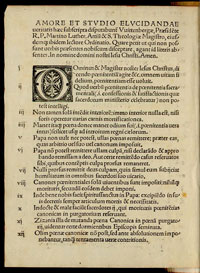

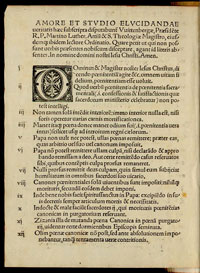

Martin Luther's 95 theses

Quick links on this page

Friends Meeting House 1750

Catholic Chapel 1760

Catholic Relief Act 1791

Ebenezer Chapel 1800

Primitive Methodists 1820

Oxford Movement 1833

Catholic & Rehoboth 1838

Plymouth Brethren 1853

Wesleyan Chapel 1878

Salvation Army 1890

Bottom of Page 1897

|

Alternative and Non-Conformist Religion

After 1700

|

1700

|

In 1685 Louis decided to outlaw Protestantism in France, which had been tolerated in selected cities since the Edict of Nantes in 1598. After he revoked the Edict, Protestants were persecuted in France, and hundreds of thousands went abroad. About 50,000 came to England.

|

|

1701

|

The Reverend John Beart became pastor of the Independent Congregation in Bury St Edmunds. He continued to take the Independent cause to Chevington and the villages south of Bury.

By 1701 Parliament had become desperately worried about the future of the monarchy. William and Mary had produced no heirs. Although Mary's sister, Anne, could succeed to the throne, she had also failed to produce an heir who had survived beyond childhood. In order to settle this issue in advance, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement of 1701. This Act settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns and thrones on the Electress Sophia of Hanover (a granddaughter of James I) and her non-Roman Catholic heirs. The other surviving Stuarts were all Roman Catholics, and they were excluded by this Act.

|

|

Queen Anne 1702-1714

Queen Anne 1702-1714

|

|

1704

|

In medieval times the practice of giving one tenth of the production of agricultural produce to the church had already been well established. Monasteries erected tithe barns to hold the grain, and much of this had supported the clergy as well as some being redistributed to the poor. By 1547 King Henry VIII had confiscated the payment of tithes to the catholic church, and often had sold the rights to new lay landowners or "lay impropriators". What was left was payable to the Church of England. Various means arose over the years to avoid church tithes, and the result of all this was that by 1704 most country parsons were left with only a very small income, while the right to tithes were seen to profit already wealthy landowners.

Gilbert Burnett, the Bishop of Salisbury, persuaded Queen Anne that help was needed, and this resulted in 'Queen Anne's Bounty for the Augmentation of the Maintenance of the Poor Clergy.' All the royal revenues from First Fruits and Tenths would be paid to the clergy.

This act would reignite the enforcement, and the resistance to, tithe payments right up to the late 20th century.

|

|

1707

|

The Act of Union joined England and Scotland, ensuring that Scotland could not install a rival Stuart as King upon Queen Anne's demise. This meant that after Queen Anne's death, Scotland would also be subject to the 1701 Act of Settlement.

|

1708

|

A new purpose built church was completed for the Congregationalists in Whiting Street. The building itself was built between 1697 and 1708 making it the first non-conformist building in Bury St Edmunds. The facade later added in 1866 makes the church we see today look Victorian. However, if you look at the side of the building the original meeting house architecture is still visible. It can also be seen within the interior once you look past the modifications of the Victorians.

At the time this building was known as The Independent Chapel. The website https://burystedmundsurc.org.uk/history/ has a description of this first building:-

"That building was almost square with a high central pulpit to emphasise the high regard of the Ministry of the Word.

As numbers grew, the building was extended: firstly a gallery at the rear, then the sides and finally an extension behind the pulpit to include an organ loft."

|

|

|

Presbyterian Chapel

|

|

1711

|

The Unitarian Meeting House was built in Churchgate Street for local Bury presbyterians, and remains one of Bury's more remarkable buildings. It replaced an earlier Meeting House built for the Presbyterians. Unitarianism was not embraced until 1801.

|

|

1714

|

The Act of Settlement of 1701 had named the Electress of Hanover, Sophia, as heir to the throne, together with her Protestant heirs.

Sophia died on 8 June 1714, before the death of Queen Anne on 1 August 1714, at which time Sophia's son duly became King George I and started the Hanoverian dynasty. He was 54 years old.

|

|

1718

|

Between 1715 and 1718, Dr John Evans collected details of every Dissenting congregation in England and Wales. Since 1689 Dissenters could worship in public, resulting in a large increase in their numbers. Bury now had 900 Protestant Dissenters by 1718 compared to 167 in 1676. Haverhill had 250 compared to 30 in the Compton census. Clare had 400 compared to a very high 300 in 1676. Sudbury had 400 now and 100 in 1676.

Walsham le Willows had grown from only 3 to 400, and Wattisfield from 49 to 350.

Numbers attending Anglican services had declined, but under the Toleration Act of 1689, people could now avoid church attendance altogether if they wished.

|

|

1731

|

Until 1731 Hugh Owen was the only Catholic priest in Bury St Edmunds. Dr Francis Young has established that "in that year a Benedictine monk, Alexius Jones, arrived to serve as chaplain to the Bond family, who lived in Eastgate Street in a house that was sadly knocked down during road-widening in the 1920s....

Jones posed as a tutor to the Bonds’ son Jemmy but officiated at the Mass in a secret chapel in the Bond household."

The Catholic Bond family had moved to Bury St Edmunds in 1675, following the marriage of Mary Bond to Sir William Gage of Hengrave. Her brother William had married Mary Gage at the same time.

|

|

1733

|

The underground Catholic Mission to Bury St Edmunds was ministered to by the secular priest, Hugh Owen, (sponsored by the Short family), and, to a lesser extent, by Alexius Jones, the Benedictine Chaplain to the Bond family. Dr Francis Young has established that another Benedictine appeared on the scene in 1733, called Francis Howard. "Howard was chaplain to the Gages at Hengrave Hall but was frequently in Bury, because the Gages owned a townhouse in Northgate Street (now the Farmers Club)."

Also, " That year a devastating smallpox epidemic swept through the town and anyone who could afford to do so fled Bury; Sir Thomas Gage and Mr Bond fled to Thetford, ostensibly on a fishing trip, and took Jones and Howard with them."

The ageing Hugh Owen was left to minister to dead and dying Catholics.

|

|

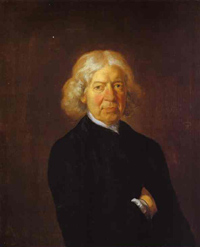

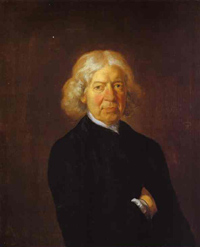

John Kirby by Thomas Gainsborough, 1753

|

|

1735

|

In August 1735 John Kirby published his book called "The Suffolk Traveller". He would follow this up in 1736 by publishing a one inch to the mile map of the county, followed by a half inch scale in 1737.

One section in the book covered the church:-

"The ecclesiastical government is under the Bishop of Norwich, it being part of that see....it is divided into two archdeaconries, viz Suffolk containing the Eastern parts of this county, and Sudbury including the Western parts. These two archdeaconries are subdivided into 22 Deaneries.......The Deaconries in the Archdeaconry of Sudbury are, Sudbury, Stow, Thingoe, Clare, Fordham, Hartsmere, Blackbourne and Thedwastry...."

"The civil government of this county is in the High Sheriff, for the time being. The division of this county ...was formerly divided into the Geldable and the Liberties of St Edmund, St Etheldred, and St Audrey; but the present division is into the Geldable and the Franchise or Liberty of St Edmund, each of them furnishes a distinct Grand Jury at the Assizes..."

A Freemasonry Lodge was established at the White Horse Inn on the Buttermarket. This inn was superceded by Bullens haberdashers in 1870, and in later years served as Purdey's Coffe Shop, Palmers Restaurant, and is now a travel agency and Burger King restaurant.

|

|

1736

|

Bury St Edmunds received some fame through its MP, Lord Hervy. He was asked by the Whig Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, to pilot the Quakers Bill through Parliament. This bill aimed to relieve the Quakers from some of their legal burdens, for which many had suffered heavy fines and long prison sentences over the years.

Unfortunately the established church were strongly opposed to it, led by the Bishop of Salisbury, who wrote a pamphlet called "The Country Parson's Plea against the Quakers Bill for Tythes." Lord Hervey wrote a reply, called "The Quakers reply to the Country Parson's Plea". He stoutly defended Quakerism, although it was not his own calling, and praised their piety, their thrift and industry, and their support of their own poor.

Lord Hervey had done his job well, and got the Bill through the House of Commons only to be defeated in the House of Lords. Bury Quakers as well as those in the rest of the country, got no relief from tithes until the late 19th century.

|

|

1741

|

The Catholic priest, Hugh Owen, died in 1741. He had ministered to Bury's Catholics in various back room locations, like the Greyhound and the Angel, since 1691, supported by the Short family. The Gage family of Hengrave, and of Northgate Street in town, had their own Catholic chaplain, Francis Howard, who had to take over these duties, " presumably because there was no-one else available" (Francis Young). Howard himself would die in 1755.

|

|

1744

|

At Westley, the church of St Thomas of Canterbury, (Thomas a' Beckett) suffered severe damage from a storm. The church lost its steeple, and apparently this was not replaced. Further storm damage in 1789 would be attributed to its long decline until by 1834 it would be closed as beyond repair.

|

|

Quaker burial ground

|

|

1748

|

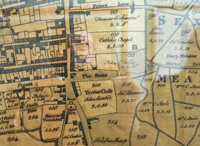

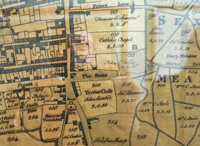

In 1748 Thomas Warren published his plan of Bury St Edmunds as it was at the time. The extract shown here has been re-aligned to match the modern mapping system whereby north is shown at the top of the map. Warren's original had east at the top.

The Quaker burial ground can be seen in Well Street, labelled as "Q'rs Burial Ground", and a better view can be seen by clicking on this thumbnail. The location is shown adjacent to the "W" of Well Street.

This map also showed the Quakers' meeting house in Long Brackland, whereas by the time his son published an update in 1776, it had moved to its current site in today's St Johns Street.

|

|

New Quaker Meeting House

|

|

1750

|

A Quaker, John Drewett purchased several old decaying tenements in Long Brackland some distance closer to the town than the existing Friends Meeting Place. The intention was to build a new Quaker Meeting House and bring the Burial ground and meeting place together. Warren's map of 1746-47 showed the old Quaker Meeting house as much further down Long Brackland than today's site, and its burial site was in Well Street. The new Meeting House was completed in 1751, and the whole area was conveyed in Trust to the Quakers in 1752.

|

|

1752

|

Until the end of 1751 the year began in Britain on Lady Day, the 25th March. If March was therefore counted as the first month, this explains why September was the seventh, October, the eighth, November the ninth and December the tenth month, as in their names.

In 1752 England and Wales adopted the Gregorian Calendar and an 11 day correction was needed to bring Britain into line with Europe. The day after September 2nd became September 14th 1752. The new year now began on January 1st. This new system had been in use in the Catholic world since 1582 when Pope Gregory had fixed the months of unequal length, and refined the calculation of the leap year to keep local time in step with the movement of the planets.

At Bury the Quakers officially took over their newly built Meeting House in St Johns Street, where it remains today. It had been in progress since John Drewett bought the land in 1750 for this purpose. This fine building remains today, although it was then in the street called Long Brackland, becoming called St Johns Street in the 19th century. It could hold 500 people and has had a Suffolk white brick facade added on the east side in the mid 19th century.

Meanwhile Roman Catholicism, whilst illegal, was quietly practiced in Bury. Sometime in the 1750's a large extension on stilts was added to a substantial red brick house in Southgate Street, butting on to St Botolph's Lane. It seems that this was used by John Gage, a jesuit priest, as a chantry chapel to say the Mass.

|

|

1755

|

Bury had a small but active Catholic population at this time, but no permanent place of worship and had to rely upon the Chaplains of gentry families for a ministry. Both Francis Howard (Gage chaplain) and Alexius Jones, (Bond chaplain) died in 1755, leaving no Catholic Mission in Bury St Edmunds.

At this point the Jesuits returned to influence in Bury when John Gage saw this opening. John Gage was the brother of Thomas Rookwood Gage of Coldham Hall. John Gage had established a chapel in his mother Elizabeth Rookwood’s house in

Southgate Street in 1753, and now wanted to take over the Bury Catholic Mission. The Short family, always against the Jesuits, tried to set up a rival Dominican Mission, but Gage had greater financial resources.

|

|

1757

|

John Wesley travelled through the area to Norwich on many occasions, often staying at Lakenheath, a village with a revivalist tradition. In 1757 he filled the newly built "preaching house" there.

|

|

John Gage's house

|

|

1760

|

Despite all the new dissenting religions, the Roman Catholics still numbered about 158 in Bury at this time. They were always thought of as recusants, rather than dissenters. Although the Mass was still technically illegal, Father John Gage, a Jesuit, built himself a house and chapel in Westgate Street in 1760/1761. He was brother of the owner of Hengrave Hall, and enjoyed status and some wealth.

Gage had worshipped at a chapel in his mother's house in Southgate Street since he set up the chapel there in 1753. In 1755 he wanted to take over the Catholic Mission to Bury, and because he benefitted from superior funding, he was able to complete his permanent purpose-built chapel in Westgate Street which still stands to this day. The chapel was built as an extension to the rear of house.

|

|

John Gage's chapel

|

|

blank |

Dr Francis Young has described this building as follows: "John Gage’s chapel is truly remarkable: it is one of the first semi-public and purpose-built Catholic chapels in England. Although the penal laws had ceased to be enforced by 1761, Catholics remained on the alert. As recently as 1745, all horses and firearms had been confiscated from Catholics as a result of the Jacobite rising, and as the Gordon Riots of 1780 would prove, anti-Catholic mob violence was far from over. Yet John Gage felt safe and confident enough in Bury to build a chapel behind his house which, although invisible from the street, was quite obvious from the rear.

John Gage’s chapel was a pattern for other chapels built after the Second Catholic Relief Act of 1791, which allowed the licensing of privately owned chapels. But how was it that, thirty years before his chapel was legal, John Gage felt safe enough to build it? All the evidence suggests that Bury was an unusually tolerant town towards Catholics; indeed, it was such a good place for Catholics to live that they chose to move there."

The picture here is a priest's eye view looking back towards the house, which was the access way at the time.

|

|

1761

|

The origin of Methodism in Haverhill seems to date from this year when a barn in that town belonging to John Adams was licensed for itinerant preachers.

|

|

1762

|

John Wesley, the great Methodist preacher, recorded in his diary that he preached in a barn in Haverhill. He also visited Bury 17 times over several years from about 1755 onwards. At Bury he would preach in private houses, one of which was the home of Hannah and Elizabeth Jervers in the Horsemarket, which today is called St Mary's Square.

|

|

1767

|

Audits of the local Catholic populations were carried out in 1680, 1705, 1744, 1767 and 1780. The period of Roman Catholic persecution is often referred to as the 'Penal Times' and lasted from 1534 to 1778. Although the measures were often harsh, many anti-Catholic laws were not always strictly enforced, and this was often the case in Bury St Edmunds. By 1767 local Catholic recusants were 2.5 percent of Bury's population, compared to 0.97 percent nationally. Catholics found it easy to live here, and were never seen as a threat. Local Catholic gentry families like the Gages of Hengrave and the Rookwoods of Coldham Hall were all respected by this time.

|

|

1773

|

In 1773 George Paul (1740-1828) and his wife came to Bury St Edmunds to set up as an ironmonger. The family originated from Burwell. Like many businessmen at the time, he was a religious dissenter, and they were welcomed into the close knit Independent Church. (Later this became the Congregational Church.) The church also acted as a banker in that church accounts recorded that £20 cash was lent to George Paul at 5% interest. George became a Deacon, as did his son, George Paul II (1776-1852) who preached throughout South West Suffolk, meeting all the leading corn growers and maltsters. Their descendants would leave Bury and, in 1877, found the firm of R & W Paul, the well known malting enterprise at Ipswich.

|

|

1780

|

In 1780 the house in the Horsemarket, (St Mary's Square), the home of the Jervers sisters was acquired by Richard Cooper in order to safeguard its use as a Methodist Meeting Place. In 1811 the house was demolished and replaced by a Methodist Chapel, and remained in this use until 1878.

|

|

1784

|

In 1988 the Suffolk Records Society published the diary of Francois de La Rochefoucauld under the title "A Frenchman's Year In Suffolk, 1784." It is packed with detailed observations of life in English country society at the period.

Dr Francis Young has pointed out the following note from this visit, to illustrate local tolerance to Catholicism:

"The reminiscences of the French aristocrat François de la Rochefoucauld, who visited Bury with his brother in 1784, are also very revealing -

everyone knew what was going on when the Catholics went to mass, François recalled, but no one did or said anything because everyone got along so well. It is possible that some of the Protestant gentry may have shared in François’ own fashionable Enlightenment indifference to

matters of religion. "

|

|

Gravestone of Mary Haselton

|

|

1786

|

During this year came an incident which had a big impression on local people. This was the tragic death of a nine year old girl, while saying her prayers. Mary Haselton was struck by lightning while at Vespers, an event which seemed to question the faith of the religious people of the time. Her gravestone can be seen today attached to the Mausoleum in the Great Churchyard at Bury St Edmunds.

Dr Francis Young has pointed out that her memorial is surmounted by the letters IHS within a sunburst, which is a Jesuit symbol, and refers to her parents as 'Roman Catholics', rather than the less respectful word, 'Papists'. "The very fact that the Roman Catholic religion could be

mentioned explicitly and respectfully on a public monument was a huge breakthrough," he has written.

|

|

1789

|

A new law was passed which allowed Roman Catholics to worship openly. A license was given to the Westgate Street chapel for this purpose in 1791, but it seems that public worship had been quietly going on here for many years already.

At Bury St Edmunds, the Jesuit priest, John Gage died. He had built the catholic chapel in Westgate Street and run the illicit Catholic mission to Bury since 1755. Francis Young has noted, "Ironically, the Jesuit order did not officially exist between 1773 and 1814, but this had made little difference to Gage’s mission. When he died, the manor in Westley which his mother had given him reverted to the Jesuit Province, and would eventually fund the building of St

Edmund’s Church in 1836. Gage was succeeded by an American priest, Charles Thompson."

|

|

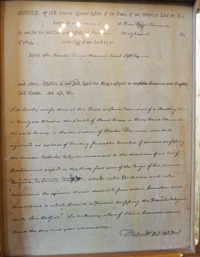

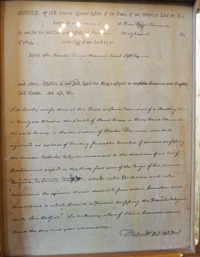

License authorising Catholic worship 1791

|

|

1791

|

In 1791 the Catholic chapel in Westgate Street, built by John Gage, was the first in England to be officially licensed for worship under the Second Catholic Relief Act of 1791. The license was issued at the Quarter Sessions on 18th July, 1791, before the Justices Sir Charles Davers, baronet and Capel Lofft esq, "and others". It was for part of a the lower rooms of a dwelling house in Westgate Street, occupied by Charles Thompson. Charles Thompson SJ was the first parish priest following John Gage and took over in 1790.

Wikipedia states, "The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791 is an Act of the Parliament passed in 31 George III. c. 32 (1791) relieving Roman Catholics of certain political, educational, and economic disabilities. It admitted Catholics to the practice of law, permitted the exercise of their religion, and the existence of their schools. On the other hand, chapels, schools, officiating priests and teachers were to be registered, assemblies with locked doors, as well as steeples and bells to chapels, were forbidden; priests were not to wear their robes or to hold service in the open air; children of Protestants were not to be admitted to the schools; monastic orders and endowments of schools and colleges were prohibited."

|

|

Catholic chapel on Warren's map 1791

|

|

blank |

Gage was a Jesuit who had built the chapel in 1761, and led his technically illegal Catholic Mission to Bury St Edmunds from there. Warren's map of 1791 was the first map to show the location and lands of the Catholic Chapel. This chapel would be the only centre for Catholic worship in Bury until the modern church was built in 1837.

Dr Francis Young has noted that, "Elizabeth Inchbald brought Bury’s tolerance of Catholicism to the attention of the nation in 1791, when she published a two-volume novel entitled "A Simple Story. " In the story, "Mr Dorriforth, (is) a Jesuit who ends up being dispensed from his vows when he inherits an earldom – Inchbald based this part of the story on Sir George Mannock of Gifford’s Hall, who was killed in a coach accident in 1783 on his way to obtain a dispensation from Rome from his Jesuit vows."

"Another key character in the story is Mr Sandford, a severe Jesuit whom Inchbald based on her own childhood tutor at Coldham Hall, James Dennett."

Inchbald was born "Elizabeth Simpson, the daughter of a Stanningfield farmer, and received an education at Coldham Hall that allowed her to become an actress in London. As Elizabeth Inchbald she achieved fame as the greatest English woman dramatist of the eighteenth century. "

|

|

1799

|

Non Conformity was now well established in the villages as well as the town. In August 1799 the newly built Meeting House at Tan Office Green at Chevington was set aside for worship. Chevington became the local centre for Independency serving the villages of Chedburgh, Rede, Hargrave, Ousden, Lidgate, and even Wickhambrook. This chapel became leased to Primitive Methodists in 1844.

|

|

Baptist cemetery today

Baptist cemetery today

|

|

1800

|

The Baptist Church was established by 12 people in Bury in 1800, but at the time the congregation would have called the building the Ebenezer Chapel. It was located on Lower Baxter Street and Looms Lane. Membership grew to 49 over the first 23 years of the church’s existence under the leadership of four successive pastors. This chapel was enlarged in 1828, and it would be used until 1834, when a new church was built in Garland Street.

Part of the cemetery attached to the original Baptist church of 1800 can still be seen in the Lower Baxter Street public Carpark.

|

|

St Botolphs Chapel

|

|

1801

|

In about 1801 St Botolph's Chapel, by this time in the yard of the White Hart public house, was still standing. The White Hart was in Southgate Street, and is a guest house in 2005. In his History of Bury St Edmunds published in 1804, page 221, Edmund Gillingwater recorded that "this building was standing about three years since, but is now (1804) wholly taken down and demolished".

In 1801 the Presbyterian Minister, Nathaniel Phillips, persuaded some of his congregation to embrace the rationalist doctrines of Unitarianism. Many of his flock then left to join the Congregational Church, but today we still know the building in Churchgate Street, Bury, as the Unitarian Meeting House.

|

|

1802

|

In 1802, Benjamin Greene joined the Congregationalist Chapel in Whiting Street. He paid a subscription to reserve a pew for himself and family, and this is the first written evidence of the would-be brewer's presence in Bury.

|

|

1804

|

The Congregational Church in Whiting Street was re-built in 1804, although the congregation could be dated back to the 17th century.

|

|

4A St Marys Square |

|

1811

|

A Wesleyan Chapel was built in St Mary's Square on a site of a house in which John Wesley had often preached. Between 1755 and 1790, he had preached in St Mary's Square on 17 occasions. The house was the home at the time of the Jervers sisters. In 1780 it had been bought by Richard Cooper, a local Methodist, to safeguard it as a home for the Jervers sisters and as a Methodist Meeting House. By 1811, the Jervis sisters had died, and the house could be demolished to make way for the new chapel. It survived in this use until 1878 when it was sold for use as a house once again. Today it is number 4A, St Mary's Square, a private house.

|

|

1819

|

The poverty and ignorance amongst the working people led to movements such as the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge. In Suffolk the Suffolk Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church was in action to provide elementary and bible schooling. They set up Central Schools, such as the National School in Field Lane. This road is today called Kings Road, and the location was opposite the offices of the Bury Free Press.

|

|

1820

|

The followers of John Wesley had experienced some disagreements and by 1811 a splinter group in Staffordshire began to build their own chapels and called themselves Primitive Methodists. Although White's Directory of Suffolk of 1844 recorded that a Primitive Methodist Chapel was built in Garland Street, Bury St Edmunds, in 1820, this did not actually occur until 1830. Probably this was a simple misprint.

|

|

View of St Nicholas 1821

View of St Nicholas 1821 |

|

1821

|

This view of St Nicholas's Chapel in Eastgate Street was engraved and published in 1821, (copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum), described as "View of a ruined chapel with a Gothic window in Bury St Edmund's. 1821 Etching". The print was made by Jacob George Strutt, and sold at Deck's shop on Angel Hill, Bury St Edmunds. It was one of a series entitled "Bury St Edmund's Illustrated in Twelve Etchings". It shows that the window removed from St Petronilla's demolished hospital at Southgate Green was in place at the junction of Hollow Road and Eastgate Street by 1821.

|

|

1823

|

By 1823 there was a Baptist chapel, called the Ebenezer Chapel, in Lower Baxter Street, founded in 1800. In 1823 its new pastor was Cornelius Elven, a convert from Congregationalism. Elven had a strong personal following, and he did not restrict his ministry to Bury St Edmunds.

He seems to have been willing to travel wherever he was invited and he would preach in the open air using a farm wagon as a pulpit. His diary states at times he preached to a congregation of 3000 people at Glemsford. He also carried out baptisms in a specially dug pool by the River Glem at Scotchford Bridge at which he claims there were never less than 20 candidates, some almost 80 years of age. Many of the Glemsford congregation would regularly travel to Bury to worship with Elvin in the Lower Baxter Street chapel. By 1829 about forty of these Glemsford worshippers would start building their own chapel at Glemsford.

|

|

1826

|

Catholic emancipation was one of the major issues in the 1826 General Election. The corporation of Bury opposed emancipation, despite the fact that both the Earl of Euston and Lord Hervey supported the cause. This led to some uncomfortable moments for both sides as the corporation more or less had to return both men as MP's because of their control of patronage in the town. There was pressure from reformers from all sides, and the corporation was no longer leading opinion as it once had. It was extraordinary that 37 mainly Tory men could still elect a Whig in this way.

|

|

Independent Congregational Chapel |

|

1828

|

In 1828 the Independent Chapel was opened in Northgate Street, Bury St Edmunds, at the Angel Hill end. In 1866 it was almost rebuilt, and comfortably benched, containing 400 sittings. The building still exists today on the corner of Looms Lane and has had a variety of secular uses as well as the religious.

From 1828 to 1839 there was also a great expansion in non-conformist activity in Haverhill. In 1828 the Baptists opened a new meeting house, to be followed by the Quakers house in 1834, the Methodists in 1836, the old Independents and the Market Hill Chapel in 1839.

|

|

1829

|

In 1829 some 44 members of the Baptist Church in Looms Lane, Bury St Edmunds asked to be released from that congregation in order to start up their own chapel at Glemsford. These were people from Glemsford and surrounds who had been travelling the dozen miles to Bury each week to worship under Cornelius Elvin.

The new Ebenezer Chapel at Glemsford was opened by Pastor Elvin in 1830 with a large congregation and the first resident minister appointed was Pastor Robert Barnes who ministered there for 27 years. Membership included Baptist leaning worshippers from Sible Hedingham, Clare and all the surrounding villages. A plaque over the door read, "Strict Baptists", and the congregation seems to have required strict rules of conduct for its members.

|

|

No. 15a Garland Street |

|

1830

|

The followers of John Wesley had experienced some disagreements following Wesley's death. His church became increasingly centralised, authoritarian and "Churchy". After 1811 two preachers from Stoke on Trent began to hold outdoor camp meetings for worship, which were very popular, but judged to be "highly Improper" by the Wesleyan Methodist Conference. These new preachers wanted to return to the fervour and evangelistic spirit of Methodism as it was in its primitive beginnings. In 1811 the first Primitive Methodist chapel was erected in Tunstall in Staffordshire, and admitted women to be preachers and office holders. It attracted the humblest members of the community.

By 1821 the Primitive Methodist movement reached East Anglia, and by 1829 two such preachers from Brandon came on a mission to Bury St Edmunds. They were so successful that a house in Garland Street was quickly purchased and converted into a chapel.

Primitive Methodist services began in Garland Street in Bury St Edmunds on January 22nd, 1830. This chapel is now a private home, number 15A Garland Street. Meanwhile, in Bury, the old Wesleyan Methodists continued to attend chapel in St Mary's Square.

|

|

Deanery Tower in Hadleigh |

|

1833

|

The Oxford movement in the Church of England advocated reviving certain Roman Catholic doctrines and rituals, and began with a conference in Hadleigh, Suffolk held at the Deanery. The Hadleigh Conference met in late July 1833 at Hadleigh , where Hugh James Rose was Rector. The conference held in the Deanery Tower led to agreement over the principles of the new movement: to proclaim the doctrine of the apostolic succession; the belief that it was sinful to give the laity a say in church affairs the need to make the Church more popular and, to protest against any attempts to disestablish the Anglican Church.

This attempt to stir the Established Church into new life arose among a group of spiritual leaders in Oriel College, Oxford. Prominent among them were John Henry Newman, John Keble, Richard Hurrell Froude, Charles Marriott, Edward Bouverie Pusey and Richard William Church. The Oxford movement has exerted a great influence, doctrinally, spiritually, and liturgically not only on the Church of England but also throughout the Anglican Communion.

|

|

New Baptist Chapel

|

|

1834

|

In 1834 the new Baptist Chapel was opened in Garland Street, replacing the 1800 one in Looms Lane and Lower Baxter Street, although the old churchyard can still be seen today at the foot of the Borough Offices car park. It was built by the firm of Steggles and can seat nearly 1,000 people. The Pastor, Cornelius Elvin, was responsible for the large increase in the congregation since he took over in 1823. This chapel is still in use today.

In Haverhill the old Quaker Meeting House had been in bad disrepair and by 1834, a new meeting house was finished in Quakers Lane, on the same land they had held since 1674.

|

|

Commission Report on Bury St Edmunds

|

|

1835

|

In 1835 the Commission into the Municipal Corporations in England and Wales published their Report. Each Borough had an individual section in the report, and the Report on the Borough of Bury St Edmunds was signed by George Long and John Buckle. The reports in general were scathing about the conduct of affairs in the Municipal Corporations, and that on Bury was no different.

The rivalries on the council frequently caused divisions and contests on elections, and a successful candidate was then expected to pledge his vote and support to whoever introduced him to office.

The report noted a bias in favour of churchmen, as no dissenters had been elected. Nobody had been excluded for political reasons at Bury, but the Report said that "a bias exists in favour of persons whose political opinions coincide with those of the majority."

The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 introduced the first elements of democracy into local government in Bury St Edmunds and the rest of England and Wales.

|

|

1836

|

Between 1833 and 1848 the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge published a series of articles on Historic Towns in 'The Penny Magazine'. An article in 1836 on Bury St Edmunds gave a snapshot of the town at the time, including the following;-

Bury also possesses three charity-schools, in one of which forty boys, and in another fifty girls are instructed and clothed. They are supported partly by subscription and partly by an endowment of £70 per annum ; as well as two Lancasterian schools, one for boys, the other for girls, established in 1811.

Joseph Lancaster, a Quaker, published an account of his educational work in 1803 called "Improvements in education as it respects the industrial classes of the community".

Joseph Lancaster had found that at his 'Lancasterian School' in Southwark one 'teacher' could teach say five boys one item of knowledge in reading, writing or arithmetic. These five boys would teach another five. These would teach five more. He also adopted use of the slate and slate pencil to replace costly pen, ink and paper. In this way education could be provided very economically, and each boy paid 1p per week.

Financial difficulties led in 1808 to the schools being taken over by a non-conformist group who formed the Society for Promoting the Royal British or Lancasterian System for the Education of the Poor ( renamed in 1814 as the British and Foreign School Society or BFSS).

In 1836 the Tithe Commutation Act was passed which ended the practice of delivering one tenth of all agricultural produce to the titheowner, who was often the local parson. In many ways the new Tithe Rentcharge was a worse burden on farmers as they had to find the rental payment whatever the state of the harvest, or the effort of the farmer. What was worse was that with an increasing number of religious denominations, they could not accept that the fruits of their labours should go only to the Church of England parson.

|

|

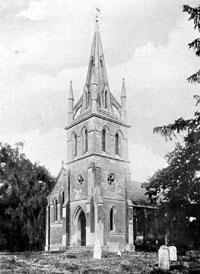

Westley Church

|

|

blank |

At Westley the new parish church of St Mary's was completed after a two year building project. The old church of St Thomas a Becket was apparently beyond repair. It had suffered severe storm damage in the 18th century, and had been in a long slow decline ever since. The new church was built on a more prominent site. It was unique at the time for a Church of England building in that it was built of concrete, with a cast iron roof, and was part funded by the Marquess of Bristol. He gave the land and £600 towards the £1,400 bill. It was built with a spire above the tower, which could be seen from Ickworth House. This spire was removed in 1961.

The architect and builder who constructed the new church was William Ranger of Brighton. He had patented a form of concrete known as Ranger's Artificial Stone in 1832, and by 1834 he was using it to produce pre-formed blocks. Both his blocks and liquid concrete were used at Westley. The roof was clad with slate, but supported by cast-iron hammer beam trusses, which was another new feature for the time.

|

|

Existing catholic chapel

|

|

blank |

Meanwhile there was some disquiet expressed in the local press because the Roman Catholic congregation in Bury St Edmunds were planning to build a new church. Catholic worship had been made legal in 1791, and the tiny chapel in Westgate Street was bursting at the seams. The Bury and Norwich Post and Suffolk Herald 6 April 1836 referred to the external construction and funding of the new Church. It also highlighted the disquiet around that time from opponents of the Faith:

"We believe that the expense of this edifice is defrayed from the general fund for the creation of Catholic Chapels upon which every town has a claim in its turn. This fact may serve to quiet the alarms of some of those persons who see in every announcement of a new Catholic place of worship the approach to the restoration of ‘Popish’ supremacy in this Country........."

The paper goes on to attempt to alleviate its readers fears as follows:

"Supposing that there be 510 R C Chapels, each having a congregation of 300 persons on the average, the total will not amount to a hundredth part of the population, notwithstanding the constant immigration of Irish poor. These fears of the spread of Popery, and the perpetual hankerings after the interposition of the secular arm, are wretched complements to the Protestant Church with its endowed Ministers posted in every parish."

|

|

Rehoboth Chapel Westgate Street

|

|

1837

|

Queen Victoria was to be the last of the House of Hanover, but she ruled for 64 years over an era of unprecedented expansion.

Following a dispute with their pastor, Cornelius Elven, about 30 members of the Baptist Church left and set up their own Rehoboth Congregation. They set about creating their own chapel in Westgate Street, which was ready for worship by 1840. Elven was brought up a Congregationalist but had joined the Ebenezer Baptist congregation following his own bible studies. He became their Pastor in 1823, and was responsible for gaining a great number of new worshippers, to the extent of needing to move to a new chapel in Garland Street. He was a liberal Baptist, and the breakaway group desired a stricter form of worship.

Around this time, in the 1830's, several of the dissenting groups reformed new congregations. A few years earlier some Congregationalists left to set up the Chapel at the bottom of Northgate Street.

|

|

Roman Catholic Church

|

|

1838

|

During 1836 and 1837 the Roman Catholic Church of St Edmund was built in Westgate Street in Bury, to replace the overcrowded chapel adjacent. It was built in the Greek revival style, and dedicated on 14th December, 1837.

|

|

1839

|

In 1836 the congregation of Haverhill's Independent Congregational Church had a disagreement over finances and a group split away to found the Market Hill Chapel where Chapmans is today. The Market chapel was finished in 1839 by the new group. The original group became known as the Old Independents and also built a new meeting house at this time.

|

|

Rehoboth Baptist Chapel

|

|

1840

|

In Bury St Edmunds a second Strict Baptist meeting place was opened at the Rehoboth Chapel in Out Westgate Street. The name Rehoboth was derived from the Bible. In the 26th chapter of Genesis there is a well of water named “Rehoboth” and an explanation as to its meaning. “And he moved from there and dug another well, and they did not quarrel over it. So he called its name Rehoboth, because he said, 'For now the Lord has made room for us, and we shall be fruitful in the land'”. This break-away congregation desired a stricter form of Baptist worship than that preached by the more liberal teachings of Cornelius Elven at the Baptist Chapel in Garland Street.

Meanwhile Methodism was a rising force in some places. Primitive Methodists of the Wickhambrook and Newmarket Circuit had leased the Independent Chapel at Chevington from the Bury Congregationalists by 1840. This arrangement continued throughout the century, and Chevington was regarded as a local centre of nonconformity, along with Wickhambrook.

|

|

St John's Church c 1866

|

|

1841

|

In 1841, built of white bricks produced at nearby Woolpit, and endowed by the Marquis of Bristol, a dramatic new church was being built in Long Brackland. It was to be dedicated to St John the Evangelist and the architect was William Ranger of Brighton who invented an artificial stone known as ‘Ranger’s Artificial Stone’, patented in 1832. William Ranger had recently completed work on the new Westley church, St Mary's, of 1835 /1836 which was built mainly with his new artificial stone or concrete.

The builder of St John's Church was Messrs Bell and Sons of Cambridge and the church was dedicated on October 21st 1841. This picture is from about 1866 but even by that date there was no Orchard Street yet built, and very few other buildings around the church.

|

|

St Johns Church in 2005

|

|

1842

|

In Bury, St John's Church was consecrated. With its distinctive spire of 178 feet, it was built to serve the expanding Victorian town towards the north. In the spirit of the industrial age, its interior columns were made of cast iron, supporting a brick built structure. It was built through 1841 and cost £6,000, all raised by public subscription. The first Vicar of the church was the Rev.B. Rashdall.

Much of the old Long Brackland was re-named St John's Street. The name Long Brackland survives today only at the bottom end of its former length. St John's was the third Anglican church in the town, but St John's parish was not established until 1846.

|

|

1844

|

St Mary's church in Bury was completely restored at a cost of £5,000 to £6,000. Wilkin's Bury Guide of 1867 reported that it now had 2,000 sittings of which 500 were free.

An Order in Council finally removed the right to control the clergy of St James and St Mary's from the town corporation. These two churches and their parishes were finally made part of the Thingoe Deanery and the Arch Deaconry of Sudbury, under the Diocesan control. The corporation had inherited the Abbot's old freedom from episcopal control when they got their third charter in 1614, and finally this freedom was removed.

|

|

First train to Bury |

|

1846

|

In December, 1846 the long hoped for railway line arrived at Bury St Edmunds from Ipswich.

|

|

1847

|

At Chevington a new school was built by the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church. Such schools were known as National Schools.

|

|

1848

|

By 1848 the Primitive Methodists had established a presence in seventeen villages around Bury St Edmunds. The old Wesleyan congregation declined slightly as members defected to the Primitive Methodists.

|

|

Chapel House, 23a Garland Street |

|

1851

|

After twenty years at 15A Garland Street the Primitive Methodist congregation had grown considerably and they needed to find new premises. This would be a purpose built chapel, rather than be a converted house as at 15A.

In 1851 the primitive Methodists completed their new chapel in Garland Street, located at what is today number 23A Garland Street. This had a capacity of 120 people, and would be in use until 1902.

Their previous chapel, located nearby, at number 15A Garland Street, would be sold to the Plymouth Brethren in 1853.

In 1851 there was a national census of religious worship to measure how many places were available in church and chapel to accomodate the growing population. Census Day was 31st March, 1851. For some reason the Primitive Methodists at Garland Street did not submit a return. Perhaps the change of location caused it to be overlooked.

The St Mary's Square Wesleyans reported attendances well below their capacity of 400 places. Both the Baptists in Garland Street and the Whiting Street and Northgate Street Independent chapels reported congregations larger than the Wesleyans. The Quakers had declined over the last fifty years and reported a very small number attending. The Unitarians in Churchgate Street reported numbers similar to the Wesleyans.

This upsurge in independent religious activity has been seen as very important in ameliorating the economic and political disturbances of the times. In 1848, the year of revolutions throughout Europe, it was able to be thought that "Methodism saved us from a bloody revolution", although it is clear that it was Primitive Methodism that captured popular support.

|

|

15a Garland Street |

|

1853

|

In 1853 the Plymouth Brethren took over the old Primitive Methodist Chapel at 15A Garland Street, and would use it for worship until 1939. The Primitive Methodists had already moved to 23A Garland Street into bigger premises two years earlier.

|

|

1854

|

The existing railway link from Cambridge to Newmarket was extended to Bury St Edmunds which was already linked by rail to Ipswich and beyond. At Bury's Northgate Station further works had to be carried out to accommodate a new line from the west.

In the 1850s there was a considerable movement against burial of the dead within town or city limits on health and hygiene grounds. Burial Acts of 1852, 1853 and 1854 gave the crown the right to issue Orders in Council to close specific burial grounds throughout the country.

On 11th August, 1854, such an Order in Council was made instructing that with effect from 21st August, 1854, there should be no more burials within inhabited areas. However the Order included a few exceptions to that general rule, at Diss, Manchester and at Bury St Edmunds.

The appropriate Order in Council for Bury St Edmunds read as follows:

"BURY ST. EDMUNDS.—Burials to be discontinued

in the churches of St. Mary and of St. James,

(reserving to Mrs. Harriet Haggitt the right

of interment in her husband's vault under

the chancel of St. James's Church) ; and

from and after the first of January, one

thousand eight hundred and fifty-five, in the

churchyards of the same, in the burial-ground

of the Whiting-street Chapel, and in the

Baptist Burial-ground. To be discontinued

forthwith in the Friends' Burial-ground

within five yards of the walls of the chapel

and of any dwelling-houses.

C. C. Greville."

|

|

1855

|

at Bury St Edmunds the deadline of January 1st could not be met and extension of time was granted, but only for a few months. The land for the new cemetery was purchased by Bury St Edmunds corporation from Mr George Brown of Tostock Place. It cost £2,276.16.0, and was known as the Westfield Farm purchase. The first plot of land laid out was about 11 acres. Up to this time the road up to the new cemetery had been known as Field Lane, but it naturally now became called Cemetery Road. At that time the land was on the edge of town. Further development came along Cemetery Road and in 1911 it would be renamed Kings Road.

The chapels and the lodge at the Cemetery were designed by Cooper and Peck, and together with the entrance gates cost nearly £1,900.0.0. Laying out the ground and accomodation works cost another £5,500. The new cemetery was finally opened for burials on October 1st, 1855 and the chapels were consecrated by the Bishop of Ely on 23rd October of that year. A further plot of land would need to be bought in 1880 to enlarge the burial ground.

The Churchyard between St Mary's and St James' was now closed to further burials. It had been used for burials at least since 1148 when it was enclosed by the abbey precinct walls. The earliest surviving gravestone today is dated 1637, and many gravestones have been removed and lost over the years.

|

|

1857

|

At around this time many villages without a Chapel began to hold open air "Camp Meetings" on Sundays. These would be addressed by a local preacher who could be expected to walk 8 or 12 miles in all weathers to take the camp meeting. Most of these preachers were local working people. Shopkeeper, farm horseman, and fishmonger were the weekday jobs of three local preachers. Some camp meetings survived into the 1920s.

|

|

St Peters Church

|

|

1858

|

St Peter's Church was dedicated in Hospital Road, Bury. It was to serve the growing population in Westgate Ward, and was set up as a chapel-of-ease for St Mary's. It was started in 1856, largely supported by three generous ladies and the site donated by the Marquess of Bristol.

In 1858 the Ebenezer Baptist Chapel at Egremont Street, Glemsford combined with Clare to pay the cost of opening a meeting room at Cavendish. However, a rift among the Glemsford Ebenezer members was now becoming evident. Despite this, the Ebenezer Chapel at Glemsford would survive until 1986.

|

|

1859

|

Charles Darwin published his revolutionary book on “On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life”. The contents of this book caused a national furore.

The non-conformist road was not always a smooth one.

Some members of the Glemsford Baptist congregation claimed the Ebenezer chapel was too “hyper-Calvinistic” and wanted a more “Evangelistic view”. This discussion rumbled on for a year, but such were the convictions on both sides that 32 members left the Ebenezer congregation and built their own chapel, called Providence Baptist Chapel, on Hunts Hill at Glemsford. This opened on December 11th 1859.

|

|

1860

|

At Thurston, St Peter's church tower collapsed, quickly followed by the nave in March 1860. A collection raised £3,500 to rebuild it, and the new church re-opened in October, 1861.

|

|

Primitive Methodist Chapel extension

|

|

1865

|

In 1865 the congregation of Primitive Methodists had continued to expand. The Chapel at 23A Garland Street had been built with a capacity of 120 places, and this was too small by this time.

An extension was built to number 23A in 1865 which brought the seating capacity up to 160 worshippers. The event was commemorated by the plaque shown here, which was photographed by Martyn Taylor. It is slightly unclear, but the inscription reads, "This stone was laid Oct 9 1865 by W Chapman of Barnardiston. M Warnes, T Woodall Ministers."

This chapel would be in use until 1902, when the Primitive Methodists would move to 4 Northgate Street, a former Congregational Chapel.

|

|

Whiting Street Church

|

|

1866

|

The Independent or Congregational Church in Whiting Street was re-fronted, and internally improved. Since 1972 it is called the United Reformed Church.

Externally, the Victorian gothic facade that we still see today was added in 1866. Meantime, in 1851, the Sunday School which had met for 50 years needed new premises so the school-room was built and a further extension with smaller rooms was added in 1887.

(The memorial seen in the front of the church dates to 1904.)

|

|

1867

|

During 1867 the Bury firm of Wilkin and Son, of 2 Angel Lane and 16 Guildhall Street, published their "Guide to the town and Antiquities of Bury St Edmunds, with a classified list of Trades and Professions." It noted that St Mary's church organ, built by Gray's of London at a cost of £1,000 had just been removed for a rebuild. The tower had a "capital peal of eight bells". The "high, square unsightly pews" are to be replaced by graceful benches, wrote Wilkin, who also advocated removal of two "large ugly galleries". The living of St Mary's was reported to be a perpetual curacy, in the patronage of John Fitzgerald, esq, endowed with £240 a year. A vicarage house had just been purchased by public subscription for the incumbent, Reverend John Richardson, MA.

At St James's church, nearby, Lot Jackaman the Bury builder, was continuing a long renovation process, started in 1864. Wilkin noted with approval that the galleries there were wiped out in 1863-64, and the "high stiff-looking pews have been superceded by oak benches", giving about 2,000 sittings, of which 400 are free. "Mr F Fearnside, a skilful musician, is the organist, and has succeeded in forming a most excellent choir". The living is a perpetual curacy and the incumbent is Rev Frank Chapman.

Similarly, St Marys Church at Haverhill was being enthusiastically "restored", so that only its tower remains as clearly medieval today.

|

|

The Green at Barrow

The Green at Barrow

|

|

1869

|

At Barrow a Primitive Methodist Chapel was built with a tower. The chapel was later taken over by the Salvation Army, but the building became redundant. The buildings were demolished, but the tower was kept because it housed a public clock. Today, only the tower survives, with no clock. as a curious relic standing over the Green.

|

|

1870

|

At St John's church change was afoot. In the words of Simon Knott, in his exemplary website "Suffolk Churches.co.uk":- "It was not until 1870 that the first Vicar of the church, the Rev. B. Rashdall, was replaced by a young and enthusiastic Anglo-catholic priest, Father Stewart Holland. The effect was somewhat akin to a whirlwind descending on the church. During the seven years of his incumbency, the church was completely transformed, to emerge as St John the Evangelist, the county's flagship Anglo-catholic shrine."

" In 1871 and 1872, the great pulpit was taken down, and replaced by a simple reading desk. The church was decorated for Easter and Christmas. The black gown was given up, and surplices were worn by priest and servers. Holy Communion was introduced on every Sunday, and pew rents were abolished. Services were introduced on weekdays, and some of them were sung.

In 1873, choral Mass was introduced; the choir was surpliced, and a vestry built."

|

|

Repairs to St John's church |

|

1871

|

In 1871 the Spire of St Johns Church in Bury St Edmunds was struck by lightning. The spire had to be shrouded in scaffolding to make repairs. The lightning strike gave local photographers the opportunity to take birds eye view photographs of the views from the spire.

|

|

The Fennell Homes

|

|

1874

|

A local Quaker, Sarah Fennell left money to another Friend, Sarah Ann Bott. She decided to use the money to build four flats on land sold to her by the Society of Friends. The Fennell Homes, as they were called, were for respectable women in reduced circumstances, who were willing to read the bible to the poor of Bury, and engage in other home mission work. The Quaker Cottages can still be seen in St Andrews Street, still occupied by retired women Quakers. The Friends Meeting House is the white building behind the Fennell Homes.

In Haverhill the Methodist Chapel was built in Camps Road. It replaced a series of temporary homes used by the Methodists of Haverhill since they were founded in 1857. The current building on the same site was built in 1970.

|

|

Catholic Sanctuary Lamp |

|

1876

|

The Roman Catholic church in Westgate Street, Bury St Edmunds, received its sanctuary lamp in 1876. It had a red light indicating the presence of the Blessed Sacrament and was one of the early gifts to the Church, donated by Irish drovers who took cattle across Europe during the mid-19th century. They saw that the Church did not have a proper sanctuary lamp and provided one made of brass bearing the inscription ‘Hibernae Donum Sancto Edmundo AD MDCCCLXXVI’ confirming the date of this ‘Gift from Ireland’ as 1876.

It would appear that the Irish were mainly immigrants to England who worked as drovers in this country ‘driving’ cattle between markets and to the ports for export to Europe. One of the markets involved was Bury St Edmunds, and the drovers would attend Mass at Westgate Street on a Sunday, between jobs, usually standing in a group at the back of the church.

|

|

The Wesleyan Chapel

|

|

1878

|

The Wesleyan Chapel was built in Brentgovel Street, to replace the earlier chapel in St Mary's Square. The chapel in St Mary's square had been built in 1811, and in 1878 was sold as a house, today called 4A St Mary's Square. The Brentgovel Street Methodist Church is still in use today, although it has been altered and extended from its appearance in 1878.

|

|

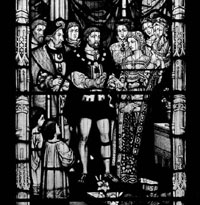

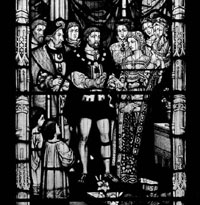

The Queen's Window

|

|

1881

|

This stained glass window was given to St Mary's church in 1881 by Queen Victoria. It portrays the life of Mary Tudor, whose funeral was the last of the great ceremonies performed at the Abbey. After she was widowed she married Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. Her body was re-interred in St Mary's Church on the orders of King Henry VIII. This photograph from the time, comes from the Spanton-Jarman Collection at Bury St Edmunds Record Office. It was printed from a glass negative approximately 164mm x 214mm.

Queen Victoria herself did not attend the installation of the window. She had not been seen in public since the death of her husband, Prince Albert, in 1861. It was a great weakness of her reign that she kept in seclusion until 1887, an extreme act of mourning lasting for 25 years.

|

|

1884

|

The Old Independent Congregational Church was started in Haverhill for non-conformist worship and could seat nearly 800 people. At this date it was in Essex, as the County boundary ran down the Colne Valley Road.

|

|

Salvation Army Badge

|

|

1887

|

The Salvation Army came to Bury in March 1887, and two sisters, Captain and Liutenant Newton

set up its barracks, as it was called, on the corner of Honey Hill and Sparhawk Street. Within three years they would move to a brand new building in St Johns Street.

|

|

Congregational Sunday School |

|

blank |

In August 1887 the Congregational Church Sunday School had a fine new building erected for it. Located next to the Congregational Church in Whiting Street, it was opened by Edward Greene, MP, and his wife, the Lady Dorothea Hoste. Today this building is known as the United Reformed Church Annexe. It was built by Frederick Tooke, a builder of 76 Mill Road in Bury. Greene was a member of the Greene King brewing dynasty, and lived at Nether Hall in Pakenham. In 1836 he had bought Greene's Brewery from his father, and had just become Greene King's Chairman when it amalgamated with King's Brewery in June, 1887. Since Benjamin Greene's arrival in Bury in the 1790's the Greene family had attended the Congregational Church. Lady Dorothea had her title from her first husband, Sir William Hoste, Admiral of the Fleet, who died in 1868. After marrying Greene in 1870, she retained her title of Lady Hoste.

|

|

1889

|

The Salvation Army Barracks was started in St John's Street in Bury. Land was bought at the bottom of the street, and the building project began. The Salvation Army came to Bury in March 1887, and set up its barracks, as it was called, on the corner of Honey Hill and Sparhawk Street. The two sisters Captain and Liutenant Newton soon raised the army to a size where a move was needed. On October 10th 1889 the first foundation stone was laid, and the building opened in the Spring of 1890.

|

|

Salvation Army Citadel

|

|

1890

|

On March 21st 1890, the Salvation Army's new Citadel was opened at the bottom of St Johns Street in Bury St Edmunds. The building had cost £1,000. The Salvation Army was set up in London in 1878 by William Booth with the motto "Through Blood and Fire", epitomising his military and disciplined approach to Christianity.

|

|

1891

|

Haverhill's West End Congregational Church was built on Withersfield Road to house the growing Sunday School and congregation of the Market Hill Chapel. It could hold about 450 people. Market Hill chapel became Chapman's shop in the late 20th century.

|

|

Baptist Sunday School |

|

1892

|

The Baptist Church in Garland Street had run a Sunday School since 1824. A fine building was erected opposite the Baptist Church to house the Sunday School. A memorial plaque was laid by James Stiff, who now lived in London, but who had once attended the Sunday School.

|

|

1895

|

The Railway Mission was a charity founded in 1881 to bring the Gospel to people working on the railways. The railways employed thousands of men who often had to work during normal church hours. In 1895, local railwaymen approached Mrs Arthur Ridley, about starting a local branch of the railway mission in Bury St Edmunds. Mrs Ridley was a widow, and a Congregationalist from the Northgate Street Chapel, and she began by leading services at the station. A committee was formed, called the Mission Band, and the Station Master, a Mr Cook, made premises available to them. Mrs Ridley was made the local Superintendent of the Mission.

From 1895 until 1900, a room in the Station Master's house by the Northgate railway station in Bury St Edmunds would be used as the mission to railwaymen who worked on the Bury line. Soon the services attracted the workers' wives and children, and activities were organised for them.

By 1900 the number grew so much that the Railway Mission Hall was built on Fornham Road, just past the railway bridge.

|

|

Lathbury Institute |

|

1896

|

In Bury, the Lathbury Institute was built near St Johns Church, and was used as a Mission Room for that parish. This church hall stands in Church Row and cost £400 to build, the money coming from a bequest left by Elizabeth Lathbury. The Lathbury family lived at 2, Angel Hill. Soon after this picture was taken the premises were converted to private dwellings.

At Walsham le Willows, the Church of England Society for the Housing of waifs and strays acquired Walsham Hall. It housed 40 children for some years. Today this charity is called The Childrens Society.

|

|

1897

|

At St Mary's church, Haverhill, the vestry and organ chamber on the north of the chancel were built, and the arches of the Lady Chapel reopened.

|

|

|

Quick links on this page

Top of Page 1700

Friends Meeting House 1750

Catholic Chapel 1760

Catholic Relief Act 1791

Ebenezer Chapel 1800

Primitive Methodists 1820

Oxford Movement 1833

Catholic & Rehoboth 1838

Plymouth Brethren 1853

Wesleyan Chapel 1878

Salvation Army 1890

|

|

Next Section

|

In the 20th century there was a long slow decline in church attendances. The two world wars caused many to question their faith.

|

Prepared for the St Edmundsbury Local History Project

by David Addy, July 17th, 2020

|