

Ashley not only paid for the newly raised bridge himself, but had to agree to bear half of the costs of future maintenance.

|

|

1713

|

The Denver Sluice collapsed under the weight of flood waters.

|

|

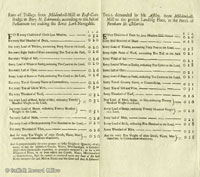

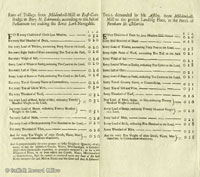

Ashley's tolls for using River Lark

Ashley's tolls for using River Lark

|

|

1716

|

The Lark navigation was now open for business from Mildenhall to Bury St Edmunds under the Act of Parliament passed in 1699/1700. By 1700 the River Lark was no longer navigable any further than Mildenhall from the sea, and so Henry Ashley obtained the Act to allow navigation as far as Eastgate Street. The Corporation of Bury were apparently afraid of him setting up a wharfage monopoly, and opposed the plan. All Ashley could do was build his canal as far as Fornham, outside the Borough boundary.

Ashley's list of charges for moving loads along the new navigation are shown here. As usual, click on the thumbnail to enlarge it. He shows two lists on the page. One is for delivering the goods from Mildenhall Mill to Eastgate Bridge, "according to the Act of Parliament", and is on the left hand side of the page. The list on the right is for deliveries to "the present landing place in the parish of Fornham St Martin." Coal, timber, wool, salt and grain are at the head of the lists, possibly reflecting the expected traffic somewhat. The Fornham Wharf was located adjacent to the Mildenhall Road by making a cut from the river to a point behind the old maltings, adjacent to Somerfield's Supermarket.

It is also interesting to note that quantities are defined by what it was practicable to count during loading. We would weigh coal by the ton and hundredweight before metrication, but here it is measured in "chaldrons", as defined at Kings Lynn; the "Lynn measure". Chambers Cyclopedia of 1728 defined a chaldron as 36 bushels of coal. This would be loaded in bushel baskets of loose coal.

Unfortunately, in 1716 Ashley's fine new brick bridge at Mildenhall was swept away by floods. Now that Ashley had got the river up to standard, he was able to brush aside any suggestions that it was his responsibility to replace the bridge. He wrote to Mildenhall to say that this showed that a bridge with a wooden top would be better than brick, because it would resist such floods much better. Old wooden bridges had survived for decades, proving the point, he wrote.

By 1716 Ashley had acquired the mill at Icklingham, thus removing one possible source of dispute over water rights.

|

|

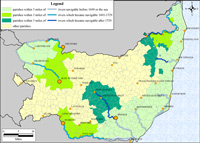

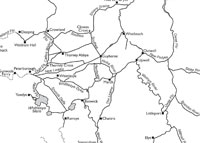

Suffolk navigable rivers

|

|

blank |

This map by Cambridge University shows the impact of improved navigable rivers on adjacent parishes. It shows how many parishes would be within three miles of the navigation once the river Lark (and others) was improved. Lark navigation account books tell us of the many stop-off points that were available along the river to unload cargo. The poorer rural areas were unlikely to unload coal, as it was too expensive, and peat turves were a cheaper alternative. Often public houses would set up and establish small piers to offload deliveries.

The canal seems to have been profitable immediately, largely for bringing in coal to Bury St Edmunds. Between 1716 and 1855 the River Lark would be a busy waterway linking Bury St Edmunds with Ely, Cambridge and Kings Lynn.

In 1716 the Bury coal merchants, Moody and Betts, paid over £55 in tolls for use of the navigation. Boys in the 1960's still called the River Lark behind the Mildenhall Road, "the Coal Rivers". Despite the fact that the river was still in need of further improvements, Ashley took £475.10.4 in tolls on the Lark Navigation in 1716. He stated that he now needed a further £800 to finish the works, but this would result in an even better return.

Although well used, this new navigation had certain inherent weaknesses. - The first was the time needed to negotiate the frequent staunches found on the stretch from Mildenhall to Bury. This made the twelve miles to Bury relatively slow progress.

- Second was the fact that the towpath crossed from one bank to the other because of difficulties with landowners or the state of the topography. The lighters were towed by horses who could not cross the river as easily as men, adding further delays.

- Thirdly, although there was a good demand for coal and goods to be sent upriver to Bury, there was very little trade carried downriver to Lynn.

At first these were not seen as major problems because even slow water transport was far more efficient than the roads at this time. As road transport improved over the next century these shortcomings would gradually become more obvious.

Despite these issues, this phase of the Lark Navigation lasted from 1716 to the railway age of 1855.

|

|

The Priory by 1907

|

|

1722

|

Some local interests continued to plague Ashley. In 1722 there was a dispute with Mr Ralph at Mildenhall Mill. He seems to have had a string of grievances, but he was now threatening to pull up the Mildenhall Lower Staunch. He felt that he was not getting enough water to drive his mill. Ashley had avoided such disputes at Icklingham by buying the mill himself.

Ashley had now apparently accepted that he had to make his permanent terminus at Fornham, just outside the boundary of the Borough of Bury St Edmunds. He bought the Priory Estate from Bridget Short, consisting of 8 acres including Babwell Fen meadows and Bell Meadow.

This purchase included the site of the Franciscan Friary which was dissolved around 1538. Henry Ashley is thought to have built the mansion now known as the Priory, probably incorporating some features of the remaining remnants of the friary buildings.

|

|

1724

|

Daniel Defoe wrote his "Tour through the Eastern Counties" and described Bury at the time as a major social capital. Its old cloth industries had long gone. The weaving of darnex coverlets was declining and only spinning remained as a major manufacture.

Defoe described the river at Bury as follows:

"They have a very small river, or rather a very small branch of a small river....which runs from hence to Milden Hall on the edge of the fens....They have made this river navigable to the said Milden Hall from which there is a navigable dyke which goes into the river Ouse and so to Lynn, so that all their coal, wine, iron, lead and other goods are brought by water from Lynn, or from London by way of Lynn, to the ease of the tradesmen."

|

|

Abbot's palace in 1725

|

|

1725

|

This picture of the ruins of the Abbot's palace in the grounds of the Abbey of St Edmund was taken from a watercolour painted in 1725. It was engraved for printing by R Godfrey in 1779. If you click on the thumbnail to see the full picture, it shows the dovecote on the extreme left which can still be seen today. It also shows one arm of the River Linnet flowing immediately in front of the dovecote. At this time the Lark and the Linnet ran parallel to each other until they joined at the Abbot's Bridge.

|

|

1727

|

One of the improvements which Ashley carried out after opening the Navigation was the Mildenhall Sluice. In 1727 his local manager informed him that the Mildenhall Sluice was entirely finished.

|

|

1730

|

Henry Ashley junr was born in 1654, the son of Henry Ashley, (1630-1700), a tanner from Huntingdon who had leased the navigation of the River Great Ouse. Henry junior had taken over from his father, and made improvements to the Ouse, and in 1699 had been the promoter of the Act to provide the Lark Navigation.

In 1730 Henry Ashley died, and in his will he divided his estate between his two daughters.

Part passed to his daughter Joanna, who was married to a Joshua Palmer, and part to another daughter married to a Mr Burch. Unfortunately they could not agree who got which assets, and from 1730 until 1742 there was a protracted legal dispute over the rights to the River Lark as well as other property. Not until 1742 was judgement concluded which gave the Lark to the Palmers. The Lark navigation would continue within the Palmer family for the rest of the century.

|

|

1735

|

In August 1735 John Kirby published his book called "The Suffolk Traveller". Of Bury, Kirby wrote in glowing terms, and also noted that:

"Bury St Edmunds is situate on the west side of the River Lark, which is at present navigable from Lynn to Fornham, a mile north of the town."

Goods were not just delivered to Bury St Edmunds, but were dropped off at villages along the river as required. The miller at Icklingham was being paid 40/- a year in 1735 to look after the Temple Staunch, and £5 a year for collecting the tolls payable on deliveries to Icklingham.

|

|

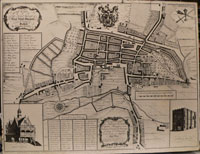

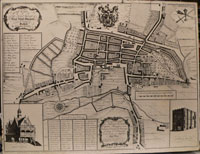

Downing's Map of Bury

|

|

| |

1741

|

In 1741 Alexander Downing published his map of Bury, which looks very curious to modern eyes, with west at the top of the plan. The rivers Linnet and Lark were shown as still flowing in parallel through the Abbey precincts, to join just before the Abbot's Bridge.

|

|

1742

|

From Henry Ashley's death in 1730 until 1742 there was a protracted legal dispute over the inherited rights to the River Lark and his other property. Not until 1742 was judgement concluded which gave the Lark to his daughter Joanna, who was married to Joshua Palmer. The Lark navigation would continue within the Palmer family for the rest of the century.

Along with the navigation the Palmer family now took over the Priory, a mansion on the Babwell Friary site.

|

|

1757

|

The Lark navigation and its associated lands and properties was inherited by Ashley Palmer, the son of Joshua and Joanna Palmer, nee Joanna Ashley.

|

|

1768

|

By the 1760's all the wool used in the Suffolk yarn industry came from long fleeced wool brought from Lincolnshire and some other counties. This wool was traded in two wool halls in Bury, having been brought in from Stourbridge Fair and from London markets. Stourbridge was the source of most of the wool sold into Norfolk and Suffolk. Defoe had called it the biggest fair in the nation.

The short fleece wool from Suffolk and Norfolk sheep was sold in these woolhalls and then had to be sent to Yorkshire to be carded and spun for woollen cloths. Our local sheep were bred more for eating, and had not produced long staple wool since the seventeenth century.

Lincolnshire wool arrived in Bury via the waggon service to Stamford, and from the Midlands by way of the Lark navigation to Kings Lynn and beyond. Ships also landed wool at Ipswich, and at Yarmouth, which could be waggoned to Bury.

The best of the Romney Marsh wool, from Kent, also went to Norwich and to Bury.

The combs used in the combing of wool needed to be heated, and James Oakes seems to have been bringing in coal for this purpose via the Lark Navigation, by this time. This also probably led him to sell coal on to other local users, as by 1788, he was included in a list of Bury coal merchants.

|

|

1775

|

Ashley Palmer, the proprietor of the Lark Navigation, married Susanna Cullum, one of the Cullums of the Hardwick and Hawstead estates, just south of Bury St Edmunds.

|

|

Part of Warren's map 1776

|

|

1776

|

Thomas Warren junior updated and re-issued his father's map of Bury, produced first in 1748. The Rivers Lark and Linnet are still shown as flowing in parallel through the Abbey precincts, only joining up just before the Abbot's Bridge.

|

|

1780

|

Toll records survive for the period from 1780 to 1810 which allow the various cargoes to be assessed. Coal continued to be the main cargoe, but a long list of other goods includes wine, stone, bricks, deals, cheese, barley and wool.

|

|

1785

|

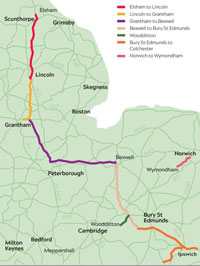

To illustrate the enthusiasm for canals at this time, a Mr John Philips published a plan to build a canal from London to Norwich. It would enter Suffolk at Sturmer, and pass through Wixoe, Melford, Lavenham and then north to Eye and Attleborough. The canal would proceed on to Norwich, with a branch off to Kings Lynn.

This canal never attracted support, but the published plan is available in the West Suffolk Record Office.

|

|

1788

|

By this time, James Oakes was also a dealer in coal, bringing in his stocks on the Lark Navigation.

|

|

1789

|

Parts of the River Lark were now too shallow for comfortable navigation. In 1789 Ashley Palmer began to build a new staunch at Bailey's Gravel in Freckenham. This is one of the few constructions for which the date of original building is clearly established.

|

|

1791

|

From 1791 to 1794 was the height of the national mania for investing in canal building. In 1791 a committee was set up in Bury to consider building a 31 mile canal from the Lark at Bury, to the Stour and Orwell estuary at Mistley. During 1790, a suitable route had been laid out by a Scottish surveyor called John Rennie. He showed that the project would need a tunnel of 2,420 yards to go under the hill at Lavenham. The costs involved meant that the idea of a Lark-Orwell Canal died a death.

At the same time the idea of a canal to link Stowmarket to Ipswich was to be developed successfully over the next few years. John Rennie undertook a three day survey in December, 1791. James Oakes and Sir Charles Davers tried to get the Stowmarket canal extended to Bury, but its promoters refused to consider the idea. The Bury men feared that Stowmarket would grow at Bury's expense. They were correct in that Stowmarket enjoyed prosperity and growth in the early nineteenth century because of its success. The 1847 rail link would be the death of this canal as a successful business.

|

|

Part of Warren's map of 1791

|

|

blank |

In 1791 a third edition of Thomas Warren's Map of Bury was produced. This edition showed some of the surrounding countryside, and the Town Fields. The plan also still showed the Lark and Linnet both flowing through the Abbey precincts to join together at the Abbot's Bridge.

|

|

Wharf on Hodskinson's map

|

|

1792

|

Ashley Palmer had owned the Lark Navigation rights since 1757. He died in 1792, and the Lark was inherited by his widow, Susanna Palmer. She had been born Susanna Cullum, and she would manage the River Lark until she became too elderly. In 1792 she was already aged 56 years.

The universal Directory of Britain was published in 1791, covering places in England and Wales. Volume II contains entries for Bury St Edmunds, and refers to events in 1792, and so must have been published no earlier than this year.

One significant entry refers to the use of the River Lark.

Vessels went from Dice's Quay, Sommers's Quay, and Cotton's Wharf. Presumably these were on the Lark Navigation, where it ended behind what is now Somerfield's Supermarket on the Mildenhall Road. The wharf is shown on Hodskinson's map of Suffolk of 1783, and an extract from that map is shown here. The wharf is shown as a cut from the main river to the Mildenhall Road. This cut survived, in a silted up form, until the 1960s. It was filled in with the development of what is now the UPS depot. On the map it is marked north of Bury, just north of the Friary, which is now the Priory Hotel at the foot of Tollgate lane.

|

|

1793

|

Elsewhere in the fens there were further moves to improve drainage. In 1793 the Eau Brink Bill went before Parliament. This would have entailed digging a deep channel on the Great Ouse near Kings Lynn. This might have caused rivers like the Lark to drain more quickly, thus losing water, and hindering navigation. Susanna Palmer objected to the Bill, and managed to stave off the project for twenty years.

|

|

1795

|

In 1795 an Act of Parliament was passed for improving drainage of the Middle and South Levels of the Fens, and for improving the navigation of several rivers. One of these rivers was the River Lark, and a new set of tolls was laid down to pay for improvements. Coal was now to be charged at 2/8 per chauldron, including groundage.

Groundage was the charge made for storing coal at the Wharfside. Mrs Susanna Palmer, the proprietor of the Lark Navigation, had set up a coalyard at the Fornham Wharf, which was divided up into individual plots for the various coal merchants of the town.

|

|

1797

|

Despite the passing of the Improvement Act in 1795, the state of the Lark Navigation was still causing concern among the local coal merchants. The Navigation was owned by the Palmer family, and had been allowed to fall into disrepair. Ashley Palmer had died in 1792, leaving his widow Susanna to manage the waterway on her own. By now she was 61 years old. This decay in the river was hindering the deliveries of bulky goods like coal, which could not economically be brought in by road.

|

|

1799

|

In "The Lark Navigation", D E Weston recorded that in 1799, Mr Dixie Chapman of Mildenhall was building lighters to use on the River Lark. His price for a lighter was 19 guineas.

|

|

1802

|

In November 1802 the poor state of the Lark Navigation, combined with a drought, left the coal yards of Bury St Edmunds empty. There was not enough water to float the barges. Susanna Cullum, the proprietor of the river, was perhaps too old to carry out the necessary improvements.

Records tell us that in 1802, goods were being landed at the villages of Icklingham, Lackford, Flempton, and Chimney Mills, as well as at the Fornham Wharf. Coal was not delivered to most villages as it was too expensive. Coal was landed at Icklingham, probably for the mill, but other villages had turves delivered instead. Nowadays we would call these peat blocks, as peat was a cheaper fuel than coal.

|

|

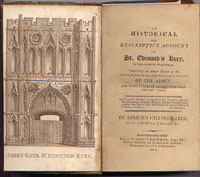

Gillingwater's History

Gillingwater's History

|

|

1804

|

Edmund Gillingwater produced his guide book to the town entitled "History of St Edmund's Bury". He refers to the town's river as the Lark without further comment,perhaps indicating that the name was in general use by this time. The River Lark is referred to by that name, as follows: "the Lark, (whose divided waters are, with others, collected within the abbey grounds into one stream,)..."

|

|

1807

|

Mrs Susanna Palmer, proprietor of the Lark Navigation, was 70 years old in 1806. By 1807 it seems that her nephew, Sir Thomas Gery Cullum of Hardwick House, was managing her affairs on her behalf. These included the River Lark, and part of the Great Ouse, and he was to become an enthusiastic improver of the Navigation. Provisions of the 1795 Act included several for improving the River Lark, and Cullum seems to have felt that it was now up to him to carry them out.

|

|

Fornham coalyards by Warren 1813 |

|

1813

|

Records survive of a survey made by Thomas Warren of the buildings located at the Fornham Wharf at this time. Most of the space was taken up by coal yards in various hands. Plot 1 was occupied by a Mr Lee. Sir Thomas Cullum had a Timber Yard, a Coal Yard and a Carpenters Shop. The carpenter's workshop was for work to be undertaken on repairs to barges and canal stock. There was "An old Salt House," a Granary, Ridley's Coal Warehouse, a Weighing House, and an "old coal yard." The Granary was let to Mr Cooper for £12. 12.0 a year. Ridley's warehouse was let to Thomas Ridley for a 20 year term at 5/- a year. Probably this low rental implies that Ridley had paid for the building to be erected, and in effect this was just a site rent. In addition there were two new cottages for Sir Thomas Cullum's labourers which were not yet occupied. The malt house, which still stands today in a derelict state, was not added until 1851.

|

|

1815

|

In 1815 Sir Thomas Gery Cullum was carrying out improvements to the river at Mildenhall. The Mildenhall sluice was being built at this time, but like many of Cullum's works, it is unclear whether these are rebuilds of older installations, or completely new constructions. Mildenhall Sluice was recorded as 108 feet long. He would continue to repair and rebuild features along the river until his death in 1831. His son, the Reverend Thomas Gery Cullum, then carried on this work into the 1840s and early 1850s. Because both men had the same name, and both were titled by way of the baronetcy, it can be difficult to sort out which man undertook which works. Sir Thomas the elder became 7th baronet in 1785, and died in 1831. The Reverend Thomas became the Reverend Sir Thomas in 1831, and the title became extinct upon his death in 1855.

In 1815 there were floods along the River Lark, and some landowners saw their meadows under water. This was blamed on the River Lark, and so Sir Thomas Cullum sent Mr Bevan to survey the situation. He concluded that in most cases the flooding was no worse than it had been in times past. However, he identified three locations where the river level was normally high enough to prevent meadows draining properly into the river. He proposed that for these three spots it would be possible to build tunnels beneath the bed of the river to carry this water away. Ditches would then take the water away to below the next lock or staunch, where it would drain naturally into the river. Such works can still be seen today at Fornham All Saints, Ducksluice and at West Stow. The 1839 tithe map for Fornham All Saints showed a Tunnel Meadow, which reflected the installation of this culvert, which is still working today. The tunnel at Ducksluice appears to be defunct, and as a consequence, the east bank is often flooded today. At West Stow, the Culford Stream is still carried under the river to join it downstream at Fullers Mill.

|

|

1817

|

In 1817 an Act of Parliament placed the Lark navigation under 80 Commissioners. This Act also consolidated into itself all the provisions of the 1699 River Lark Act, and added several new clauses. At this time the Lark navigation was owned by Mrs Susanna Palmer, but Sir Thomas Gery Cullum, bart., was managing the river on her behalf. The existing Commissioners, who oversaw the proper running of the river, had failed to be kept up to strength, and so it was difficult to get anything changed on the river. New commissioners were put in place by the Act, and Mrs Palmer was also given an increased scale of tolls on the river, which had been unchanged since the 1700 Act. In addition the commissioners were now empowered to carry out works on the river, and pay for them via increases in tolls. The toll set for coals was 4/2 per chauldron.

Both Sir Thomas Gery Cullum, bart, and his son, The Reverend Thomas Gery Cullum, were appointed Commissioners at this time. The Commissioners could now employ a Clerk, paying him up to £40 a year. Meetings had to be held in the Shire Hall in Bury St Edmunds. John Wayman, a Bury solicitor, was the first Clerk to the Commission, and he needed 15 commissioners to attend to make up a quorum.

The 1817 Act also required the owners of the navigation to provide either gates or leaps of the proper height to be made in any fences along the towpath. A leap was a place where the barge tow-horse could jump the fence, and was usually reckoned to be 2.5 feet high.

The full text of the 1817 Act can be accessed from the River Lark homepage, or can be read here: River Lark Act 1817(Use your browser's 'back' button to return to this point.)

|

|

1818

|

One of the provisions of the 1817 Act of Parliament was to limit the top water marks on the River Lark Navigation. This was to prevent flooding of adjacent land. Top Water Marks were to be set 6 inches below the average bank level on the river, and the water level was not to exceed these marks, except in time of flood. The Commission were to hear appeals in this matter, and millers were not to be adversely affected by this regulation. Perhaps this provision was included because of past problems.

Reported in the Suffolk Chronicle for March 21st 1818, was the following:

"CONVICTION - On Wednesday week, the Magistrates at the Shire-Hall Bury, convicted Francis Brown and W. Hobbs, in the penalty of £4, for raising the water on the Navigation of the River Lark, higher than the top water marks lately established."

|

|

1821

|

In 1793 the Eau Brink Bill went before Parliament. Susanna Palmer had objected to the Bill, and managed to stave off the project for twenty years. In 1821 the Eau Brink Cut was finally made, which entailed digging a deep channel on the Great Ouse near Kings Lynn. This caused Great Ouse tributaries like the Lark to drain more quickly, thus losing water, and hindering navigation.

A new lock and staunch was now needed at Isleham, and work began to build them. It may well be that this was also the time at which Swales Reach was bypassed by a new channel.

|

|

J G Lenny's Map |

|

1823

|

As well as a new town map of Bury, J G Lenny also published a map showing the area for ten miles around Bury St Edmunds. On the canalised River Lark, the map shows the wharf just north of the Priory on Mildenhall Road. Evidence of this wharfage remained until the second half of the 20th century. It consisted of an "L" shaped cut from the Lark towards Mildenhall Road, which turned south before reaching the road. This allowed cargo to be unloaded without blocking the main river. The cut ended behind the old Maltings on Mildenhall Road.

|

|

1827

|

The South Level Drainage and Navigation Act set up the South Level Commissioners, who were given the right to dredge the River Lark below Swales Reach at Isleham, and to collect tolls from Prickwillow to Littleport to recompense them for the cost. They now took over the River Lark below Isleham.

|

|

1829

|

Susanna Palmer, the proprietor of the River Lark Navigation, died in 1829, aged 93. The Lark navigation now passed into the hands of Sir Thomas Gery Cullum. In practice he seems to have been managing it on her behalf for some years past.

|

|

1830

|

In 1830 the course of the Great Ouse was changed by drainage works by the new South Level Commissioners. Further work on the lower reaches of the River Lark also changed the course of the Lark navigation from its 18th century route. The old Roman four mile long canal from Isleham to Prickwillow was bypassed and began to dry up and disappear. A new cut was made on the Great Ouse, together with a new junction with the River Lark.

In 1830 Pigot's published their first Directory of Suffolk. This listed each town in the County, describing their history, local gentry and professions, and their tradesmen. Bury is described as "on the western bank of the river Bourne or Larke."

|

|

1831

|

Sir Thomas Gery Cullum the elder died in 1831, and his son, The Reverend Thomas Gery Cullum, now became the eighth, (and last) baronet of Hardwick, inheriting all his father's property and estates. It was the Reverend Sir Thomas Gery Cullum who carried out major improvements on the Hardwick House and Estate, and left his "TGC 19??" plaques on his new buildings and the improvements on the River Lark.

In April 1831 Joseph Priestley published his book entitled "Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and Railways, of Great Britain". He included an assessment of the River Lark, which can be read by clicking on Priestley's Assessment.

|

|

1836

|

Between 1833 and 1848 the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge published a series of articles on Historic Towns in 'The Penny Magazine'. An article in 1836 on Bury St Edmunds gave a snapshot of the town at the time, including the following;-

"The town of Bury is pleasantly situated on the river Larke, and from its delightful walks, clean streets, and well built houses, and from the urbanity of its inhabitants, forms as pleasant a country residence as any small town we know of."

"About a mile from the town the river Larke becomes navigable to Lynn, whence coals and other commodities are brought in small barges."

One important use of the River Lark was the transport of the heaviest of building materials. In a report which might remind us of the stone transported from Barnack to build the Abbey centuries earlier, The Bury and Norwich Post and Suffolk Herald of 6th April 1836 referred to the construction of a new Catholic church.

"A number of immense blocks of Ketton stone (many of them weighing 3 – 4 tons each) have been put on barges at Wansford to be used in building a large Catholic Church at Bury St Edmunds."

Ketton and Barnack are only a few kilometres apart, and Ketton stone is smoother than the shelly Barnack stone, which in any case, was largely worked out by now. Both sites depended upon dragging stone to the River Nene for access to markets.

|

|

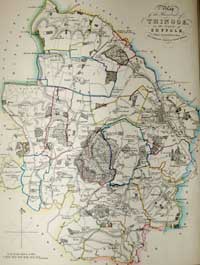

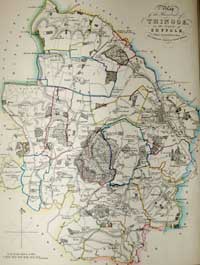

Extent of Thingoe Hundred 1838

|

|

1838

|

In 1838 John Deck of Bury published the work by John Gage entitled "History and Antiquities of Suffolk, Thingoe Hundred". This was a review of all the estates around Bury within the Hundred of Thingoe. This area contained 18 parishes and would survive as an administrative unit as Thingoe Rural District Council until 1974.

You can trace the course of part of the River Lark as far as it lay within the area of Thingoe. The Fornham Wharf is clearly marked together with Babwell Mill, Ducksluice etc.. The Cherry Ground Lock is not named, but it can be seen marked on Gage's map, just upstream of Lackford Bridge. This shows that some type of lock existed on the crescent shaped bend of the river before Cullum's improvements dated by his plaque of 1842.

Both the River Lark and Linnet are named on this plan.

The old Eastgate Bridge over the River Lark was pulled down in 1838. The East Gate itself had long gone, pulled down in 1763. The current bridge was built in its place, but not completed until 1840. Some alternative arrangements must have been in place while the bridge was being replaced.

|

|

Steggles Eastgate Bridge

|

|

1840

|

Some improvements were undertaken to Eastgate Street in Bury and the Marquess of Bristol subscribed to the works. The local building firm of Steggles built the white brick bridge which still crosses the River Lark. Iron railings were erected along the riverside there, reused from the Market Cross. This was the first time that there was no traffic actually fording the river. Up to 1840 there had always been a combination of bridge and ford in Eastgate Street.

By this time the Lark Navigation was owned by the Reverend Sir Thomas Gery Cullum, who had become the 8th baronet in 1831. As well as the improvements that he made to his own estate at Hardwick, Sir Thomas also set about renovating the Lark Navigation. His distinctive "TGC 18??" plaque was affixed to many of his buildings and improvements, both in Bury and on the river.

|

|

Built by TGC in 1842

|

|

1842

|

Some of Sir Thomas Cullum's major improvements to the River Lark were finished in 1842. These two cottages at the foot of Tut Hill in Fornham All Saints, were built by him, and have his "TGC 1842" plaque on their front wall. One may have been occupied by his lock-keeper/lengthsman, who managed this part of the river on his behalf.

The Cherry Ground lock was built by Sir Thomas, and once had a plaque stating "TGC 1842". This lock is now within the West Stow Country Park, and has been fenced off because the brickwork is crumbling away. It currently bears an Anglian Water sign calling it Cherry Tree Lock.

The Cherry Ground lock was a key part of the improvements to the river. It was built on a bend where the lock was fashioned into a crescent shape, much longer and wider than the usual locks on the Lark. It could hold 8 gangs of lighters at one time if necessary, lined up side by side. Such a lock justified a full time resident lock keeper.

So Sir Thomas Cullum also built River House nearby for the use of the lock keeper, or lengthsman, as he was also known. This was completely demolished in 1979 as part of the preparations for the opening of the West Stow Country Park to the public. The house had stood in ruins for years, and was unsafe. According to D E Weston, this house also bore the Cullum plaque, "TGC 1842".

|

|

1843

|

By 1843 the 80 commissioners appointed in 1817 had found their number greatly diminished by old age and death. Fifty new commissioners were appointed in 1843.

In the same year the founding act of the River Lark dated from 1699/1700 was published together with the Act of 1817, in a small book.

|

|

1844

|

By 1844 the River Lark navigation was thriving. White's Directory of Suffolk for 1844 recorded that barges went on a daily basis from Mildenhall Bridge to Bury St Edmunds and Kings Lynn. White's recorded that there was much greater traffic to and from Lynn than previously. Tolls had been cut from 7/- and 8/- a ton to 4/6 and 5/- a ton by Sir Thomas Gery Cullum, who was also responsible for major improvements along the river.

|

|

1845

|

Records show that some 10,000 tons of goods and coals were sent from Kings Lynn to Bury St Edmunds by barge in 1845. By 1852 this trade would have dwindled to almost nothing.

|

|

First train to Bury |

|

1846

|

The River Lark navigation enjoyed its last 12 months of prosperity until disaster arrived at Bury St Edmunds in the shape of the railway.

In December, 1846 the long hoped for railway line arrived at Bury St Edmunds from Ipswich. A railway line now linked London, Colchester, Ipswich, Stowmarket and Bury St Edmunds. In December, 1846, when the first 90 tons of coal arrived in Bury by train, its price fell by ten percent. It arrived to temporary platforms just east of the bridge over Out Northgate Street, and the current station had hardly been started. Nevertheless there were street celebrations and fireworks to welcome this great event. The railways gave the town an easy export route, as well as bringing goods in cheaper. The old established brewing and malting industry could now be joined by other newer undertakings.

Merchants who had relied upon the Lark Navigation for coal, could now import it by rail. Coalyards would now be installed on the Station Hill in Bury to receive the rail shipments.

|

|

1847

|

In 1847 men 'raising gravel for ballast' for the barge traffic on the navigable River Lark, found skeletons and numerous cremation urns at West Stow. The term ballast probably referred to its use for road making purposes. It was transported away by barge.

|

|

1848

|

A railway link was established from Cambridge to Newmarket, but there was as yet no link to Bury from this direction.

Since 1831 the Reverend Sir Thomas Gery Cullum had been proprietor of the Lark Navigation Company, inheriting it from his father, also called Sir Thomas Gery Cullum. This included the wharfage and associated businesses on the Mildenhall Road, just outside the boundary of the Borough of Bury St Edmunds at the time. Both Sir Thomas the elder and Sir Thomas the younger had invested large sums of money and enthusiasm into the River Lark.

The railway had already caused a drop in river traffic. Cullum could clearly see that the railways would result in a continuing loss of trade on the canals, and he needed to take some action to alleviate the situation. He opened negotiations with the Eastern Union Railway Company to try to guarantee himself some income from the Navigation.

Bury St Edmunds corporation finally got wind of Cullum's intentions.

On December 25th the Town Clerk of Bury wrote to Cullum to ask him to cease negotiations with the Railway, and to meet a deputation from the Council. Cullum replied that it was now too late for him to withdraw from a conclusion of his agreement with them.

|

|

1849

|

In this year the Eastern Union Railway company agreed to pay the Reverend Sir Thomas Cullum £500 a year to let the Lark Navigation decay for ten years. Cullum also agreed that he would not lower the river tolls in order to compete with the railway, and that the tolls, less commission, would be paid to the Railway Company. The agreement started on 1st January 1849, and despite the protests of the Bury Corporation, the deal was done. The corporation's legal advice was that this was contrary to the original Navigation Act.

However the river continued to be used to haul coal to the Fornham Wharf until 1890. The cut from the River to the Wharf survived until the 1970's, and the river was known as the Coal Rivers by local boys into the 1960's. By the end of the 20th century the cut was filled in to provide parking for a transport and haulage business. Only a small ditch remains to collect outflow from the surface water drains on the Mildenhall Estate, and deliver it to the River Lark. Even this ditch is diverted several yards to the north of the course of the original cut.

|

|

1850

|

The River Lark was sometimes called the River Jordan at this time, because of the practice which had arisen of performing large scale baptisms in its water. This was mainly carried out at Isleham Ferry. The most celebrated of these baptisms may have been that of Charles Haddon Spurgeon, which took place on May 3rd 1850. The event itself was not particularly noteworthy, but Spurgeon himself went on to become a great evangelical preacher, and attributed this to the power of his baptism. He wrote about it as follows:

"The wind blew down the river with a cutting blast as my turn came to wade into the flood; but after I had walked a few steps, and noted the people on the ferryboat, and in boats, and on either shore, I felt as if heaven and earth and hell might all gaze upon me, for I was not ashamed, then and there, to own myself a follower of the Lamb. My timidity was washed away; it floated down the river into the sea, and must have been devoured by the fishes, for I have never felt anything of the kind since. Baptism also loosed my tongue, and from that day it has never been quiet."

Baptisms were regularly carried out at Isleham up to the early 1970s.

|

|

Dunnell's Maltings of 1851 |

|

1851

|

The coming of the railways had a profound effect upon the commerce of the River Lark. This navigable river extended from the Great Ouse river, through Mildenhall and upstream as far as the Fornham Wharf. This wharf was within the parish of Fornham All Saints, upon land owned at the time by Sir Thomas Gery Cullum.

Much of the land at the Fornham Wharf had been coalyards, and most of the tonnage on the river had been coal. The Ipswich to Bury railway line had been delivering coal right into Bury St Edmunds at Northgate Street since December 1846. Thomas Ridley had rented a coal warehouse from Sir Thomas at Fornham Wharf, but he no longer required its use. Sir Thomas probably did not have the money, or the inclination, to redevelop the site himself, so he let it to Robert and John Dunnell, who built a large new Malt House on the site.

This is what the White's Directory of Suffolk for 1855 said about it;

"Sir T R Gage, Bart, is lord of the manor (of Fornham All Saints), but part of the soil belongs to Sir T G Cullum, Bart, on whose estate, at the south-west angle of the parish, 1 mile N. of Bury, is a commodious Wharf, at the termination of the Lark Navigation, ... and a large Malting House, built in 1851."

The Directory for this parish failed to identify a maltster, but a James Footer was recorded as a "carpenter, Wharf", presumably indicating that his business took place at the Wharf.

The wharf was served by a cut from the River Lark which then turned 90 degrees to run parallel to the Mildenhall Road. This cut survived in a silted up form until the 1960s, but was filled in to provide land for development.

Nothing now remains of the Wharf, which now lies beneath the UPS distribution depot, but the Maltings was used for this purpose until at least the 1960s. Later it became a furniture warehouse, finally known as Kingsbury's, but in 2008 it has stood empty for several years. Some iron ties at the northern end of the building still display the inscription, "TGC 1851".

|

|

1852

|

By 1852 most of the old river trade had transferred on to the railway, even though the railway from Bury ran to London via Ipswich. This was completely the opposite direction to the coal trade which had flourished by river to Kings Lynn. A few businesses along the river therefore chose to continue to be supplied by river. These would have included the watermills, some of which used steam engines by now, and possibly the large maltings located on the Fornham Wharf.

|

|

1853

|

In 1853 Sir Thomas Gery Cullum mortgaged many of his assets connected with the River Lark Navigation. He mortgaged the Fornham Malting estate, raising £8,000 on it. It consisted of a malthouse, storehouse, granary, stable, yard, pumps, cisterns, kilns and furnaces. Robert and John Dunnell continued as sitting tenants of the Maltings.

Sir Thomas also raised mortgages on the nearby Friary Estate and Tollgate Estate.

The Bury St Edmunds Corporation continued to be worried about the state of the River Lark. They took Counsel's Opinion on the legality of Sir Thomas's agreement with the Railway Company. Counsel wrote that, "the agreement is altogether illegal and void." He also gave the opinion that it was illegal for Sir Thomas to have made improvements up to Fornham Wharf without continuing to Eastgate Bridge, the legal end of the Navigation. However, it required an aggrieved party, such as a shareholder, to take the matter to the Courts.

The Council wrote to the Clerk of the Navigation Company to obtain information about the agreement and the income now being received. The Clerk and Solicitor was John Greene of Bury St Edmunds, and he gave some information but refused to give other details.

One piece of interesting information emerged when the corporation asked for the toll structure by the ton of coal. The toll for coal brought from Mildenhall upriver to Fornham Wharf was set at 4/2 per chaldron. John Greene calculated that this was equivalent to 3/2 per ton of coal. In fact, if a chaldron was actually equal to a short ton, and slightly less than a long ton, then the toll should have been calculated as either 4/2 or 4/8 per ton, depending upon the definition of a ton at the time.

Sir Thomas Cullum replied to the corporation's complaints about the state of the river thus:

"the sluggish state of the stream arises from want of trade upon it, not from any neglect by the proprietor." Cullum was 75 by now, but still active in business.

|

|

1854

|

The council tried to press Sir Thomas Cullum to extend the Lark Navigation up to the Northgate Railway Bridge in Bury St Edmunds, despite its failing profitability.

When the existing railway link from Cambridge to Newmarket was extended to Bury St Edmunds in 1854, the price of coal in Bury became even cheaper. At Bury's Northgate Station further works had to be carried out to accommodate the new line from the west, but coal could now arrive from the Midlands via Cambridge, or by sea via Ipswich.

This prompted Sir Thomas to offer to sell the Lark Navigation to the Council of the Borough of Bury St Edmunds. They did not take him up on it.

|

|

1855

|

White's Directory of Suffolk for 1855 noted that:

"In consequence of an arrangement between Sir T G Cullum and the Railway Company, the traffic on the Lark Navigation is now much diminished."

During this period of the sudden decline of the River Lark navigation, Sir Thomas Gery Cullum died, aged 77, on February 3rd, 1855. He had made many improvements to the river in the 1840s, but the new railways had largely destroyed the barge trade.

In December 1855 Thomas Prentice proudly announced that his new Railway Wharf was now in operation to bring best Staveley coal to Bury St Edmunds for 19/6 per ton. Delivery in town would cost another 1/- a ton. Railway Wharf was not on the River Lark, but was his name for his new coal depot on Station Hill, served by rail, not by water.

|

|

1856

|

Following the death of Sir Thomas Gery Cullum in 1855, his widow, Lady Ann Cullum, was now ready and willing to sell the Lark Navigation to the Borough Council of Bury St Edmunds for £8,000. By this date the river was only used for trade up as far as Lackford.

The Borough Council had John Croft draw up plans for an extension of the Navigation up to Northgate Railway Bridge, and published a prospectus for a new company to manage and improve the river. The Bury St Edmunds Navigation company tried to raise £20,000 by issuing 2,000 shares at £10 each, but the project failed, with few, if any, takers.

|

|

1857

|

The competition presented to the River Lark by the railways can be illustrated by the example of the Borough Surveyor for Bury St Edmunds, when he sought quotes for bringing in roadstone to Bury St Edmunds. He found that he could get stone delivered from Ipswich by rail for 4/9 a ton. Stone brought from Kings Lynn by river would cost 4/6 a ton, 2/3 was asked for tolls, and a further 1/- for delivery from Fornham Wharf to the town. This made a total of 7/9 delivered by river and 4/9 by rail.

|

|

1858

|

Lady Ann Cullum had used a Bury St Edmunds auctioneer and land agent, called Henry Newson in her attempts to sell off the River Lark in 1856. In 1858 she made a conditional sale of the Navigation to Henry Newson and James Lee, the latter a timber and coal merchant and Maltster of 27 Risbygate Street in Bury St Edmunds. The price agreed was £7,050. payable in full within a set term.

|

|

1859

|

Following the agreement made 10 years earlier with the railways, the Lark Navigation was now in a badly decayed state. The agreement now expired in 1859. This meant that any new operator could reduce tolls to compete with the railways, but would need to spend money to repair the dilapidations of the last decade. Henry Newson and James Lee could now try to make the river a going concern again.

The Bury Paving Commissioners had adopted significant provisions of the Public Health Act of 1848 and the local Government Act of 1858 relating to sewers, drains and privies. New houses in Bury now had to be built with drains and a water closet. The Commission had established a sewage works at the Tay Fen, but in the 1850's it was causing concern because of smells and the usual problems of sewage disposal. However, most people still had nightsoil collected by cart, or stored it in the yard for sale to farmers. Something was needed a bit further out of town and a site was identified at Bell Meadow.

|

|

1861

|

The partnership of Newson and Lee had failed to pay the agreed price for the Lark Navigation, and so, in 1861 ownership reverted to Lady Ann Cullum.

|

|

1862

|

Still desperate to sell the Lark Navigation, Lady Ann Cullum had it auctioned off in London. The Navigation was sold for £4,500, half its original build cost, to James Lee, a local coal and timber merchant. He planned to bring in coal cheaper than the railway, but first it needed a massive investment in the canal. Lee died on September 8th, 1862, before anything came of his plan.

James Lee left the Navigation to three men whom he must have thought were most likely to make something of it. These were William Biddell of Hawstead, Robert Boby of Bury, and John Jackson of Fornham. The first two men repudiated the bequest, leaving John Jackson to be sole beneficiary.

|

|

1863

|

In 1863 a sewage works was opened at what is now called Bell Meadow in Bury. It was the first attempt in the town to deal with the collective disposal of foul water. It soon led to complaints. Bell Meadow is adjacent to the River Lark near the Tollgate Inn.

Meanwhile a civil engineer called G R Burnell published a full and detailed survey of the River Lark, and a study of proposed improvements. It seems that James Lee had commissioned this before his death.

Burnell's study stated that he had made his calculations for income on the assumption that Bury St Edmunds could consume 25,000 tons of coal a year. He also expected to gain trade from the Clunch lime being extracted at Isleham, and from the flints being dug at Icklingham for the repair of roads in the fens. He also expected that the corn trade from farms along the river could be increased.

The works required to extend the river included a reduction in the water surface from Babwell Friars Clough to Northgate by 18 inches, the height of the Babwell Clough. This would be achieved by dredging. All of the cloughs and staunches were to be removed.

He wrote that:

"Nowadays the system of cloughs and staunches is entirely abandoned on any river destined to support a constant navigation, as it is only capable of producing a temporary flush of water."

He planned to use dredgers to deepen the river bed instead. He had calculated that from Northgate to Mildenhall Sluice the river had a fall of 71 feet 4 inches. He would accomodate this by 13 locks, and would abandon seven staunches.

John Jackson, now the sole owner of the river by inheritance from James Lee, does not seem to have adopted this report.

|

|

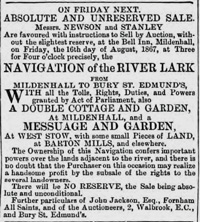

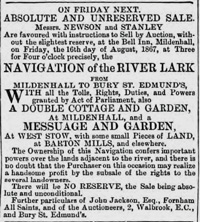

Sale of River Lark Estate |

|

blank |

|

1867

|

In August 1867, John Jackson started to sell off the assets of the Lark Navigation. The cottages and weighbridge were sold at auction. There was little interest and it proved difficult to sell.

|

|

1868

|

John Jackson now sold the Fornham Wharf back to Lady Ann Cullum for £600. He proceeded to sell off all the land belonging to the River Lark Navigation Company, retaining only the river and its towpaths.

|

|

1871

|

On July 13th, 1871, John Jackson finally sold off the remaining rump of the River Lark Navigation to Charles Kirby of Great Cornard for £55.

A bill was introduced into Parliament called the Ely and Bury St Edmunds Railway Bill, which included a clause designed to close down the Lark Navigation. Following protest from Bury St Edmunds corporation, this clause was omitted.

|

|

1875

|

Charles Kirby sold the River Lark Navigation rights to Frederick Woodbridge of Kentish Town for £60. Woodbridge seems to have done nothing for the river.

|

|

|

Bad weather July 1879 |

|

blank |

|

1879

|

Very wet weather meant that this was a year of disastrous harvests, some fields were not finished until October. The bad weather holding up the harvest is illustrated here by flooding in the Abbey Gardens in July, when the showmen's gathering was flooded out.

|

|

1882

|

The well known footbridge across the river Lark, located in the Abbey Gardens, was built in 1882. It was built for the use of scholars at the new home of the King Edward VI Grammar School, which was being built at the time in the Vinefields.

The Mildenhall Almanack for 1882 reported that:

"The River Lark as a water highway, at least the upper portion of it is practically closed. Within a few years the traffic extended to Fornham, now, above Mildenhall, a barge is never seen. The whole course of the river is choked with weeds, on which, during floods, heavy deposits of soil have accumulated, which renders navigation impossible..."

At Bury St Edmunds, public opinion also was pressing the council to do something about the river.

|

|

1883

|

Following public pressure, the Mayor of Bury St Edmunds, Cllr Thomas Ridley, authorised Mr Scott of the council to seek out the present possessor of the plans and books of the Lark Navigation and to purchase them on behalf of the council if they could be obtained at a reasonable price.

The council was considering not only the repair of the existing navigation, but its extension from the Fornham Wharf as far as the railway bridge over the river behind the ruined St Savious Hospital. It would take another two years before serious progress was made.

|

|

1885

|

In January 1885, Mr Scott reported to the council that he had found a civil engineer, called Mr Gilmour, who would manage the setting up of a new company to carry out the works. He required a guaranteed return of 3 or 4% a year, which he wanted the council to underwrite. The council, of course, wanted to limit the input of its ratepayers' money.

Luckily for the council, the Hervey family of Ickworth decided to become involved. Both the Marquis of Bristol, Frederick William John Hervey, and Lord Francis Hervey, MP, supported the proposals for a new and improved River Lark Navigation. However, outside interests now owned the navigation rights, and an impossible price of £10,000 had been mentioned to buy them back. The Herveys realised that legislation would be needed to get anything done at a reasonable price.

|

|

|

West Stow pumping station |

|

1886

|

Some 112 acres at West Stow were purchased by the Borough Council in 1885, for a new sewage farm to be constructed to serve the town of Bury St Edmunds. Building took place from 1885 to 1887. This would replace the works built in 1863 at Bell Meadow in Bury. Like most sewerage schemes, it relied on gravity to provide the flow, and so the pipes were laid, as far as possible, along the river valleys. A pumping station was built by the River Lark at West Stow, at the end of the line, to pump effluent up into the site from a tank at the end of the pipeline. This is the only building now remaining from this work. The expression sewage 'farm' came about because 20 acres of the site were to be used to grow crops such as tomatoes and black currents to be irrigated from the outfall.

Several improvements and changes were needed within a decade to improve its operation.

However, ownership of this land adjacent to the river Lark, raised the possibility of river improvements at the same time.

|

|

1888

|

In 1888 Parliament passed the "Railway and Canal Traffic Act". His Lordship the Marquis of Bristol and the MP Lord Francis Hervey had a hand in drafting this piece of legislation. It ensured that Canal Companies had to make proper returns to the Board of Trade, and clause 41 dealt with decayed waterways:

" Inspection of canals: Whenever the Board of Trade are, through their officers or otherwise, informed that the works of any canal are in such a condition as to be dangerous to the public, or to cause serious inconvenience or hindrance to traffic, the Board of Trade may direct such officer or other person as they appoint for the purpose to inspect the said canal and report thereon to the Board of Trade, and for the purpose of making any inspection under this section the officer or person appointed for the purpose shall, in relation to the canal or works to be inspected, have all the powers of an inspector appointed under the M1 Regulation of The Railways Act 1871."

|

|

1889

|

With the legislation in place which could force a reluctant canal owner to bring the navigation up to proper standards at considerable cost, the owner of the Lark Navigation was willing to dispose of his asset, which had now become a potential liability to him. In June 1889, Mr F Woodbridge sold the Lark Navigation to the Marquis of Bristol and the Mayor of Bury St Edmunds for just £26.5.0..

They were acting on behalf of the new company which was in the process of being formed, to be called "The Eastern Counties Navigation and Transport Company Limited", or the "ECN & TCL", as their new lighters would soon be blazoned.

The Herveys ensured that the first enquiry by the Board of Trade under the 1888 Railway and Canal Traffic Act was held into the River Lark. In August of 1889 the Board of Trade Enquiry opened in Bury St Edmunds. Both their Lordships were in attendance as were representatives of the Bury St Edmunds Borough Council and all the riparian owners on the river. There were no objections to the ECN & TCL taking over the running of the navigation and its subsequent improvement.

Things moved swiftly and improvements to the river Lark at Mildenhall began straight away in August 1889, as did the construction of the new wharf at St Saviours. The dredging and canalisation of the river from Fornham Wharf to St Saviours had already begun in July 1889.

Plans were drawn up for a new bridge to carry the Fornham Road by the Tollgate Inn, and for a new lock just upstream of the bridge.

The contractor was Mr James Wilson.

|

|

Lock repairs Mildenhall 1889 |

|

blank |

In October a steam dredger was in use on the Mildenhall section, and the locks there were being repaired. By November, the river was nearly completely excavated from Mildenhall to Barton Mills. "In many parts the river is 50 feet wide and 6 feet deep" wrote William Howlett, who recorded progress on the river as a correspondent for the Bury Free Press and other local newspapers.

Despite all this progress on the river, the Eastern Counties Navigation and Transport Company Limited was only formally established in November 1889. This haste may have contributed to the disputes with the builders which erupted in the next two years.

On December 7th the Company called a public meeting at the Guildhall in Bury St Edmunds, to offer its shares to the general public. Lord Bristol and Lord Francis Hervey had already bought £1,000 of shares each. Other notable shareholders already in place were the Bishop of Bath and Wells, (Lord Arthur Hervey), and Mr C Quilter MP. The Mayor announced that the company had appointed a Mr Thomas as its General Manager.

|

|

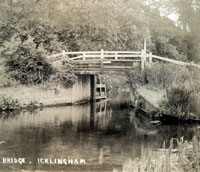

Icklingham Bridge c1905 |

|

1890

|

By January 29th William Howlett reported the progress on works from Isleham to Bury. From the Lee Brook junction, where work started, to Cindall Hills old ferry house, the work was partially complete. The dredger had increased the depth at the West Row ford to over 5 feet, so people were demanding a bridge. The Turf Lock at Mildenhall had been repaired.

At Icklingham the Temple Bridge was awaiting reconstruction. Because the intention was to use steam tugs to replace the horse for towing lighters, some bridges needed to be raised to allow clearance for the funnels of the tugs. Lackford Bridge was already being heightened.

The Cherryground Lock, which had been built by The Reverend T G Cullum in 1842, could hold 8 whole gangs of barges at one time. Repairs had been carried out. Locks at Fullers Mill, Flempton and Chimney Mills had all been repaired. They were still awaiting new lock-gates. However, at Ducksluice lock at Fornham, the lock was complete with gates.

Despite this good progress, there were still seven miles of the river which was as yet untouched, and 15 locks and gates remained to be fixed.

William Howlett had been so impressed with the work of the navvies in the cold of 1889, that he had organised a public subscription to give them all a meal of roast beef and plum pudding. The river improvements had great public support, and the dinner for 100 men took place at The Red Lion in Icklingham on 21st February 1890. Fishermen were pleased that the works were carried out with great care for the fish.