|

|

|

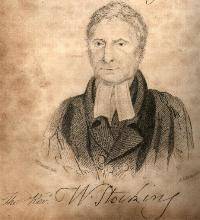

After his arrest Corder was taken to Polstead. A hearing there remanded him to the county gaol in Bury St Edmunds to await trial. On the Sunday before the trial, the prison Chaplain, Reverend Stocking, gave a sermon on the theme "Thou shalt not kill". The point was not lost on Corder.

The Assizes were held at Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds during August 1828. Corder's trial was scheduled for Monday 4th. Even as early as July 21st, the "Times" reported "so great is the anxiety to be present at his trial, the lodging-house and hotel-keepers in Bury are already speaking of an increase in their usual assize prices." Because of the notoriety of the case, immense crowds gathered and the hearing was put off until Thursday 7th. It was announced on the Wednesday evening that women would not be admitted.

The following morning the crowds gathered early. By 6 a.m. the court building was surrounded. Much to the annoyance of local people, admission was by ticket only. The crush was so great that it took almost half an hour for the officials and the judge, Chief Baron Alexander, to fight their way in. The weather was warm, and the court soon became uncomfortably hot.

There was no doubt that Maria had been murdered , but because of the decayed state of the body it was not possible to say how she had been killed. Cuts in the clothing suggested a stabbing: it was known that Corder had a short sword, and had had it sharpened. However, the cuts could have been caused when Mr Marten found the body with his mole-spud. The point was debated at length. Wounds to the head indicated that Maria had been shot. Corder's green handkerchief was fastened tightly round her neck, so strangulation could not be ruled out. Or perhaps the handkerchief had merely been used to drag the corpse across the barn floor. Maria could have been buried while still alive, and died of suffocation.

Since the exact cause of death could not be established beyond doubt, The Bill of Indictment, which comprised nine counts, was drawn up to cover all possible causes, singly and in combination. The Prosecution did not intend to let Corder escape on a technicality. The ninth count alone covers over two pages in Curtis. Curtis commented in a footnote that "This indictment is considered as a masterly specimen of legal skill and exactitude, and will, no doubt, become a standard for future reference." [Curtis, (p.111)]. It is said to have been used by Suffolk police for training cadets well into the 20th century.

Scanned copies of the indictments can be viewed as follows:

Even after the trial the exact means of Maria's death was under discussion, as the West Suffolk Coroner's letter to the Times of August 20th 1828 illustrates.

The trial lasted two days. The jury found Corder guilty. He was sentenced to be hanged and anatomised - i.e. the body was to be given to surgeons for medical research. Corder had more or less accepted that he would hang. He was devastated at the thought of being cut up.

Corder's Last Days

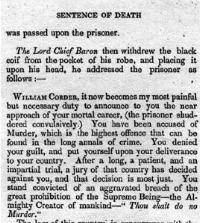

The judge, Chief Baron Alexander, passed sentence with the following words: |

Taken from Curtis's book |

"...My advice to you is, not to flatter yourself with the slightest hope of mercy on earth. You sent this unfortunate young woman to her account, with all her imperfections upon her head, without allowing her any time for preparation. She had not time to lift up her eyes to a throne of grace, to implore mercy and forgiveness for her manifold transgressions -she had no time allowed her to repent of her sins - no time granted to throw herself upon her knees, to implore pardon at the Eternal Throne! The same measure which you meted to her is not meted out to you again. A small interval is allowed you for preparation. Let me earnestly entreat you to use it well - the scene of this world closes upon you - but, I hope, another and a better world will open to your view. Remember the lessons of religion, which you, doubtless, received in your childhood - consider the effects which may be produced by a hearty and sincere repentance - listen to the voice of the ministers of religion who will, I trust, advise and console you, so that you may be able to meet with becoming resignation and fortitude that dreadful ordeal which you will have shortly to undergo. Nothing remains now for me to do but to pass upon you the awful sentence of the law, and that sentence is - That you be taken back to the prison from whence you came, and that you be taken from thence, on Monday next, to a place of Execution, and that you there be hanged by the Neck until you are Dead ; and that your body shall afterwards be dissected and anatomized ; and may the Lord God Almighty, of his infinite goodness, have mercy on your soul! " (Curtis p. 248) After the sentence was pronounced, Corder broke down, and was led sobbing from the bar. He may have been expecting an acquittal. Indeed, the women in his family, hopeful of his release, had ordered a chaise to take him home. He returned to the prison a condemned man. He had to change out of his own fashionable clothes into prison clothing and was moved from his "convenient apartment at the front of the prison" to a condemned cell. Even though suicide did not appeal to Corder (he said several times "Why should I destroy myself, and thus heap one sin upon another?") he was put under constant watch. In the 19th century it was thought that crimes committed in life would affect the progress of the eternal soul. Punishment was not regarded simply as retribution, but as a way for a criminal to gain divine forgiveness and redemption. However, as the Judge's words made clear, there was no hope of either without repentance. |

|

Before and during the trial, Corder had maintained his innocence. He was now encouraged - for the good of his soul - to confess his guilt. Over the next two days, John Orridge the Prison Governor, and the Reverend W. Stocking, the Prison Chaplain (whom Curtis described as "feelingly alive for the spiritual welfare of the prisoner") spent long hours with Corder, talking about the crime and the burden on his conscience. Corder spent the night after his trial in fitful sleep. He was woken at six the next morning by a visit from the Reverend Mr. Stocking who stayed for two hours. Corder worried about confessing, and the further disgrace and distress exposure of his lifetime's wrong-doings to public view would cause his family. Adding to their woes could be of no benefit to his soul. In a conversation with Orridge he said that confession to God was all that was necessary, that confession to man was Popedom or Popery and he would never do it. Even in extremis, Corder's secretive nature remained strong. The thought of anatomisation also preyed on his mind: while talking with Orridge about Maria's burial, he exclaimed "O, God! nobody will dig my grave!" On Saturday afternoon Corder's wife was allowed to visit for half an hour. Their meeting was tearful on both sides. Mrs. Corder, a woman of strong faith, urged her husband to repent and to prepare to account for himself before God. Her words had great effect, and he immersed himself in a religious book which she gave him. During the course of the day he attended the chapel. Mr. Stocking's discourse upon the Last Judgement made a deep impression. Stocking spent much of the day until late in the evening with Corder. The High Sheriff's chaplain, the Rev. Mr. Sheen also visited for half an hour, and in forcible language zealously exhorted the condemned man to repent and take refuge in the Gospel. While Corder was suffering these torments of conscience, work was afoot to prepare the scaffold. At Bury the scaffold was usually erected in the middle of a paddock on the NE side of the gaol. To reach it, condemned criminals were taken through the front door of the prison and along the road. The large crowd expected for Corder's execution would make this impossible. Instead, an opening , afterwards known as "Corder's Door," was made in the wall between the paddock and the gaol, and the scaffold erected next to it. Corder was informed of this arrangement. He appreciated that he would not have to pass through the yelling crowds. On Sunday morning Corder attended the service in the prison chapel. Mr. Orridge allowed the press to attend. After the other prisoners had taken their places and Mr. Stocking was ready, Corder was brought in and conducted by the Governor to the condemned pew. He sat in a posture he often adopted, holding a handkerchief to his face so that no-one could see his expression. He seemed to have become more religious. The service began with prayers written for such occasions. The Reverend Stocking stressed that divine forgiveness could only be won through repentance. He urged the condemned man to repent and spend his remaining hours in prayer, lest he suffer a worse punishment for eternity. It was no use putting off repentance until it was too late. Weeping, he implored God to enable Corder to repent his guilt. He then delivered the 'Condemned Sermon', discoursing on Luke xxii, v.41 "For we receive the due reward of our deeds." He described the state of heart, mind, and soul which a condemned prisoner should strive to reach, and how it should be manifested to others. His deportment should be exemplary and his repentence sincere, so that he might effect positive good and prevent much negative evil. He should try to make his peace with God. He should acknowledge the justice of his sentence. He should not be forced to repent, his repentance should not be superficial, but from the heart. The entire service was designed to bring home to Corder the awfulness of his situation. It appeared to have the desired effect. Corder was led back to his cell, barely ten metres from the chapel in extreme distress. He threw himself on the bed and sobbed convulsively for some time. By the afternoon Corder had recovered his composure. His wife was admitted for a final visit. She told him she would be happy if she knew that he had died a sincere penitent. Word was sent from his mother in Polstead, asking if he desired to see her one last time. He declined, concerned that it could be fatal for her health. Sending his dying love, he begged she would pray God to have mercy on him. Others who had known Corder pestered Orridge to allow them to visit. Asked if he would see a clergyman of his acquaintance, the prisoner refused, saying it would unnerve him and divert his attention from the calm reflection he needed. He added that he was quite content with the religious assistance of Mr Stocking. The good Reverend left him that evening, still exhorting him to repent. About nine o'clock on Sunday evening Mr. Orridge sent Corder a paper on confession, asking him to read it, and saying that he would call later to discuss it. After their earlier conversation about confession, the Governor had found a text which refuted Corder's ideas "Confess your faults one to another, and pray one for another." (James v. 16) . Orridge wrote that as one cannot hope to hide one's sins from God, this evidently meant 'confess your faults to one another, and pray for one another'. His argument continued that even if it were doubtful whether a man was bound to confess his errors to the world after offending society, there could be no doubt that he would not do anything wrong by confessing. When they talked later that evening, Orridge finally convinced Corder of the need for public confession. The Governor wrote it down, and Corder signed with a firm hand. He later also confessed to the forged cheque on Alexander & Co.'s Bank, but absolutely denied that he had stabbed Maria: he said that she had died from the pistol shot which had entered her right eye. Orridge stayed with until 1a.m. After he left, Corder talked with his companions about several topics: his crime, the justice of his condemnation, his childhood, how he had taken the wrong paths in life, and what he might have made of himself if he had made different choices. Reverend Stocking visited Corder again ealy on the morning of his execution and spent some time with him in private devotion. Corder then had a light breakfast and changed into his own clothes. He appeared to be calmer, acknowledged the justice of his sentence and prayed for forgiveness. At half-past nine he was taken to the chapel for the last time and seemed quite composed as he listened to the prayers and exhortations. The procedings included part of the burial service, at which Corder showed some emotion, and a prayer for those who were about to suffer execution. After the service. Corder returned to his cell with an unsteady step. Little more than an hour remained before his appointment with the hangman. A service of Holy Communion had been arranged for him. He joined in with a faltering voice, and afterwards appeared much refreshed. He next wrote a last letter to his wife, and then was taken to meet his fate.

"I am a surgeon, and live at Boxford. I was present when the body was viewed by the gentlemen of the jury, and made as minute an examination as I could. I first took off some pieces of sack which covered it; the body was lying upon its right side, with the head forced down upon the shoulder. There was an appearance of coagulated blood upon the cheek, and there appeared to be blood upon the clothes and handkerchiefs. The green handkerchief round the neck had been pulled tight, so that a man's hand might be put between the knot and the fold, and under it there was the appearance of a wound from a sharp instrument, but that part was so decomposed, I can only say that it had that appearance. The internal bone of the orbit of the right eye was fractured, as if a pointed instrument had been thrust into it, and the bone dividing the nose was displaced; the brain was in such a fluid state, that I am unable to say whether it had sustained any injury or not. Such a stab as I have described might have penetrated the brain. I found no injury in any other part; but there were two small portions of bone in the throat, which might have passed thither from the nose or orbit of the eye. I think the handkerchief was drawn tight enough to have caused death; the neck of the deceased appeared very much compressed indeed. The sack had evidently been tied after the deceased* had been put in head foremost. I had the mouth of the sack in my hand. *In a supplementary deposition since the exhumation of the body, the witness gives it as his decided opinion that a pistol ball entered the neck about the jugular vein, and proceeded, in an oblique direction, to the eye on the opposite side of the head, which would have produced the fracture before alluded to on the orbit. from Curtis, J. 'The Mysterious Murder of Maria Marten' pp. 29-30

Corder was given the chance to confess in court, but maintained he was innocent.

|

|

Some people still believe that he did not commit the murder, and was wrongly convicted. Documents in his own hand prepared for his trial (now in private possession) show that this was not so. At one point the text has been crossed out and the story changed: the original version exposed his guilt. At half-past eleven on the night before he was to hang, Corder at last confessed. He said that he and Maria had quarrelled about the burial of their child and other matters. A scuffle broke out, he took his pistol from his jacket pocket and fired. Maria fell dead. He denied utterly that he had stabbed her. However, it was felt by many that this was only a partial confession. Corder, true to his nature, kept the full story to himself to the very end. Several arguments have been put forward in Corder's defence:

|

| Go to Red Barn Homepage | Go to next topic - The execution |

Created 4 July 2001 by St Edmundsbury Museums Staff Last updated 27 December 2006 | Go to Main Home Page |