WHAT WAS A VILL?

By the end of the Anglo-Saxon period the country was divided into Shires or counties. Although there were a few towns, the local unit of administration seems to have been based on the "vill". The nearest modern equivalent is the civil parish, and it seems likely that some of these parishes equate to the similarly named medieval vill. Today we have an assumption that any one parish will contain a village of the same name as the parish. For example we see the town of Mildenhall seated within the parish of Mildenhall.

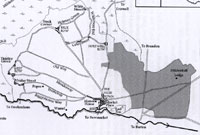

However, I suggest that in early medieval times a traveller would not expect to find any named settlements that we would recognise as a town, or even a village with the name of Mildenhall. It was understood that the vill of Mildenhall covered a certain area, and that it would contain a number of farmsteads, hamlets and settlements, each with its own name. If you refer to Sue Holden's map of Mildenhall illustrated here, you can see that even by the 15th century the vill contained several settlements named Rows, and several named Street, and the town which we nowadays see as Mildenhall, was then called High Town, not Mildenhall.

This view seems to me to illustrate that a vill which was known as Beodricsworth probably never referred to any one settlement, but to the area which was originally granted to one Beodric. Settlements and farmsteads within Beodricsworth probably each had its own local name, probably mainly referring to the name of its head man or head family. This idea is borne out by the early Anglo-Saxon boundary clause for the area granted to St Edmund, and by some wills relating to land.

In modern Bury we have evidence of several early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, so there were probably at least five small settlements within the area of today's town. One was probably where the Abbey's ruins remain today, one near Barons Road, one at Westgarth Gardens and one near Northumberland Avenue. A few skeletons were found in Tollgate Lane in the 19th century, and it seems likely that a further farmstead was located near the bottom of Tollgate Lane.

In the period from 946 to 951, Aelfgar, the Ealdorman of Essex, made his will. This will is catalogued by Professor Sawyer as S 1483. He intended to leave Cockfield to the infant religious establishment at Bury, but the form of words used is instructive. The sentence in Old English referring to Bedericesworth is as follows:

"And ■anne ouer vre aldre day ic an ■at lond at Cokefeld into Beodricheswrthe to seynt Eadmundes stowe." In other words St Edmund's Stow is clearly described as being located in Beodricheswrthe.

In the period between 942 and 951, Bishop Theodred of London made his will. This is recorded as reference S 1526 in the Sawyer catalogue of Anglo-Saxon charters. He left a number of bequests of land to his family and to various churches, including St Paul's in London.

This clause refers to land at Nowton, Horningsheath, Ickworth and Whepstead, Suffolk, to (be left to) St Edmund's church. Its location must have been well known, as it is not specified.

"And ic an ■at lond at Newetune and at HorninggeshŠthe and at Ikewrthe and at Wepstede into sancte Eadmundes kirke ■en Godes hewen to are for Ůeodred bisscopes soule."

Aethelflaed herself made a will between 962 and 991, but probably after 975. This will survives as Sawyer Reference S 1494.

Many of her lands were left to her sister for life, and then to a religious institution after her sister's death. These lands included the following clauses which benefitted the monastery at Bury St Edmunds:

" And I grant the two estates, Cockfield and Chelsworth, to the Ealdorman Brihtnoth and my sister for her life; and after her death to St Edmund's foundation at Bedericesworth."

The Old English original is as follows: "7 ic gean ■ara twegra landa Št CohhanfeldŠa 7 Št CŠorlesweor■e BŠorhtnoŠ Šaldormen. 7 mirŠ swuster hire dŠg. 7 ofer hire dŠg into sanctŠ Eadmundes stowe to Bydericeswyre. "

THE OTHER SECTIONS AND MAPS

The remaining sections

- "Local activity before the Romans Came",

- "The Roman Period followed by the Anglo-Saxons and Danes up to 1066", and

- "The Normans after 1066",

are all extracted from the main Chronicle. Those of you who have already read the Chronicle may care to skip these sections. Others may find these sections to be a handy aide memoire to those ideas relevant to the beginnings and the growth of Bury St Edmunds.

Similarly the Map section contains an extract of maps elsewhere on this website.

PH.D THESIS - "BUILDING MEDIEVAL BURY ST EDMUNDS" by ABBY L. ANTROBUS

The main item not available elsewhere on this website is the Ph.D thesis created by Abby Antrobus for her doctorate from the University of Durham in 2009. This exciting and comprehensive document contains in PDF form a mass of original research material, her own maps and diagrams, and photographs of features of medieval Bury St Edmunds.

Please give yourself plenty of time to look through the two volumes to gain a new view of early Bury. Volume two contains all the maps, figures and diagrams supporting the text in Volume one.